Abstract

Endometriosis is a complex, multi-faceted disease that extends far beyond its primary symptom of chronic pelvic pain, impacting reproductive health, mental well-being, and overall quality of life. Characterized by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, this condition manifests in a variety of forms, ranging from subtle, asymptomatic cases to those marked by debilitating pain, infertility, and organ dysfunction. Despite its high prevalence—affecting approximately 10% of individuals of reproductive age—endometriosis remains a poorly understood condition with an elusive etiology. While theories such as retrograde menstruation, immune dysregulation, and genetic predisposition provide partial explanations, the full range of contributing factors remains unclear. The disease's varied presentation, combined with the lack of a definitive diagnostic test, often results in delays in diagnosis, leading to prolonged suffering and uncertainty for many patients. Current treatment approaches—ranging from pharmacologic interventions to surgical procedures—focus primarily on symptom management rather than curative therapies, highlighting the critical need for more effective and targeted strategies. Furthermore, the psychological toll of living with chronic pain and fertility challenges associated with endometriosis exacerbates its social and emotional burden, making comprehensive care and patient support imperative. This paper seeks to explore the pathophysiology, diagnostic challenges, and evolving treatment paradigms of endometriosis, with an emphasis on the urgent need for improved awareness, early diagnosis, and innovative research to address the unmet needs of those affected.

Keywords

Endometriosis, menstruation, infertility, pain, uterus.

Introduction

Endometriosis is a habitual, frequently painful, and complex gynecological condition characterized by the presence of endometrial- suchlike tissue — tissue typically found inside the uterus — growing outside the uterine cavity. This ectopic tissue can be set up on the ovaries, fallopian tubes, pelvic peritoneum, and, in some cases, distant organs similar as the lungs, diaphragm, and intestines [1 - 4]. The condition affects an estimated 10- 15 of women of reproductive age worldwide, though it remains underdiagnosed due to its miscellaneous clinical donation and the invasive nature of its definitive diagnosis, which requires laparoscopic surgery. The pathogenesis of endometriosis remains inadequately understood, though several theses have been proposed [5 - 6]. These include retrograde menstruation, in which menstrual blood containing endometrial cells flows backward into the fallopian tubes and pelvic cavity, as well as vulnerable dysfunction, inheritable predilection, and environmental factors similar as exposure to endocrine disruptors [7 - 10]. Despite expansive exploration, no single cause has been linked, and it's likely that endometriosis results from the interplay of inheritable, epigenetic, and environmental factors. Endometriosis can lead to a wide range of symptoms, the most common being pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea( painful period), dyspareunia( pain during intercourse), and infertility. The inflexibility of symptoms doesn't always relate with the extent of the condition, and some women with significant endometrial implants may witness many symptoms, while others with minimum lesions may suffer from enervating pain [11 - 13]. This distinction in symptom presentation makes the clinical operation of endometriosis particularly grueling , as it's delicate to predict the progression or inflexibility of the condition grounded on imaging studies alone. Infertility is another major concern for women with endometriosis, with studies indicating that roughly 30- 50 of women with the condition may witness difficulties conceiving [14, 15]. The underpinning mechanisms contributing to infertility in endometriosis are multifactorial and may include anatomical deformations due to adhesions, altered ovarian function, bloodied embryo implantation, and differences in the peritoneal atmosphere. Assisted reproductive technologies( ART), similar as in vitro fertilization( IVF), may be indicated for women with severe infertility due to endometriosis, though the success rates for ART in these cases are lower than for women without the condition [16 – 18]. The opinion of endometriosis is frequently delayed, with cases generally passing symptoms for times before a opinion is made. Non-invasive individual tools similar as pelvic ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging( MRI) may help identify endometriotic cysts( endometriomas) or deep insinuating endometriosis( DIE), but the gold standard for opinion remains laparoscopy, which allows for direct visualization of lesions, vivisection, and histopathological evidence [19, 20] . Still, numerous women remain undiagnosed, and the condition is frequently misattributed to other causes of pelvic pain. The operation of endometriosis involves a multidisciplinary approach that can include pharmacologic curatives, surgery, and life variations. First- line treatment frequently consists of hormonal curatives designed to suppress ovarian estrogen product, which in turn reduces the proliferation of ectopic endometrial tissue [21, 22] . These treatments may include combined oral contraceptives, progestins, GnRH agonists, and hormonal IUDs. For women with severe symptoms, surgical intervention may be necessary, particularly to remove large excrescencies or deeply infiltrative lesions [23 - 25]. Conservative surgical ways aim to save fertility, but in some cases, further radical procedures, similar as hysterectomy, may be indicated when fertility isn't a concern[26, 27]. Still, indeed with treatment, rush rates are high, with studies showing that over to 50 of women experience symptom rush within five times after surgery. This has led to a growing interest in spare curatives, similar as the use of anti-inflammatory agents, antioxidants, and salutary interventions, as well as research into new pharmacological treatments targeting the molecular pathways involved in the complaint, including seditious cytokines, growth factors, and vulnerable modulation [28,29] . Cerebral torture, including anxiety and depression, is common among women with endometriosis, due to the habitual pain, gravidity enterprises, and the societal smirch associated with reproductive health issues[30, 31] . Addressing the cerebral aspects of the condition is a critical element of comprehensive care, with probative curatives, comforting, and pain operation strategies playing an important part in perfecting overall quality of life. Endometriosis is decreasingly honored as not just a original pelvic complaint but a systemic condition, with arising substantiation suggesting its association with other conditions similar as autoimmune diseases, perverse bowel pattern, and indeed certain cancers [32, 33] . Ongoing exploration is exploring the molecular and inheritable underpinnings of endometriosis to more understand its pathogenesis and identify implicit biomarkers for earlier opinion, more effective treatments, and preventative strategies. In conclusion, endometriosis is a enervating condition that significantly impacts the lives of affected women. Although advances in individual ways and remedial interventions have been made, challenges remain in furnishing timely opinion and substantiated treatment. Given its multifaceted nature and the lack of a cure, continued exploration into the causes, mechanisms, and operation strategies for endometriosis is critical to perfecting patient issues and quality of life [34- 36] .

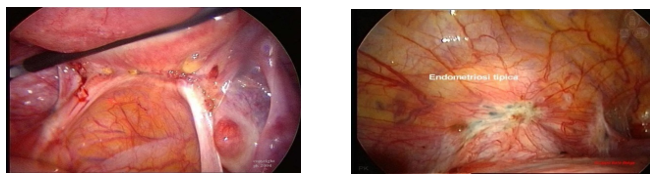

Fig. 1 - Endometriosis is when tissue similar to your uterine lining is inside your pelvis or abdomen. It can cause painful and heavy periods, pelvic pain and make it hard to get pregnant.

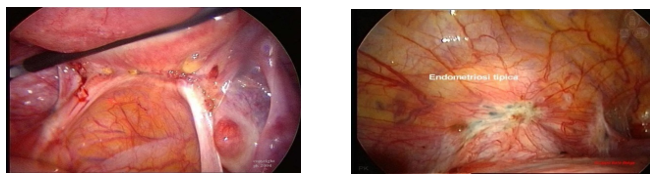

Fig. 2 – Microscopy of endometriosis.

Etiology :

The exact etiology of endometriosis remains incompletely understood, with no single cause identified, but rather, it is believed to arise from a multifactorial interplay of genetic, hormonal, immune, and environmental factors. One of the most widely accepted explanations is the retrograde menstruation theory, first proposed by Dr. John Sampson in the 1920s, which suggests that during menstruation, endometrial cells from the uterine lining flow backward through the fallopian tubes into the pelvic cavity, where they implant and proliferate on the peritoneal surface or other pelvic organs [37- 39] . However, retrograde menstruation alone is insufficient to explain the condition, as this process occurs in many individuals without the development of endometriosis. Another plausible explanation is coelomic metaplasia, which posits that the cells lining the pelvic cavity may undergo transformation into endometrial-like tissue in response to hormonal imbalances or inflammatory stimuli, leading to ectopic growth [40- 42]. Genetic factors also play a crucial role, with studies showing a higher risk in individuals with a family history of endometriosis, suggesting a hereditary component. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are actively exploring specific genetic loci that might predispose individuals to this condition. Additionally, immune system dysregulation has been implicated, as individuals with endometriosis often exhibit abnormal immune responses, including altered T-cell function and elevated pro-inflammatory cytokine levels, which could allow ectopic endometrial cells to evade the immune system and sustain their growth. Other theories include lymphatic or hematogenous spread, where endometrial cells may disseminate through the bloodstream or lymphatic system to distant sites, such as the lungs or brain, explaining cases of extrapelvic endometriosis [43 - 45] . Environmental factors, particularly endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) such as bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates, have also been linked to increased risk, as these substances can mimic or interfere with estrogen signaling, a key driver of endometrial tissue growth. The embryonic development theory suggests that endometrial tissue may be incorrectly placed during fetal development, leading to endometriosis later in life. Other theories, such as the stem cell theory, propose that circulating stem cells from bone marrow may migrate to the pelvic cavity and transform into endometrial-like cells, while surgical trauma or scarring has also been suggested as a potential cause for localized endometriosis [46- 48] . Despite significant advances in research, the precise mechanisms behind endometriosis remain unclear, and ongoing exploration of genetic, immunological, and environmental factors is essential to develop more effective diagnostic and therapeutic approaches [ 49 -51] .

