Abstract

Drug delivery still faces difficulties in overcoming biological barriers. The purpose of biological barriers is to provide defense against harmful substances and diseases, which are situated appropriately. There are two types of drugs: hydrophilic and hydrophobic. Drugs that are hydrophilic are lipid insoluble, whereas those that are hydrophobic are either water insoluble or only marginally soluble. Drug nature plays a significant role in determining the mode of administration, pharmacokinetics (i.e., ADME), and the type of organ impacted, namely lead. Furthermore, the mode of delivery is also determined by the type of sickness. Currently, dendrimers, nanogels, chitosan-based nanoparticles, liposomes, nanogels, micelles, nanoemulsion, and metallic nanoparticles are used to improve the uptake of hydrophobic medications across biological barriers, whereas dendrimers, nanogels, and liposomes are used for hydrophilic pharmaceuticals. The use of nanotechnology to deliver drugs across various biological barriers—whether hydrophilic or hydrophobic—is one of the most recent developments in medication research. All of the methods discussed play specific roles, such as improving stability, efficacy, deformability, or penetration through cell injections and plasma membranes. By using these strategies, researchers are attempting to address microbial resistance and cancer. However, a great deal of study is still needed to create medicines that work without these obstacles. An overview of multiple biological barriers and different approaches to solving the drug transport issue and guaranteeing effective delivery of medicinal chemicals to their targets are given in this paper.

Keywords

Anti-bacterial, Halitosis, Herbal mouthwash, swished, Oral pathogens.

Introduction

Preface The word" hedge" frequently refers to a natural or man- made structure that restricts movement or access. It comes from the Old French word “barrier", which meant a precipice or fort guarding an entry. thus, the Oxford English Dictionary defines" hedge" as" a natural conformation or structure that prevents or hinders movement or action." Merriam- Webster defines" a hedge as a natural conformation or structure that prevents or hinders movement or action. "Samuel Johnson Dictionary defines" hedge,"" entrenchment," and" boundary." The final statement, which makes reference to the idea of inhibition, seems to allow for some choice of movement, whereas the utmost of the descriptions over are basically confined to a double understanding of a hedge as either being complete or broken. Interestingly, the authors who first created the term “hemato- encephalic hedge” (restated from French) importantly believed it “to play the part of a picky hedge” (1). The blood- brain hedge( BBB), air- blood hedge, Mucosal hedge, skin hedge, placental hedge, and intestinal hedge are just a many exemplifications of the natural walls set up in the body. These walls are structures that divide the surroundings on either side of them and control the exchange of accoutrements and signals between them. [2-5]. these walls are essential for conserving the body's health because they keep pathogens and dangerous substances out of the body, where they can beget infection or injury. On the other hand, by keeping specifics from getting to the intended apkins, these walls may potentially reduce their effectiveness. [3- 5] Experimenters are probing the use of nanoparticles as a medicine delivery system (DDS) because of the difficulty in prostrating these obstacles. Certain nanoparticles, like gold nanoparticles, have size-dependent capability to pass through the natural hedge.[6] nonetheless, this strategy is active, subject to strict limitations on nanoparticle size, and prone to adding up nanoparticles in areas that are n't intended.( 6,7)

Targeting targeted and effective tumor delivery can enhance the immune response inside tumors while preventing or minimizing inflammatory and other harmful autoimmune processes in adjacent organs, which would be beneficial for the newest immunotherapies such immune checkpoint inhibitors [8]. Biological barriers (BBs) provide defense against disease-causing organisms and invaders, but they also make it more difficult to transport medications to their intended locations. The blood-brain barrier (BBB), blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCSFB), blood-lymph barrier (BlyB), blood-air barrier (BAB), stromal barrier (SB), blood-labyrinth barrier (BLaB), blood-retinal barrier (BRB), and placental barrier (PB) are just a few of the many BBs that surround particular tissue regions and organs in the human body (as illustrated in Figure 1) [9].The immune-suppressive milieu and the stromal barrier may hinder the ability of cytotoxic T lymphocytes to eradicate cancer cells. Restricting the penetration of nanoparticles. The ability of nanotherapeutic drugs to enter tumors can be restricted by the stromal barrier. This is brought about by the stromal cells high density, which has the ability to compress the matrix and produce an unstructured network, encouraging the growth of tumors. The blood-brain barrier (BBB) and the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCSFB) have shielded certain tissues from pharmacological access. As promising prospects, dendrimers, nanoparticles, liposomes, hydrogels, and cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) have all risen and gone [10].Efflux pumps, tight junctions, molecule size for passive transport, receptor-mediated transport, and enzyme saturation are important elements in the BB microenvironment that allow for efficient drug uptake and bioavailability, which is necessary for creating safe and efficient delivery methods [11].