Table 1- Etiology of Endometriosis: A Complex Interplay of Factors

|

Factor

|

Explanation

|

|

Retrograde Menstruation

|

Endometrial cells flow backward through the fallopian tubes during menstruation and implant outside the uterus.

|

|

Coelomic Metaplasia

|

Pelvic cavity cells transform into endometrial-like tissue due to hormonal imbalances or inflammation.

|

|

Genetic Predisposition

|

Family history of endometriosis suggests a genetic component. GWAS studies are exploring specific loci.

|

|

Immune System Dysregulation

|

Abnormal immune responses allow ectopic endometrial cells to grow.

|

|

Lymphatic or Hematogenous Spread

|

Endometrial cells spread through the bloodstream or lymphatic system to distant sites.

|

|

Environmental Factors

|

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) can mimic or interfere with estrogen signaling.

|

|

Embryonic Development

|

Endometrial tissue may be incorrectly placed during fetal development.

|

|

Stem Cell Theory

|

Circulating stem cells may transform into endometrial-like cells in the pelvic cavity.

|

|

Surgical Trauma or Scarring

|

Localized endometriosis may result from previous pelvic surgery.

|

Clinical Sign & Symptoms:

Endometriosis is a complex, heterogeneous disease with a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations that vary significantly in terms of severity, timing, and presentation, depending on the location, extent, and depth of ectopic endometrial tissue [52 - 54] . While some individuals may exhibit subtle symptoms, others may experience debilitating effects that significantly impair quality of life. The most prominent and hallmark symptom of endometriosis is chronic pelvic pain, which is typically cyclic and often exacerbated during menstruation (dysmenorrhea). This pain results from the inflammatory response elicited by endometrial-like tissue that has implanted outside the uterine cavity, where it continues to respond to the hormonal fluctuations of the menstrual cycle. The pain is often described as crampy, sharp, or dull, and may radiate to adjacent regions, including the lower back, thighs, and even the gastrointestinal tract. The intensity and timing of pelvic pain can vary, often occurring before and during menstruation, as well as during ovulation and sometimes with sexual intercourse [55-58] . Dyspareunia (painful intercourse) is another key clinical manifestation of endometriosis, arising due to the presence of endometrial tissue located on or near the pelvic organs such as the ovaries, rectum, or vaginal cuff. The pain associated with dyspareunia is typically deep and may worsen after intercourse, limiting sexual activity and contributing to emotional distress, social isolation, and reduced quality of life [59-61] . Infertility is another major clinical consequence of endometriosis, affecting approximately 30-50% of individuals with the condition. The presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterus can lead to anatomical distortions, adhesions, or obstruction of the fallopian tubes, thereby hindering natural conception. Additionally, ovarian function may be impaired due to the inflammatory environment, and in vitro fertilization (IVF) success rates may be reduced in affected individuals, requiring additional medical intervention or surgical procedures to improve fertility outcomes [62-65] . Endometriosis also frequently presents with a range of gastrointestinal symptoms, including abdominal bloating, constipation, diarrhea, nausea, and painful bowel movements, often exacerbated during menstruation [66,67] . These symptoms can be mistaken for other gastrointestinal disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), making it challenging to differentiate between the two conditions. Painful bowel movements, particularly when associated with menstruation, occur when endometrial lesions are localized to the rectum, sigmoid colon, or other regions of the gastrointestinal tract, contributing to significant discomfort [68,69] . In some cases, urinary symptoms may also manifest when endometrial tissue infiltrates areas such as the bladder or ureters. Symptoms may include dysuria (painful urination), urinary frequency or urgency, and hematuria (blood in the urine), which are often aggravated during menstruation. Systemic manifestations of endometriosis, such as chronic fatigue, are also common and are thought to result from the combined effects of chronic pain, sleep disturbances, anemia (secondary to heavy menstrual bleeding), and systemic inflammation. Fatigue in endometriosis is often described as persistent and debilitating, further compounding the difficulty in managing the disease [70-73] . Lower back pain is another symptom frequently reported by individuals with endometriosis. This pain, often associated with endometrial implants affecting the pelvic ligaments, rectum, or other pelvic organs, can radiate to the lower extremities and mimic other forms of musculoskeletal pain, such as sciatica.In advanced cases of endometriosis, adhesions (fibrous bands of scar tissue) may form as a consequence of chronic inflammation and bleeding from ectopic endometrial tissue. Adhesions can bind organs together, restrict organ mobility, and lead to organ dysfunction, including bowel obstruction, urinary retention, and infertility [74-77] . In severe cases, organ dysfunction may require surgical intervention to release adhesions and restore organ function. However, some individuals with endometriosis may remain asymptomatic, particularly when the ectopic endometrial lesions are small or localized to areas that do not trigger significant symptoms. Asymptomatic cases can still pose long-term reproductive challenges, including difficulties with conception or suboptimal IVF outcomes, making early detection critical. Moreover, endometriosis can be associated with a variety of non-specific symptoms, such as headaches, menstrual irregularities (e.g., prolonged or heavy bleeding), and rectal bleeding, particularly when lesions affect the gastrointestinal tract. The presence of these non-specific symptoms further complicates diagnosis, as they overlap with conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), interstitial cystitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), leading to potential delays in obtaining a definitive diagnosis [78-81] . The clinical presentation of endometriosis is often protean, with symptoms that may evolve over time, depending on the progression of the disease. Given the diversity of symptoms, many of which mimic other conditions, timely diagnosis and management are crucial for minimizing disease impact and optimizing outcomes.In summary, the clinical manifestations of endometriosis span a wide range of systems, including reproductive, gastrointestinal, and urinary systems, with varying degrees of severity. The overlapping symptoms with other common conditions, such as IBS and PID, can complicate diagnosis, making a thorough clinical evaluation essential. Due to the significant impact of the disease on the physical, emotional, and psychological well-being of individuals, a comprehensive understanding of its clinical presentation is crucial for timely diagnosis, intervention, and effective management strategies [82- 83] .

Fig 2 – Various symptoms of endometriosis.

Clinical diagnosis of endometriosis :

The diagnosis of endometriosis is often challenging due to its diverse clinical presentations and the overlap of symptoms with other conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), or functional gastrointestinal disorders. There is no single diagnostic test for endometriosis, and the diagnostic process typically involves a combination of clinical evaluation, imaging studies, and, in some cases, surgical intervention. Initial diagnosis begins with a thorough clinical history and physical examination, focusing on common symptoms such as chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea (painful menstruation), dyspareunia (painful intercourse), and infertility [84-86] . While physical examination may reveal tenderness or nodularity in the pelvic region, it is not conclusive, especially in cases where endometrial lesions are small or deeply infiltrating. Imaging techniques are often employed to aid in diagnosis, with transvaginal ultrasound being commonly used as an initial screening tool to detect large ovarian endometriomas, although it is less effective for smaller lesions or deep infiltrations. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is increasingly utilized to provide detailed imaging of the pelvic organs and detect deep infiltrating endometriosis, but it may have reduced sensitivity for small or superficial lesions. In more complex cases, computed tomography (CT) may be used to assess for extrapelvic endometriosis or complications such as bowel obstruction. However, the gold standard for diagnosing endometriosis remains laparoscopy, a minimally invasive surgical procedure that allows direct visualization of the pelvic cavity, enabling identification of endometrial implants, adhesions, or ovarian cysts. During laparoscopy, a biopsy of the suspected lesions is often performed, and histopathological examination of the tissue is required to confirm the diagnosis, with characteristic findings including glands, stroma, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages [87- 90] . While non-invasive biomarkers like CA-125 (Cancer Antigen 125) are being studied as potential diagnostic tools, their sensitivity and specificity are limited, and they are typically not used as standalone tests but rather in conjunction with other diagnostic methods. Differential diagnosis includes conditions with similar symptoms, such as PID, IBS, interstitial cystitis, ovarian cysts, and uterine fibroids, all of which must be ruled out to confirm endometriosis. Although ultrasound and MRI are useful for detecting larger lesions or deep infiltrating endometriosis, laparoscopy remains the most definitive and reliable diagnostic method. The diagnosis of endometriosis is often delayed due to the nonspecific nature of its symptoms and the overlap with other conditions, emphasizing the need for a multidisciplinary approach that integrates clinical evaluation, imaging studies, and surgical intervention. Ongoing research into non-invasive diagnostic biomarkers holds promise for more efficient detection methods in the future [91-94] .

Treatment of endometriosis:

The treatment of endometriosis is complex and highly individualized, aiming to alleviate pain, manage symptoms, and enhance quality of life, particularly when infertility is a concern. The first line of treatment typically involves pharmacological interventions designed to control pain and hormonal activity. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used to manage pain and inflammation, providing immediate relief, while hormonal therapies aim to suppress the growth of endometrial-like tissue. Birth control pills, hormone patches, and vaginal rings, often combined with progestin-only options like pills or

Fig. 3 – Treatment using different methods.

injections (such as Depo-Provera), work to regulate menstrual cycles and minimize the hormonal fluctuations that trigger endometrial growth [95-98] . Additionally, a hormonal intrauterine device (IUD), such as Mirena, delivers localized progestin to reduce or stop menstruation and alleviate pain. For more severe cases, GnRH agonists (e.g., Lupron) and aromatase inhibitors (e.g., Letrozole) may be used to lower estrogen levels, effectively inducing a temporary menopausal state and halting endometrial tissue proliferation, though these treatments can come with side effects like bone loss and mood swings, requiring careful management [99-102] . Surgical options become relevant in cases where medications fail or symptoms are debilitating. Laparoscopy, a minimally invasive surgery, is often employed to remove or destroy the ectopic endometrial lesions and adhesions, with the added benefit of improving fertility in some cases. In more severe instances, particularly for patients who no longer wish to preserve fertility, a hysterectomy—removal of the uterus—and sometimes oophorectomy, removal of the ovaries, may be recommended, though this is generally seen as a last resort. Fertility-preserving treatments may include assisted reproductive technologies (ART), such as in vitro fertilization (IVF) and ovarian stimulation therapies, which help bypass the impact of endometriosis on the reproductive organs [103- 106] . Alongside medical and surgical interventions, lifestyle modifications play a significant role in managing endometriosis. Dietary adjustments—such as adopting an anti-inflammatory diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, and fiber—can sometimes provide symptom relief, as can regular exercise, which helps reduce inflammation and improve mood. Stress management techniques, including yoga and meditation, are also beneficial for pain management and emotional well-being. Physical therapy, particularly pelvic floor therapy, is increasingly recommended to address muscular tension and pelvic pain associated with the condition, and some patients turn to acupuncture as an alternative therapy to alleviate symptoms. Though evidence is mixed, complementary therapies like herbal supplements (e.g., turmeric, omega-3 fatty acids) are sometimes used, but these should be approached cautiously and under the guidance of a healthcare provider due to potential interactions with conventional treatments. Emotional and psychological support are also crucial aspects of managing endometriosis, as the chronic pain and fertility struggles can lead to anxiety, depression, and feelings of isolation. Support groups and counseling can offer valuable coping strategies. Ultimately, the optimal treatment strategy for endometriosis often requires a combination of approaches tailored to each patient’s specific symptoms, severity of the condition, reproductive goals, and overall health, in close collaboration with a multidisciplinary healthcare team, typically led by a gynecologist or reproductive specialist [107- 111] .

Table 2: Table that encapsulates the key elements of endometriosis treatment, including pharmacological, surgical, and lifestyle interventions.

|

Treatment Category

|

Intervention

|

Mechanism of Action

|

Indications /Usage

|

Potential Side Effects

|

|

Pharmacological Treatments

|

NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen)

|

Inhibits COX enzymes, reducing pain and inflammation.

|

First-line pain relief and inflammation control.

|

Gastrointestinal issues, kidney impairment, cardiovascular risk.

|

|

Pharmacological Treatments

|

Hormonal therapies

|

Suppresses estrogen and progesterone, reducing endometrial tissue growth.

|

Controls disease progression, regulates menstrual cycles.

|

Nausea, weight gain, mood swings, blood clot risks.

|

|

Pharmacological Treatments

|

Birth control pills, patches, rings

|

Regulates hormonal fluctuations, suppresses ovulation.

|

Symptom management, menstrual regulation.

|

Headaches, nausea, blood clots.

|

|

Pharmacological Treatments

|

Progestin-only therapies

|

Suppresses ovulation and endometrial growth.

|

Used in severe cases, to reduce bleeding and pain.

|

Bone loss, irregular bleeding, mood changes.

|

|

Pharmacological Treatments

|

GnRH Agonists (e.g., Lupron)

|

Lowers estrogen to induce temporary menopause, halting endometrial proliferation.

|

Severe endometriosis cases, short-term suppression.

|

Bone density loss, hot flashes, mood swings.

|

|

Pharmacological Treatments

|

Aromatase inhibitors (e.g., Letrozole)

|

Reduces estrogen synthesis, slowing tissue growth.

|

Used with GnRH agonists or for recurrence.

|

Joint pain, fatigue, osteoporosis.

|

|

Surgical Treatments

|

Laparoscopy

|

Minimally invasive removal/destruction of lesions and adhesions.

|

Symptomatic relief, fertility improvement.

|

Infection, scarring, organ damage.

|

|

Surgical Treatments

|

Hysterectomy/Oophorectomy

|

Removal of uterus and/or ovaries to eliminate endometrial tissue.

|

Last resort for severe cases, fertility preservation not prioritized.

|

Menopausal symptoms, hormonal imbalances, surgical risks.

|

|

Fertility Preservation

|

In vitro fertilization (IVF)

|

Bypasses endometriosis-related reproductive issues by assisting fertilization.

|

Preserves fertility, aids conception.

|

Ovarian hyperstimulation, multiple pregnancies.

|

|

Fertility Preservation

|

Ovarian stimulation

|

Stimulates ovaries to produce multiple eggs for ART.

|

Optimizes fertility outcomes.

|

Hormonal imbalances, emotional burden.

|

|

Lifestyle Modifications

|

Anti-inflammatory diet

|

Reduces systemic inflammation, rich in omega-3s, antioxidants, and fiber.

|

Symptom control, reduces flare-ups.

|

Generally safe; balanced nutrition required.

|

|

Lifestyle Modifications

|

Exercise

|

Improves circulation, reduces inflammation, and enhances mood through endorphin release.

|

Adjunctive therapy for pain and mental health improvement.

|

Risk of overexertion or injury.

|

|

Lifestyle Modifications

|

Yoga/Meditation

|

Reduces stress, improves mental health, alleviates pain.

|

Pain relief, stress management, emotional well-being.

|

Aggravation if not tailored to individual conditions.

|

|

Lifestyle Modifications

|

Pelvic floor therapy

|

Targets pelvic muscles to alleviate pain and tension.

|

Manages pelvic pain and muscular tension.

|

Temporary discomfort or soreness.

|

|

Complementary Therapies

|

Acupuncture

|

Stimulates specific points to balance energy and reduce symptoms.

|

Pain relief, symptom management.

|

Mixed evidence; consult healthcare provider.

|

|

Complementary Therapies

|

Herbal supplements (e.g., turmeric)

|

Anti-inflammatory effects, sometimes used to complement pharmacological treatment.

|

Symptom relief.

|

Risk of drug interactions, lack of clinical evidence.

|

|

Psychological Support

|

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

|

Addresses anxiety, depression, and pain management through coping strategies.

|

Managing chronic pain and emotional distress.