BBB: blood brain barrier: One of the bodily barriers that have been investigated the most is the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which is also one of the hardest to cross. This is caused by a variety of issues pertaining to the various elements required to preserve the integrity and functionality of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), such as controlling cerebral blood flow, permeability, and preservation of elements such the highly specialized endothelial cells found in tight junctions [12]. Additionally, the brain's parenchyma and other cells have the ability to absorb them [13]. Exosomal miRNAs and lncRNAs have been demonstrated to mediate microglial cell polarization [14], inhibiting the uptake of glucose in brain astrocytes [15].

Blb: blood lymph barrier: Currently being investigated and uncovered is the functional connection between the blood–lymph barrier (BLyB) and the blood–brain barrier (BBB) [16] Recent research has shown that the brain circulates CNS-derived chemicals and lymphocytes, and that the glymphatic system drains CSF into cervical lymph nodes [17]. These results raise the intriguing prospect of overcoming the BLyB to reach the brain parenchyma and possibly get beyond other biological barriers found throughout the body [18]. The lymphatic system interacts with the brain and CSF through the glymphatic system, as evidenced by the rapidly expanding body of research over the past 20 years [19]. This may be important for treating disease invasions and preserving normal function. Research on engineered DC exosomes, including surface receptor engineering [20] and cargo loading [21], has increased in order to provide more potent and targeted delivery in the development of cancer immunotherapy [22-23] and other disease treatments [24]. More knowledge of recipient cells, transit, surface ligands, and cargo of exosomes, along with their access to the lymphatic system and movement across and within the BLyB, is needed for the development of a feasible therapeutic pathway.

Bab: blood air barrier: Although the BAB is essential for successfully limiting the migration of infections, this defensive mechanism also prevents the effects of therapeutic therapies [25]. The three primary barriers of mechanical, chemical, and immunological barriers enable the obstruction and clearance of infections and therapeutic medications [26]. Defensins, neutrophils, macrophages, T and B lymphocytes, chemokines, and cytokines are just a few of the immunological cells that may be found in the mucosa, which is made up of the epithelium, lamina propria, and smooth muscle [27]. The pulmonary air space's epithelium layer is shielded by the intricate network of the "bronchial tree" in the alveolated area [28]. Surfactant secretion and gas exchange take place in the alveolar epithelium [29].

Sb: stromal barrier: The sole pathological barriers discussed in this review are stromal barriers (SBs), which provide significant challenges to cancer treatment. One of the primary causes of death in the world is still cancer. Solid tumors continue to resist promising treatments such as antibodies, small molecules, nanodrugs, and antibody drug conjugates, despite increased efforts and innovative medications [30]. Moreover, poor results are caused by intrinsic and acquired drug resistance [31], inadequate selective penetration, and restricted identification of therapeutic targets [32]. Targeted administration becomes more difficult when access to malignant tissue is gained, as seen, for instance, in epithelial-derived malignancies, due to the variability of the SBs in the same and different anatomic regions [33].

Blab: Blood Labyrinth Barrier: Given how similar the BlAB and BRB are to one another, these two barriers are covered in one part to provide light on the state of the research and the development of exosome therapy. The spiral ligament and stria vascularis were described as

Hawkins identified the integral structures for the BLaB barrier [34] in 1960. More specialized stria vascularis structures were identified, including basal and marginal cell tight connections within the perilymph and endolymph barriers, respectively [35]. The blood–endolymph barrier, blood perilymph barrier, cerebrospinal fluid–perilymph barrier, middle ear–labyrinth barrier, and Endolymph– perilymph barrier are the five interrelated but independent membranous labyrinth barriers that have recently been proposed as a subset of the BLaB [36].

Pb: placental barrier: Similarities across barrier systems include the endothelium's role as the inner BRB and BB's anatomic substrate [37]. Similarities exist between the placental barrier (BPB) and the blood–thymus barrier as well as between the outer BRB and the barrier formed of

Comprising epithelial cells with a high expression of transporters, few pinocytotic vesicles, dense intercellular connections, and enhanced molecular exchange selectivity. It serves as the primary maternofetal contact in addition to shielding the growing fetus from harmful substances [38]. Moreover, the PB performs endocrine organ tasks [39]. Furthermore, the placenta's fetal endocrine signals activate immune cells [40,41], block progesterone [42,43], and disrupt homeostasis in an inflammatory process that prepares the uterus for parturition [44,45]. The STB layer also acts as an endocrine organ, synthesizing progesterone, estrogen, and growth hormones [46].