|

Emotional discomfort during therapy.

|

|

Psychological Support

|

Support groups

|

Provides emotional and social support from peers with shared experiences.

|

Emotional resilience, coping strategies.

|

Possible negative reinforcement in some individuals.

|

Risk Factors of endometriosis

Endometriosis is a multifactorial condition with a range of risk factors that include genetic, hormonal, reproductive, environmental, and lifestyle influences. Family history plays a significant role, as women with a first-degree relative (such as a mother or sister) diagnosed with endometriosis are at a significantly higher risk, pointing to a potential genetic predisposition. Specific genetic factors, including mutations in certain genes related to immune response and hormonal regulation, have been identified, though they are still not fully understood. Hormonal factors are also central to the development of endometriosis; the condition is estrogen-dependent, and higher levels or prolonged exposure to estrogen, which stimulates the growth of endometrial tissue, are thought to play a role [112-115] . Women who begin menstruating at an early age (early menarche), experience long menstrual cycles with heavy or prolonged periods, or have shorter cycles with higher estrogen production, are believed to be at a higher risk. Furthermore, women who are nulliparous (have never been pregnant) or delay childbirth into their late 20s or 30s may also face increased risk [116,117] . Pregnancy and breastfeeding can offer some protection, as they suppress ovulation and reduce menstrual flow, which in turn lowers the chances of retrograde menstruation—a process where menstrual blood flows backward into the pelvic cavity, potentially contributing to the growth of endometrial tissue outside the uterus. Retrograde menstruation, combined with anatomical factors like pelvic or uterine abnormalities, such as a narrow cervix or vaginal obstruction, may increase the likelihood of endometrial cells implanting and growing outside the uterus [118-121] . In addition to hormonal and anatomical factors, environmental influences like exposure to endocrine disruptors—chemicals found in everyday items such as plastics, pesticides, and household cleaning products—are thought to increase the risk of endometriosis by interfering with hormone regulation. Chemicals like bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates, which mimic estrogen, are especially concerning for their potential role in the development of the condition. Environmental pollutants and toxins, combined with lifestyle factors such as obesity and physical inactivity, may also play a role. Obesity is associated with higher levels of estrogen, which may stimulate the growth of endometriosis, while lack of exercise can contribute to hormone imbalances and weight gain, further increasing risk [122-125] . Additionally, chronic stress has been suggested as a potential risk factor, as stress can influence hormone levels, increase inflammation, and exacerbate symptoms in those already living with endometriosis. Women with autoimmune diseases, such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and Crohn’s disease, are also more likely to develop endometriosis, potentially due to immune system dysregulation that allows endometrial cells to grow outside the uterus [126- 128] . Although autoimmune disease and endometriosis share some overlapping symptoms and immune system dysfunction, the precise mechanisms remain under investigation. Other reproductive factors, such as previous pelvic infections or surgical procedures (like cesarean sections or laparoscopies), may also raise the risk by causing scarring or inflammation in the pelvic region, which can facilitate the implantation of endometrial cells. The interplay of these diverse risk factors means that endometriosis likely results from a complex combination of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle influences, with no single cause, and the condition can occur even in women who do not fit any of the common risk profiles. Despite these associations, much about the precise causes of endometriosis remains elusive, and more research is needed to better understand how these factors interact and contribute to the development of the condition [129-132] .

Research and Future directions

Research into endometriosis is rapidly evolving, driven by the urgent need for a more comprehensive understanding of its underlying causes, the development of improved diagnostic methods, and the discovery of more effective, less invasive treatments. Despite being a complex and often misunderstood condition, significant progress is being made across several promising areas of research. One of the primary focuses is understanding the pathophysiology of the disease, particularly its molecular and genetic underpinnings. Although family history is recognized as a risk factor, the specific genes implicated in endometriosis are not fully understood, and research is concentrating on identifying genetic markers and susceptibility genes, particularly those associated with immune function, inflammation, and estrogen signaling. This work may eventually lead to personalized medicine approaches, tailoring treatments to an individual's genetic profile. Additionally, research into immune system dysfunction is gaining momentum, as studies suggest that in women with endometriosis, the immune system fails to recognize and eliminate endometrial tissue that grows outside the uterus, resulting in chronic inflammation and the formation of endometrial implants [133-137] . Investigations are examining the role of immune cells such as macrophages and T-cells, along with the contribution of cytokines and other immune mediators to the persistence of the condition. Furthermore, epigenetics—the study of changes in gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence—has emerged as a key area, with researchers exploring how environmental factors such as toxins and hormonal exposures may cause epigenetic modifications that promote the growth of endometrial tissue outside the uterus [138-141] . In parallel, efforts to improve early detection are intensifying, given that endometriosis is often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed due to its diverse symptoms. Current diagnostic methods like laparoscopy are invasive and expensive, prompting research into non-invasive diagnostic tests using biomarkers in blood, urine, or menstrual fluid. Emerging biomarkers such as CA-125 and miRNAs are being investigated for their potential to offer earlier, less invasive detection methods [142-145] . Advances in imaging technologies, such as MRI and ultrasound, are also being explored to enhance the sensitivity and specificity of detecting endometriosis, especially in identifying smaller or deep lesions, and researchers are examining the potential of AI and machine learning to assist in analyzing complex data and predicting the risk of endometriosis. A significant area of research focuses on the relationship between endometriosis and fertility, as many women with endometriosis face infertility challenges. Studies are investigating how endometriosis impairs fertility at the molecular level, including the impact on ovarian reserve, oocyte quality, fallopian tube function, and endometrial receptivity [146-149] . Fertility preservation techniques such as egg freezing, embryo cryopreservation, and IVF are being researched for women with severe endometriosis, with studies evaluating how these approaches may enhance pregnancy outcomes. Additionally, clinical trials are assessing the impact of treatments like GnRH analogs, aromatase inhibitors, and progestins on fertility outcomes, seeking to guide fertility-sparing decisions [150- 152] . In the realm of treatment options, there is a strong push to develop pharmacological advances that address both the pain and progression of the disease, as existing treatments often come with significant side effects. Targeted therapies that aim to precisely modulate the molecular mechanisms driving endometriosis, such as inflammation, hormonal dysregulation, and immune dysfunction, are under investigation. Researchers are also focusing on pain management, given that chronic pelvic pain is one of the most debilitating symptoms of endometriosis [153- 155] . Studies are exploring novel approaches, including neurostimulation devices and new pharmacological interventions, to better manage the pain and improve quality of life. Another emerging field of research is the microbiome, particularly the endometrial microbiome, with researchers studying how the community of microbes within the reproductive tract might influence the development or progression of endometriosis. Alterations in the gut microbiome are also being explored, as many women with endometriosis report gastrointestinal symptoms [156-158] . Investigating the gut-brain-endometrium axis could offer valuable insights into how changes in gut bacteria may affect endometriosis. Additionally, the potential link between endometriosis and ovarian cancer, particularly endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer (EAOC), is becoming a significant area of focus, with research exploring how chronic inflammation and abnormal cell growth in endometrial tissue may elevate cancer risk. Recognizing the psychosocial impact of endometriosis, research is also delving into the mental health challenges associated with the condition, including anxiety, depression, and reduced quality of life [159-161] . Multidisciplinary approaches involving gynecologists, pain specialists, psychologists, and dietitians are being explored to provide comprehensive care for patients. Another important focus is early detection in adolescents, as many young women suffer from endometriosis-related symptoms that go unrecognized. Studies are investigating how early intervention can improve long-term outcomes, particularly regarding fertility preservation and quality of life. Furthermore, global and sociological research is being conducted to address healthcare disparities, as endometriosis remains underdiagnosed in many regions, especially in low- and middle-income countries [162-163] . Research is exploring how socioeconomic status, cultural factors, and healthcare infrastructure can influence the diagnosis and management of the disease. Finally, the integration of multidisciplinary care models is gaining traction, with researchers exploring how collaborative approaches can better address the complex, multi-system impacts of endometriosis and improve patient outcomes. Collectively, these areas of research are driving significant progress in understanding the causes, improving the diagnosis, and developing more effective treatments for endometriosis, ultimately aiming to improve the quality of life for those affected by this challenging condition [164-166] .

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, endometriosis remains a profoundly multifaceted and enigmatic condition that continues to present significant challenges to both patients and clinicians alike. Characterized by the growth of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, this disorder disrupts not only the physical but also the emotional and reproductive health of those affected. Its wide-ranging symptoms, from chronic pelvic pain to infertility and gastrointestinal distress, make it a particularly complex condition to manage, often leading to delayed diagnoses and inadequate treatment. The profound and pervasive impact of endometriosis underscores the urgent need for a deeper, more comprehensive understanding of its pathophysiology and the development of more personalized, patient-centered care approaches. As scientific inquiry increasingly focuses on the intricate genetic, immune, and epigenetic mechanisms underlying the development and progression of endometriosis, significant strides are being made toward elucidating its complex etiology. Researchers are beginning to uncover critical molecular pathways, including those involved in immune dysfunction, estrogen signaling, and inflammation, all of which contribute to the persistence of ectopic endometrial tissue and its associated symptoms. Such breakthroughs are paving the way for the development of more targeted, effective treatments that go beyond the traditional hormonal therapies and invasive surgeries currently available. In particular, advancements in non-invasive diagnostic methods, such as blood-based biomarkers, miRNA profiling, and improved imaging techniques, promise to revolutionize early detection, reducing the reliance on costly and invasive procedures like laparoscopy. Additionally, innovations in fertility preservation and pain management, including new pharmacological agents and neurostimulation therapies, offer hope for improving both the reproductive and quality-of-life outcomes for women living with this debilitating condition. However, it is equally critical that, alongside these scientific advancements, we address the broader sociocultural and healthcare disparities surrounding endometriosis. Many women, particularly those in low- and middle-income countries or from marginalized communities, continue to experience challenges in accessing timely diagnosis, adequate care, and support services. Furthermore, the stigma associated with menstruation and reproductive health often leads to the minimization of symptoms, contributing to significant delays in diagnosis and treatment. As such, efforts to enhance public awareness, improve healthcare infrastructure, and promote equitable access to care are essential for ensuring that women everywhere receive the compassionate, timely, and comprehensive care they deserve. Ultimately, the ongoing pursuit of knowledge in endometriosis research is not merely a scientific endeavor but a societal commitment to improving the lives of millions of women worldwide. It represents the hope of a future where this often-silent and under-recognized condition no longer dictates a woman's ability to lead a fulfilling, healthy life. With continued investment in research, education, and healthcare reform, there is potential for a future in which endometriosis is not just better understood and managed but also eradicated as a source of suffering and limitation.

REFERENCES

- Woodward PJ, Sohaey R, Mezzetti Jr TP. Endometriosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2001 Jan;21(1):193-216.

- Clement PB. Diseases of the peritoneum. InBlaustein’s pathology of the female genital tract 1994 (pp. 647-703). New York, NY: Springer New York.

- Monga A, Dobbs SP. Gynaecology by ten teachers. CRC Press; 2011 Mar 25.

- Magowan BA, Owen P, Drife J. Clinical obstetrics and gynaecology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2009 Aug 1.

- Taylor HS, Kotlyar AM, Flores VA. Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations. The Lancet. 2021 Feb 27;397(10276):839-52.

- Smolarz B, Szy??o K, Romanowicz H. Endometriosis: epidemiology, classification, pathogenesis, treatment and genetics (review of literature). International journal of molecular sciences. 2021 Sep 29;22(19):10554.

- Foster RA. Male genital system. Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals: Volume 3. 2016:465.

- Kustritz MV. Clinical canine and feline reproduction: evidence-based answers. John Wiley & Sons; 2011 Nov 16.

- Kleinman RE, Goulet OJ, Mieli-Vergani G, Sanderson IR, Sherman PM, Shneider BL, editors. Walker's pediatric gastrointestinal disease: physiology, diagnosis, management. PMPH USA, Ltd; 2018 Jun 4.

- Andersen BL, editor. Women with cancer: Psychological perspectives. Springer Science & Business Media; 2012 Dec 6.

- Zubrzycka A, Zubrzycki M, Janecka A, Zubrzycka M. New Horizons in the Etiopathogenesis and Non-Invasive Diagnosis of Endometriosis. Current molecular medicine. 2015 Sep 1;15(8):697-713.

- Fan P, Li T. Unveil the pain of endometriosis: from the perspective of the nervous system. Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine. 2022 Jan;24:e36.

- McCallion A, Sisnett DJ, Zutautas KB, Hayati D, Spiess KG, Aleksieva S, Lingegowda H, Koti M, Tayade C. Endometriosis through an immunological lens: a pathophysiology based in immune dysregulation. Exploration of Immunology. 2022 Jul 26;2(4):454-83.

- Spaczynski RZ, Duleba AJ. Diagnosis of endometriosis. InSeminars in reproductive medicine 2003 (Vol. 21, No. 02, pp. 193-208). Copyright© 2003 by Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., 333 Seventh Avenue, New York, NY 10001, USA. Tel.:+ 1 (212) 584-4662.

- Olive DL, Lee KL. Analysis of sequential treatment protocols for endometriosis-associated infertility. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1986 Mar 1;154(3):613-9.

- Morel MC. Equine reproductive physiology, breeding and stud management. CABI; 2020 Nov 2.

- Reynard J, Brewster S, Biers S. Oxford handbook of urology. OUP Oxford; 2013 Feb 28.

- McCalman J. Sex and Suffering. Melbourne Univ. Publishing; 2012 Nov 27.

- Bazot M, Lafont C, Rouzier R, Roseau G, Thomassin-Naggara I, Daraï E. Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination, transvaginal sonography, rectal endoscopic sonography, and magnetic resonance imaging to diagnose deep infiltrating endometriosis. Fertility and sterility. 2009 Dec 1;92(6):1825-33.

- Chamié LP, Blasbalg R, Gonçalves MO, Carvalho FM, Abrão MS, de Oliveira IS. Accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosis and preoperative assessment of deeply infiltrating endometriosis. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2009 Sep 1;106(3):198-201.

- Vercellini P, Somigliana E, Viganò P, Abbiati A, Daguati R, Crosignani PG. Endometriosis: current and future medical therapies. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2008 Apr 1;22(2):275-306.

- Streuli I, de Ziegler D, Santulli P, Marcellin L, Borghese B, Batteux F, Chapron C. An update on the pharmacological management of endometriosis. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2013 Feb 1;14(3):291-305

- Norwitz ER, Schorge JO. Obstetrics and Gynecology at a Glance. John Wiley & Sons; 2013 Oct 14.

- Turrentine JE. Clinical protocols in obstetrics and gynecology. CRC Press; 2008 Jan 28.

- Meserve EE, Crum CP. Benign conditions of the ovary. InDiagnostic Gynecologic and Obstetric Pathology 2018 Jan 1 (pp. 761-799). Elsevier.

- Diaz JP, Sonoda Y, Leitao MM, Zivanovic O, Brown CL, Chi DS, Barakat RR, Abu-Rustum NR. Oncologic outcome of fertility-sparing radical trachelectomy versus radical hysterectomy for stage IB1 cervical carcinoma. Gynecologic oncology. 2008 Nov 1;111(2):255-60.

- Sonoda Y, Abu-Rustum NR, Gemignani ML, Chi DS, Brown CL, Poynor EA, Barakat RR. A fertility-sparing alternative to radical hysterectomy: how many patients may be eligible?. Gynecologic oncology. 2004 Dec 1;95(3):534-8.

- Das DK, Maulik N. Resveratrol in cardioprotection: a therapeutic promise of alternative medicine. Molecular interventions. 2006 Feb 1;6(1):36.

- Schmidt HH, Stocker R, Vollbracht C, Paulsen G, Riley D, Daiber A, Cuadrado A. Antioxidants in translational medicine. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2015 Nov 10;23(14):1130-43.

- Hoy S. Chasing dirt: The American pursuit of cleanliness. Oxford University Press, USA; 1995.

- Sunstein EW. Mary Shelley: romance and reality. JHU Press; 1991.

- Lin YH, Chen YH, Chang HY, Au HK, Tzeng CR, Huang YH. Chronic niche inflammation in endometriosis-associated infertility: current understanding and future therapeutic strategies. International journal of molecular sciences. 2018 Aug 13;19(8):2385.

- Cleghorn E. Unwell women: misdiagnosis and myth in a man-made world. Penguin; 2022 Jun 7.