DISCUSSION: The intricacy and diversity of several distinct BBs have hindered and complicated efforts to better understand and cure illness. Although the history and recent developments are included here, this is not a comprehensive analysis because there are several defenses against each barrier, some of which are still undiscovered. Drug distribution at local locales, for instance, frequently requires crossing BBs with mucosal surfaces, including those seen in the BAB and BRB. On the other hand, human mucus is typically 10–100 micrometers thick and is entangled with mucin and biomacromolecules in crosslinked strands strengthened by disulfide connections [47]. Exosome subtypes and sources, which are currently poorly known, may cause exosomes to cross BBs through a variety of receptors [48].

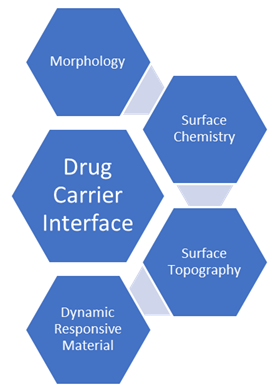

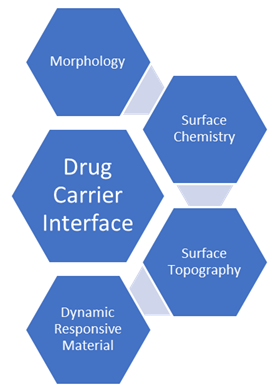

Drug carrier interface:

Numerous fabrication techniques have been used to create drug carriers from a wide range of material components. Through material physicochemical engineering, the biointerface with the biological barrier of interest can be altered for each of these carrier groups. Surface chemistry, surface topography, and drug carrier morphology are the three most crucial engineering factors to take into account [49].

Morphology: The size, shape, and stiffness of the material make up the morphology of drug carriers. These factors are crucial for particle-based drug delivery methods, but they are also crucial for the creation of micro or nanostructured components for use in macroscale drug reservoirs or delivery systems. The shape of the drug carrier particle affects all aspects of its biointerface, independent of the material—including inorganic particles—that it is made of [50].

Surface chemistry: Since the material surface of drug carriers comes into direct contact with biological systems, the chemistry on the surface is arguably the most crucial element to engineer in order to manage the material biointerface. It is crucial to take into account both the drug carrier's and the biological barrier's surface chemistry in order to regulate interactions between the two. Positively charged chitosan-coated drug carriers made to stick to negatively charged mucosal surfaces are an example of how complimentary electrostatic interactions can be applied to a material surface if adhesive forces are required [51].

Surface Topography: Surface topography can also be crucial in the interactions between material surfaces and biological barriers to drug delivery, such as immune system interactions, cellular membrane penetration, and epithelial tight junction permeabilization, even though micro and nanotopography have been thoroughly studied in the domains of biofouling and tissue engineering [52].

Dynamic responsive materials: These responsive materials were mainly created to enhance drug localization to the target site in the context of drug delivery. Although the field of drug delivery benefits from this strategy, in this review we concentrate on materials that overcome biological barriers to drug administration by changing their physicochemical characteristics, such as surface charge or shape, in response to a stimulus of interest. Additionally, we emphasize stimulus-responsive nano and micromotors, which can change the dynamics of particle movement in response to chemical or biological inputs [53].

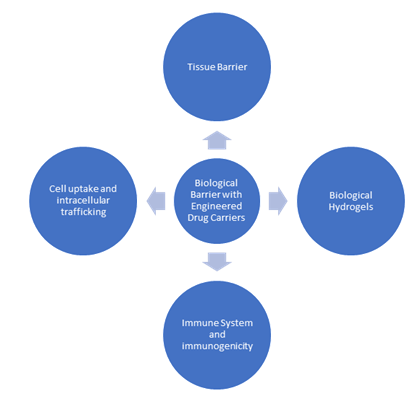

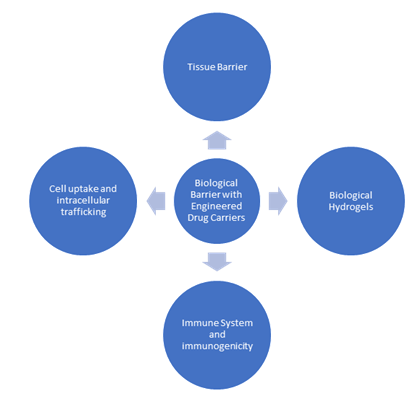

Biological barrier with Engineered Drug carriers:

These biological barriers present particular difficulties for drug carriers entering the body and navigating to their tissue target, but they are also essential physiological elements that shield the body from invasive pathogens and preserve homeostasis. In order to enhance drug delivery results, we will present examples of novel material designs that enable dynamic biointerfacing between drug carriers and biological barriers in this section [54]. Mucus serves as a protective barrier lining respiratory systems and mucosal surfaces, including those in the GI. For efficient mucosal medication delivery, certain formulations are needed since mucus can trap and impede drug absorption.

Tissue barrier: The most common biological barrier for medication administration is tissue. Comprising densely packed cells, these barriers can restrict medication entry into the bloodstream by preventing paracellular transport between cells as well as transcytosis through and across the cell [55]. Many drug delivery targets and administration routes, such as ocular, transdermal, oral, and lung distribution, are complicated by epithelial barriers and TJs [70]. Endothelial barriers, like the blood-barrier (BBB), which restricts the amount of medication that may reach the brain after intravenous injection, can also prevent drug transport in addition to epithelial barriers [56].

Biological hydrogels: Since medications and drug carriers must pass through biological hydrogels before they can reach their disease target, biological hydrogels, which are found throughout the body, provide serious obstacles to efficient drug delivery. The intrinsic porosities and material characteristics of biological hydrogels, like those of other hydrogel systems, restrict particle penetration through steric filtering and chemical interactions like electrostatics [57].

Biological hydrogels, as opposed to synthetic hydrogel systems, are dynamic biomaterials that experience changes and perturbations to their mechanical and chemical characteristics to preserve homeostasis or in reaction to illness or stress [58].

Immune System and Immunogenicity: First, a particle protein corona made of plasma proteins is formed. Next, drug carriers may be quickly absorbed by innate immune system phagocytes, demonstrating a robust immune system that could result in particle clearance [59].

Particle opsonization is caused by the mononuclear phagocytic system (MPS), which results in high particle clearance rates and ineffective treatment responses [60].

Cell uptake and intracellular trafficking: The intracellular barrier is the final biological barrier through which therapeutic medicines can be delivered. Cellular uptake and intracellular routing are essential for effective medication delivery since the target site of many therapeutic medicines is located inside the cell. The most difficult therapeutic agents to administer intracellularly include large macromolecules, tiny hydrophilic medications, and nucleic acids because of the low pH in endosomes and lysosomes, the lysosomal enzymes, and the cytosolic redox environment.

CONCLUSION: In the field of pharmaceutical science, the intricacy of biological barriers in medication distribution presents both opportunities and challenges. These barriers—which include the immune system, the GI barrier, the placenta barrier, and the blood-brain barrier—are essential for preserving the body's health and shielding it from damage. Nevertheless, there are limitations on the effective and focused distribution of medications. The goal of ongoing medication delivery technology research and development is to get past these biological obstacles.As we learn more about these biological obstacles, the possibility of safer and more efficient medication therapy increases. The quality of life for people in need of medical intervention can be improved by taking advantage of our understanding of these challenges and the most recent developments in drug delivery science to create treatments that are not only more effective but also more individualized and targeted. The continuous endeavor to surmount these problems holds the potential to transform healthcare and offer people dealing with a variety of health issues fresh hope.

REFERENCES

- Stern L, Gautier R. Recherches sur le liquide céphalo rachidien: I. Les rapports entre le liquide céphalorachidien ET la circulation sanguine. Archiv Int Physiol. 1921; 17(2):138–92{https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:84432005}

- Nanoparticles: a review of in vitro and in vivo studies. Chem Soc Rev Harris-Tryon TA, Grice EA. Microbiota and maintenance of skin barrifunction. Science. 2022; 376: 940-945.

- Arumugasaamy N, Rock KD, Kuo CY, Bale TL, Fisher JP. Microphysiological systems of the placental barrier. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2020; 161-162:161-175. Doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.08.010. Pub 2020 Aug 26. PMID: 32858104; PMCID: PMC10288517.