- Bortolato B, Hyphantis TN, Valpione S, Perini G, Maes M, Morris G, Kubera M, Köhler CA, Fernandes BS, Stubbs B, Pavlidis N. Depression in cancer: the many biobehavioral pathways driving tumor progression. Cancer treatment reviews. 2017 Jan 1;52:58-70.

- Rogers PA, D’Hooghe TM, Fazleabas A, Giudice LC, Montgomery GW, Petraglia F, Taylor RN. Defining future directions for endometriosis research: workshop report from the 2011 World Congress of Endometriosis in Montpellier, France. Reproductive sciences. 2013 May;20(5):483-99.

- Sieberg CB, Lunde CE, Borsook D. Endometriosis and pain in the adolescent-striking early to limit suffering: A narrative review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2020 Jan 1;108:866-76.

- Wang Y, Nicholes K, Shih IM. The origin and pathogenesis of endometriosis. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease. 2020 Jan 24;15(1):71-95.

- Witz CA. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 1999 Sep 1;42(3):566.

- Lamceva J, Uljanovs R, Strumfa I. The main theories on the pathogenesis of endometriosis. International journal of molecular sciences. 2023 Feb 21;24(5):4254.

- Vinatier D, Orazi G, Cosson M, Dufour P. Theories of endometriosis. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2001 May 1;96(1):21-34.

- Acién P, Velasco I. Endometriosis: a disease that remains enigmatic. International Scholarly Research Notices. 2013;2013(1):242149.

- Clement PB. Endometriosis, lesions of the secondary mullerian system, and pelvic mesothelial proliferations. Blaustein's pathology of the female genital tract. 1987;3:516-9.

- Patel B, Elguero S, Thakore S, Dahoud W, Bedaiwy M, Mesiano S. Role of nuclear progesterone receptor isoforms in uterine pathophysiology. Human reproduction update. 2015 Mar 1;21(2):155-73.

- Bonavina G, Taylor HS. Endometriosis-associated infertility: From pathophysiology to tailored treatment. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2022 Oct 26;13:1020827.

- Agostinis C, Balduit A, Mangogna A, Zito G, Romano F, Ricci G, Kishore U, Bulla R. Immunological basis of the endometriosis: the complement system as a potential therapeutic target. Frontiers in immunology. 2021 Jan 11;11:599117.

- Evans J, Salamonsen LA, Winship A, Menkhorst E, Nie G, Gargett CE, Dimitriadis E. Fertile ground: human endometrial programming and lessons in health and disease. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2016 Nov;12(11):654-67.

- Zhai J, Vannuccini S, Petraglia F, Giudice LC. Adenomyosis: mechanisms and pathogenesis. InSeminars in reproductive medicine 2020 May (Vol. 38, No. 02/03, pp. 129-143). Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc..

- Smith RP, Turek P. Netter Collection of Medical Illustrations: Reproductive System: Netter Collection of Medical Illustrations: Reproductive System. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011 Feb 15.

- Aznaurova YB, Zhumataev MB, Roberts TK, Aliper AM, Zhavoronkov AA. Molecular aspects of development and regulation of endometriosis. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 2014 Dec;12:1-25.

- Malvezzi H, Marengo EB, Podgaec S, Piccinato CD. Endometriosis: current challenges in modeling a multifactorial disease of unknown etiology. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2020 Dec;18:1-21.

- Zubrzycka A, Zubrzycki M, Perdas E, Zubrzycka M. Genetic, epigenetic, and steroidogenic modulation mechanisms in endometriosis. Journal of clinical medicine. 2020 May 2;9(5):1309.

- Gordts S, Koninckx P, Brosens I. Pathogenesis of deep endometriosis. Fertility and sterility. 2017 Dec 1;108(6):872-85.

- Bulun SE, Yilmaz BD, Sison C, Miyazaki K, Bernardi L, Liu S, Kohlmeier A, Yin P, Milad M, Wei J. Endometriosis. Endocrine reviews. 2019 Aug 1;40(4):1048-79.

- International working group of AAGL, ESGE, ESHRE and WES, Tomassetti C, Johnson NP, Petrozza J, Abrao MS, Einarsson JI, Horne AW, Lee TT, Missmer S, Vermeulen N, Zondervan KT. An international terminology for endometriosis, 2021. Human Reproduction Open. 2021 Sep 1;2021(4):hoab029.

- Horne AW, Missmer SA. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of endometriosis. bmj. 2022 Nov 14;379.

- Vannuccini S, Clemenza S, Rossi M, Petraglia F. Hormonal treatments for endometriosis: The endocrine background. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. 2022 Jun;23(3):333-55.

- Impey L, Child T. Obstetrics and gynaecology. John Wiley & Sons; 2017 Jan 17.

- Laufer MR, Goldstein D. Gynecologic pain: dysmenorrhea, acute and chronic pelvic pain, endometriosis, and premenstrual syndrome. Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. Emans S, Laufer M, Goldstein D (eds). 5th edition. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia. 2005:417-76.

- Berman J, Berman L. For women only: A revolutionary guide to reclaiming your sex life. Hachette UK; 2011 Nov 10.

- Martin DC, Ling FW. Endometriosis and pain. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 1999 Sep 1;42(3):664.

- Chan PD, Johnson SM. Current clinical strategies gynecology and obstetrics. 2006.

- Tanbo T, Fedorcsak P. Endometriosis?associated infertility: aspects of pathophysiological mechanisms and treatment options. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2017 Jun;96(6):659-67.

- Abrao MS, Muzii L, Marana R. Anatomical causes of female infertility and their management. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2013 Dec 1;123:S18-24.

- Pritts EA, Taylor RN. An evidence-based evaluation of endometriosis-associated infertility. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics. 2003 Sep 1;32(3):653-67.

- Alimi Y, Iwanaga J, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. The clinical anatomy of endometriosis: a review. Cureus. 2018 Sep;10(9).

- Zwas FR, Lyon DT. Endometriosis: an important condition in clinical gastroenterology. Digestive diseases and sciences. 1991 Mar;36:353-64.

- Ek M, Roth B, Ekström P, Valentin L, Bengtsson M, Ohlsson B. Gastrointestinal symptoms among endometriosis patients—A case-cohort study. BMC women's health. 2015 Dec;15:1-0.

- Camilleri M. Management of the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2001 Feb 1;120(3):652-68.

- Chang L, Heitkemper MM. Gender differences in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002 Nov 1;123(5):1686-701.

- Rapkin AJ, Nathan L. Pelvic pain and dysmenorrhea.

- Dains JE, Baumann LC, Scheibel P. Advanced Health Assessment & Clinical Diagnosis in Primary Care-E-Book: Advanced Health Assessment & Clinical Diagnosis in Primary Care-E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015 Apr 24.

- Seller RH, Symons AB. Differential Diagnosis of Common Complaints E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011 Nov 9.

- Ferri FF. Ferri's Differential Diagnosis E-Book: A Practical Guide to the Differential Diagnosis of Symptoms, Signs, and Clinical Disorders. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2010 Aug 26.

- Woodward PJ, Sohaey R, Mezzetti Jr TP. Endometriosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2001 Jan;21(1):193-216.

- Foti PV, Farina R, Palmucci S, Vizzini IA, Libertini N, Coronella M, Spadola S, Caltabiano R, Iraci M, Basile A, Milone P. Endometriosis: clinical features, MR imaging findings and pathologic correlation. Insights into imaging. 2018 Apr;9:149-72.

- Kuligowska E, Deeds III L, Lu III K. Pelvic pain: overlooked and underdiagnosed gynecologic conditions. Radiographics. 2005 Jan;25(1):3-20.

- Jarrell JF, Vilos GA, Allaire C, Burgess S, Fortin C, Gerwin R, Lapensee L, Lea RH, Leyland NA, Martyn P, Shenassa H. No. 164-consensus guidelines for the management of chronic pelvic pain. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 2018 Nov 1;40(11):e747-87.

- Kelley AS, Moravek MB. Diagnosis and management of endometriosis. InHandbook of gynecology 2023 Dec 2 (pp. 363-372). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Moore M, Lam SJ, Kay AR. Rapid obstetrics and gynaecology. John Wiley & Sons; 2010 Sep 20.

- Rossi HR. The association of endometriosis on body size, pain perception, comorbidity and work ability in the Northern Finland Birth cohort 1966: long-term effects of endometriosis on women’s overall health.