- Camilleri M. Leaky gut: mechanisms, measurement and clinical implications in humans. Gut. 2019 Aug; 68 (8):1516-1526. Doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318427. Epub 2019 May 10. PMID: 31076401; PMCID: PMC6790068.

- Kreyling WG, Hirn S, Möller W, Schleh C, Wenk A, Celik G, Lipka J, Schäffler M, Haberl N, Johnston BD, Sperling R, Schmid G, Simon U, Parak WJ, Semmler-Behnke M. Air-blood barrier translocation of tracheally instilled gold nanoparticles inversely depends on particle size. ACS Nano. 2014 Jan 28;8 (1):222-33. Doi: 10.1021/nn403256v. Epub 2013 Dec 30. PMID: 24364563; PMCID: PMC3960853.

- Khlebtsov N, Dykman L. Biodistribution and toxicity of engineered gold nanoparticles: a review of in vitro and in vivo studies. Chem Soc Rev. 2011 Mar;40(3):1647-71. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00018c. Epub 2010 Nov 16. PMID: 21082078.

- Postow MA, Callahan MK, Wolchok JD. Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Cancer Therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Jun 10;33 (17):1974-82. Doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.4358. Epub 2015 Jan 20. PMID: 25605845; PMCID: PMC4980573.

- Beal J. Bridging the gap: a roadmap to breaking the biological design barrier. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2015 Jan 20; 2:87. Doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2014.00087. PMID: 25654077; PMCID: PMC4299508.

- Ferraris C, Cavalli R, Panciani PP, Battaglia L. Overcoming the Blood-Brain Barrier: Successes and Challenges in Developing Nanoparticle-Mediated Drug Delivery Systems for the Treatment of Brain Tumours. Int J Nanomedicine. 2020 Apr 30; 15:2999-3022. Doi: 10.2147/IJN.S231479. PMID: 32431498; PMCID: PMC7201023.

- Serlin Y, Shelef I, Knyazer B, Friedman A. Anatomy and physiology of the blood-brain barrier. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015 Feb; 38:2-6. Doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.01.002. Epub 2015 Feb 11. PMID: 25681530; PMCID: PMC4397166.

- Abbott NJ, Rönnbäck L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006 Jan;7 (1):41-53. Doi: 10.1038/nrn1824. PMID: 16371949.

- Morad G, Carman CV, Hagedorn EJ, Perlin JR, Zon LI, Mustafaoglu N, Park TE, Ingber DE, Daisy CC, Moses MA. Tumor-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Breach the Intact Blood-Brain Barrier via Transcytosis. ACS Nano. 2019 Dec 24; 13(12):13853-13865. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b04397. Epub 2019 Sep 10. PMID: 31479239; PMCID: PMC7169949.

- Fong, M.Y.; Zhou, W.; Liu, L.; Alontaga, A.Y.; Chandra, M.; Ashby, J.; Chow,

- A.; O’Connor, S.T.; Li, S.; Chin, A.R.; et al. Breast cancer-secreted mir-122 reprograms glucose metabolism in premetastatic niche to promote metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 183–194. [crossref]

- Xing F, Liu Y, Wu SY, Wu K, Sharma S, Mo YY, Feng J, Sanders S, Jin G, Singh R, Vidi PA, Tyagi A, Chan MD, Ruiz J, Debinski W, Pasche BC, Lo HW, Metheny-Barlow LJ, D'Agostino RB Jr, Watabe K. Loss of XIST in Breast Cancer Activates MSN-c-Met and Reprograms Microglia via Exosomal mirna to Promote Brain Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2018 Aug 1; 78(15):4316-4330. Doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-1102. Epub 2018 Jul 19. Erratum in: Cancer Res. 2021 Nov 1; 81(21):5582. Doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-3056. PMID: 30026327; PMCID: PMC6072593.

- Engelhardt B, Vajkoczy P, Weller RO. The movers and shakers in immune privilege of the CNS. Nat Immunol. 2017 Feb; 18(2):123-131. Doi: 10.1038/ni.3666. Epub 2017 Jan 16. PMID: 28092374.

- MEDAWAR PB. Immunity to homologous grafted skin; the fate of skin homografts transplanted to the brain, to subcutaneous tissue, and to the anterior chamber of the eye. Br J Exp Pathol. 1948 Feb; 29(1):58-69. PMID: 18865105; PMCID: PMC2073079.