- Layden EA, Thomson A, Owen P, Madhra M, Magowan BA, editors. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology-E-Book: Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology-E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2022 Apr 30.

- Schomacker ML, Hansen KE, Ramlau-Hansen CH, Forman A. Is endometriosis associated with irritable bowel syndrome? A cross-sectional study. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2018 Dec 1;231:65-9.

- Fritzer N, Tammaa A, Salzer H, Hudelist G. Effects of surgical excision of endometriosis regarding quality of life and psychological well-being: a review. Women’s Health. 2012 Jul;8(4):427-35.

- Chapron C, Marcellin L, Borghese B, Santulli P. Rethinking mechanisms, diagnosis and management of endometriosis. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2019 Nov;15(11):666-82.

- Falcone T, Flyckt R. Clinical management of endometriosis. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2018 Mar 1;131(3):557-71.

- Remorgida V, Ferrero S, Fulcheri E, Ragni N, Martin DC. Bowel endometriosis: presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Obstetrical & gynecological survey. 2007 Jul 1;62(7):461-70.

- Spaczynski RZ, Duleba AJ. Diagnosis of endometriosis. InSeminars in reproductive medicine 2003 (Vol. 21, No. 02, pp. 193-208). Copyright© 2003 by Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., 333 Seventh Avenue, New York, NY 10001, USA. Tel.:+ 1 (212) 584-4662.

- Veeraswamy A, Lewis M, Mann A, Kotikela S, Hajhosseini B, Nezhat C. Extragenital endometriosis. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010 Jun 1;53(2):449-66.

- Gupta S, Harlev A, Agarwal A. Endometriosis: a comprehensive update.

- Arafah M, Rashid S, Akhtar M. Endometriosis: a comprehensive review. Advances in anatomic pathology. 2021 Jan 1;28(1):30-43.

- Blamble T, Dickerson L. Recognizing and treating endometriosis. JAAPA. 2021 Jun 1;34(6):14-9.

- Vercellini P, editor. Chronic pelvic pain. John Wiley & Sons; 2011 Jan 31.

- Oyelowo T. Mosby's guide to women's health: A handbook for health professionals. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2007.

- Clark TJ. Benign conditions of the ovary and pelvis. InGynaecology by Ten Teachers 2017 May 8 (pp. 155-168). CRC Press.

- Ferrero S, Evangelisti G, Barra F. Current and emerging treatment options for endometriosis. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2018 Jul 3;19(10):1109-25.

- Ferrero S, Barra F, Leone Roberti Maggiore U. Current and emerging therapeutics for the management of endometriosis. Drugs. 2018 Jul;78(10):995-1012.

- Grandi G, Barra F, Ferrero S, Sileo FG, Bertucci E, Napolitano A, Facchinetti F. Hormonal contraception in women with endometriosis: a systematic review. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care. 2019 Jan 2;24(1):61-70.

- Barra F, Grandi G, Tantari M, Scala C, Facchinetti F, Ferrero S. A comprehensive review of hormonal and biological therapies for endometriosis: latest developments. Expert opinion on biological therapy. 2019 Apr 3;19(4):343-60.

- Sabry M, Al-Hendy A. Medical treatment of uterine leiomyoma. Reproductive sciences. 2012 Apr;19(4):339-53.

- Singh SS, Belland L. Contemporary management of uterine fibroids: focus on emerging medical treatments. Current medical research and opinion. 2015 Jan 2;31(1):1-2.

- Barra F, Scala C, Ferrero S. Current understanding on pharmacokinetics, clinical efficacy and safety of progestins for treating pain associated to endometriosis. Expert opinion on drug metabolism & toxicology. 2018 Apr 3;14(4):399-415.

- Ferrero S, Venturini PL, Ragni N, Camerini G, Remorgida V. Pharmacological treatment of endometriosis: experience with aromatase inhibitors. Drugs. 2009 May;69:943-52.

- Vercellini P, Viganò P, Somigliana E, Fedele L. Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2014 May;10(5):261-75.

- Maggiore UL, Ferrero S, Candiani M, Somigliana E, Vigano P, Vercellini P. Bladder endometriosis: a systematic review of pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, impact on fertility, and risk of malignant transformation. European urology. 2017 May 1;71(5):790-807

- Adamson GD, Nelson HP. Surgical treatment of endometriosis. Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America. 1997 Jun 1;24(2):375-409.

- Adamson D. Surgical management of endometriosis. InSeminars in reproductive Medicine 2003 (Vol. 21, No. 02, pp. 223-234). Copyright© 2003 by Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., 333 Seventh Avenue, New York, NY 10001, USA. Tel.:+ 1 (212) 584-4662.

- Null G, Seaman B. For women only!: your guide to health empowerment. Seven Stories Press; 2001.

- Tollefson M, Eriksen N, Pathak N, editors. Improving women’s health across the lifespan. CRC Press; 2021 Oct 24.

- Earle L. The Good Menopause Guide. Orion Spring; 2018 Mar 8.

- Harper J. Your fertile years: What you need to know to make informed choices. Hachette UK; 2021 Apr 29.

- Warshowsky A, Oumano E. Healing fibroids: A doctor's guide to a natural cure. Simon and Schuster; 2010 May 11.

- Viganò P, Parazzini F, Somigliana E, Vercellini P. Endometriosis: epidemiology and aetiological factors. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2004 Apr 1;18(2):177-200.

- Mehedintu C, Plotogea MN, Ionescu S, Antonovici M. Endometriosis still a challenge. Journal of medicine and life. 2014 Sep 9;7(3):349.

- Monnin N, Fattet AJ, Koscinski I. Endometriosis: update of pathophysiology,(epi) genetic and environmental involvement. Biomedicines. 2023 Mar 22;11(3):978.

- Dörk T, Hillemanns P, Tempfer C, Breu J, Fleisch MC. Genetic susceptibility to endometrial cancer: Risk factors and clinical management. Cancers. 2020 Aug 25;12(9):2407.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Malspeis S, Willett WC, Hunter DJ. Reproductive history and endometriosis among premenopausal women. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2004 Nov 1;104(5 Part 1):965-74.

- Kampert JB, Whittemore AS, Paffenbarger Jr RS. Combined effect of childbearing, menstrual events, and body size on age-specific breast cancer risk. American journal of epidemiology. 1988 Nov 1;128(5):962-79.

- Jones RE, Lopez KH. Human reproductive biology. Academic Press; 2013 Sep 28.

- Kim SI, Swanson TA, Chen RC. Obstetrics and gynecology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

- Chard T, Lilford R. Basic sciences for obstetrics and gynaecology. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013 Dec 1.

- O'Reilly B, Bottomley C, Rymer J. Essentials of Obstetrics and Gynaecology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012 Apr 25.

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon JP, Giudice LC, Hauser R, Prins GS, Soto AM, Zoeller RT, Gore AC. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocrine reviews. 2009 Jun 1;30(4):293-342.

- Giulivo M, de Alda ML, Capri E, Barceló D. Human exposure to endocrine disrupting compounds: Their role in reproductive systems, metabolic syndrome and breast cancer. A review. Environmental research. 2016 Nov 1;151:251-64.

- Crain DA, Janssen SJ, Edwards TM, Heindel J, Ho SM, Hunt P, Iguchi T, Juul A, McLachlan JA, Schwartz J, Skakkebaek N. Female reproductive disorders: the roles of endocrine-disrupting compounds and developmental timing. Fertility and sterility. 2008 Oct 1;90(4):911-40.

- Yang M, Park MS, Lee HS. Endocrine disrupting chemicals: human exposure and health risks. Journal of Environmental Science and Health Part C. 2006 Dec 1;24(2):183-224.

- Papanicolaou DA, Wilder RL, Manolagas SC, Chrousos GP. The pathophysiologic roles of interleukin-6 in human disease. Annals of internal medicine. 1998 Jan 15;128(2):127-37.

- Kalagiri RR, Carder T, Choudhury S, Vora N, Ballard AR, Govande V, Drever N, Beeram MR, Uddin MN. Inflammation in complicated pregnancy and its outcome. American journal of perinatology. 2016 Dec;33(14):1337-56.

- Reis FM, Coutinho LM, Vannuccini S, Luisi S, Petraglia F. Is stress a cause or a consequence of endometriosis?. Reproductive Sciences. 2020 Jan;27:39-45.

- Hart RJ. Physiological aspects of female fertility: role of the environment, modern lifestyle, and genetics. Physiological reviews. 2016 Jul;96(3):873-909.

- Bieber EJ, Sanfilippo JS, Horowitz IR, Shafi MI, editors. Clinical gynecology. Cambridge University Press; 2015 Apr 23.

- Arafah M, Rashid S, Akhtar M. Endometriosis: a comprehensive review. Advances in anatomic pathology. 2021 Jan 1;28(1):30-43.

- Wójcik M, Szczepaniak R, Placek K. Physiotherapy management in endometriosis. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2022 Dec 2;19(23):16148

- Saunders PT, Horne AW. Endometriosis: Etiology, pathobiology, and therapeutic prospects. Cell. 2021 May 27;184(11):2807-24.

- Laganà AS, Garzon S, Götte M, Viganò P, Franchi M, Ghezzi F, Martin DC. The pathogenesis of endometriosis: molecular and cell biology insights. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019 Nov 10;20(22):5615.

- Aznaurova YB, Zhumataev MB, Roberts TK, Aliper AM, Zhavoronkov AA. Molecular aspects of development and regulation of endometriosis. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 2014 Dec;12:1-25.

- Zhang T, De Carolis C, Man GC, Wang CC. The link between immunity, autoimmunity and endometriosis: a literature update. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2018 Oct 1;17(10):945-55.

- Bulun SE, Yilmaz BD, Sison C, Miyazaki K, Bernardi L, Liu S, Kohlmeier A, Yin P, Milad M, Wei J. Endometriosis. Endocrine reviews. 2019 Aug 1;40(4):1048-79.

- Perera F, Herbstman J. Prenatal environmental exposures, epigenetics, and disease. Reproductive toxicology. 2011 Apr 1;31(3):363-73.

- Mallozzi M, Leone C, Manurita F, Bellati F, Caserta D. Endocrine disrupting chemicals and endometrial cancer: an overview of recent laboratory evidence and epidemiological studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017 Mar;14(3):334.

- Bruner-Tran KL, Gnecco J, Ding T, Glore DR, Pensabene V, Osteen KG. Exposure to the environmental endocrine disruptor TCDD and human reproductive dysfunction: translating lessons from murine models. Reproductive Toxicology. 2017 Mar 1;68:59-71.

- Sofo V, Götte M, Laganà AS, Salmeri FM, Triolo O, Sturlese E, Retto G, Alfa M, Granese R, Abrão MS. Correlation between dioxin and endometriosis: an epigenetic route to unravel the pathogenesis of the disease. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics. 2015 Nov;292:973-86.

- Coutinho LM, Ferreira MC, Rocha AL, Carneiro MM, Reis FM. New biomarkers in endometriosis. Advances in clinical chemistry. 2019 Jan 1;89:59-77.

- Suvitie P. Modern methods of Evaluating endometriosis. Publications of the University of Turku-Annales Universitatis Turkuensis. https://www. utu. fi/en/units/library/requestbuypublish/publi sh/publishing-doctoral-dissertation/annalesserial/Pages/home. aspx. 2018.

- Carbone MG, Campo G, Papaleo E, Marazziti D, Maremmani I. The importance of a multi-disciplinary approach to the endometriotic patients: the relationship between endometriosis and psychic vulnerability. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021 Apr 10;10(8):1616.

- Giudice LC. Advances in approaches to diagnose endometriosis. Global Reproductive Health. 2024 Apr 1;9(1):e0074.

- Vickramarajah S, Stewart V, van Ree K, Hemingway AP, Crofton ME, Bharwani N. Subfertility: what the radiologist needs to know. RadioGraphics. 2017 Sep;37(5):1587-602.

- Dabi Y, Suisse S, Puchar A, Delbos L, Poilblanc M, Descamps P, Haury J, Golfier F, Jornea L, Bouteiller D, Touboul C. Endometriosis-associated infertility diagnosis based on saliva microRNA signatures. Reproductive BioMedicine Online. 2023 Jan 1;46(1):138-49.

- Simopoulou M, Sfakianoudis K, Tsioulou P, Rapani A, Pantos K, Koutsilieris M. Dilemmas regarding the management of endometriosis-related infertility. Annals of Research Hospitals. 2019 Feb 11;3.

- Istrate-Ofi?eru AM, Mogoant? CA, Zoril? GL, Ro?u GC, Dr?gu?in RC, Berbecaru EI, Zoril? MV, Com?nescu CM, Mogoant? S?, Vaduva CC, Br?til? E. Clinical Characteristics and Local Histopathological Modulators of Endometriosis and Its Progression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024 Feb 1;25(3):1789.

- Donnez J, Dolmans MM. Fertility preservation in women. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2013 Dec;9(12):735-49.

- Bedoschi G, Oktay K. Current approach to fertility preservation by embryo cryopreservation. Fertility and sterility. 2013 May 1;99(6):1496-502.

- Rodriguez-Wallberg KA, Oktay K. Options on fertility preservation in female cancer patients. Cancer treatment reviews. 2012 Aug 1;38(5):354-61.

- Maddern J, Grundy L, Castro J, Brierley SM. Pain in endometriosis. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience. 2020 Oct 6;14:590823.

- Machairiotis N, Vasilakaki S, Thomakos N. Inflammatory mediators and pain in endometriosis: a systematic review. Biomedicines. 2021 Jan 8;9(1):54.

- Horne AW, Missmer SA. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of endometriosis. bmj. 2022 Nov 14;379.

- Kim IS. Current perspectives on the beneficial effects of soybean isoflavones and their metabolites for humans. Antioxidants. 2021 Jun 30;10(7):1064.

- Clower L, Fleshman T, Geldenhuys WJ, Santanam N. Targeting oxidative stress involved in endometriosis and its pain. Biomolecules. 2022 Jul 29;12(8):1055.

- Maeng LY, Beumer A. Never fear, the gut bacteria are here: Estrogen and gut microbiome-brain axis interactions in fear extinction. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2023 Jul 1;189:66-75.

- Bortolato B, Hyphantis TN, Valpione S, Perini G, Maes M, Morris G, Kubera M, Köhler CA, Fernandes BS, Stubbs B, Pavlidis N. Depression in cancer: the many biobehavioral pathways driving tumor progression. Cancer treatment reviews. 2017 Jan 1;52:58-70.

- Houghton LA, Heitkemper M, Crowell MD, Emmanuel A, Halpert A, McRoberts JA, Toner B. Age, gender, and women’s health and the patient. Gastroenterology. 2016 May 1;150(6):1332-43.

- Cuevas M, Flores I, Thompson KJ, Ramos-Ortolaza DL, Torres-Reveron A, Appleyard CB. Stress exacerbates endometriosis manifestations and inflammatory parameters in an animal model. Reproductive Sciences. 2012 Aug;19(8):851-62.

- Rowe HJ, Hammarberg K, Dwyer S, Camilleri R, Fisher JR. Improving clinical care for women with endometriosis: qualitative analysis of women’s and health professionals’ views. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2021 Jul 3;42(3):174-80.

- Leonardi M, Horne AW, Vincent K, Sinclair J, Sherman KA, Ciccia D, Condous G, Johnson NP, Armour M. Self-management strategies to consider to combat endometriosis symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Human Reproduction Open. 2020;2020(2):hoaa028.

- Carey ET, Till SR, As-Sanie S. Pharmacological management of chronic pelvic pain in women. Drugs. 2017 Mar;77:285-301.

- Gao C, Outley JK, Botteman M, Spalding J, Simon JA, Pashos CL. The economic burden of endometriosis. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006 Apr 1;107(4):22S.

- Rogers PA, Adamson GD, Al-Jefout M, Becker CM, D’Hooghe TM, Dunselman GA, Fazleabas A, Giudice LC, Horne AW, Hull ML, Hummelshoj L. Research priorities for endometriosis: recommendations from a global consortium of investigators in endometriosis. Reproductive sciences. 2017 Feb;24(2):202-26.

- Staal AH, Van Der Zanden M, Nap AW. Diagnostic delay of endometriosis in the Netherlands. Gynecologic and obstetric investigation. 2016 Jul 6;81(4):321-4.

Sakshi Kumari *

Sakshi Kumari *

Sonu Sharma

Sonu Sharma

10.5281/zenodo.14223692

10.5281/zenodo.14223692