- Aspelund A, Antila S, Proulx ST, Karlsen TV, Karaman S, Detmar M, Wiig H, Alitalo K. A dural lymphatic vascular system that drains brain interstitial fluid and macromolecules. J Exp Med. 2015 Jun 29; 212(7):991-9. Doi: 10.1084/jem.20142290. Epub 2015 Jun 15. PMID: 26077718; PMCID: PMC4493418.

- Louveau A, Smirnov I, Keyes TJ, Eccles JD, Rouhani SJ, Peske JD, Derecki NC, Castle D, Mandell JW, Lee KS, Harris TH, Kipnis J. Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature. 2015 Jul 16; 523(7560):337-41. Doi: 10.1038/nature14432. Epub 2015 Jun 1. Erratum in: Nature. 2016 Feb 24; 533(7602):278. Doi: 10.1038/nature16999. PMID: 26030524; PMCID: PMC4506234.

- Jessen NA, Munk AS, Lundgaard I, Nedergaard M. The Glymphatic System: A Beginner's Guide. Neurochem Res. 2015 Dec; 40(12):2583-99. Doi: 10.1007/s11064-015-1581-6. Epub 2015 May 7. PMID: 25947369; PMCID: PMC4636982.

- Louveau A, Harris TH, Kipnis J. Revisiting the Mechanisms of CNS Immune Privilege. Trends Immunol. 2015 Oct; 36(10):569-577.Doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.08.006. PMID: 26431936; PMCID: PMC4593064

- Zhao Z, McGill J, Gamero-Kubota P, He M. Microfluidic on-demand engineering of exosomes towards cancer immunotherapy. Lab Chip. 2019 May 14; 19(10):1877-1886. Doi: 10.1039/c8lc01279b. PMID: 31044204; PMCID: PMC6520140.

- Zhu Q, Heon M, Zhao Z, He M. Microfluidic engineering of exosomes: editing cellular messages for precision therapeutics. Lab Chip. 2018 Jun 12;18(12):1690-1703. doi: 10.1039/c8lc00246k. PMID: 29780982; PMCID: PMC5997967.

- Zhang P, Liu RT, Du T, Yang CL, Liu YD, Ge MR, Zhang M, Li XL, Li H, Dou YC, Duan RS. Exosomes derived from statin-modified bone marrow dendritic cells increase thymus-derived natural regulatory T cells in experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis. J Neuroinflammation. 2019 Nov 3; 16(1):202. Doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1587-0. PMID: 31679515; PMCID: PMC6825716.

- Shi S, Rao Q, Zhang C, Zhang X, Qin Y, Niu Z. Dendritic Cells Pulsed with Exosomes in Combination with PD-1 Antibody Increase the Efficacy of Sorafenib in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Model. Transl Oncol. 2018 Apr;11(2):250-258. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2018.01.001. Epub 2018 Jan 28. PMID: 29413757; PMCID: PMC5789129.

- Leone DA, Rees AJ, Kain R. Dendritic cells and routing cargo into exosomes. Immunol Cell Biol. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1111/imcb.12170. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 29797348.

- Tian H, Li W. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes for cancer immunotherapy: hope and challenges. Ann Transl Med. 2017 May;5(10):221. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.02.23. PMID: 28603736; PMCID: PMC5451628.

- Elashiry M, Elashiry MM, Elsayed R, Rajendran M, Auersvald C, Zeitoun R, Rashid MH, Ara R, Meghil MM, Liu Y, Arbab AS, Arce RM, Hamrick M, Elsalanty M, Brendan M, Pacholczyk R, Cutler CW. Dendritic cell derived exosomes loaded with immunoregulatory cargo reprogram local immune responses and inhibit degenerative bone disease in vivo. J Extracell Vesicles. 2020 Aug 7;9(1):1795362. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2020.1795362. Erratum in: J Extracell Vesicles. 2021 Jul;10(9):e12115. doi: 10.1002/jev2.12115. PMID: 32944183; PMCID: PMC7480413.

- Labiris NR, Dolovich MB. Pulmonary drug delivery. Part I: physiological factors affecting therapeutic effectiveness of aerosolized medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003 Dec;56(6):588-99. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01892.x. PMID: 14616418; PMCID: PMC1884307.

- Sudduth ER, Trautmann-Rodriguez M, Gill N, Bomb K, Fromen CA. Aerosol pulmonary immune engineering. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2023 Aug;199:114831. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2023.114831. Epub 2023 Apr 24. PMID: 37100206; PMCID: PMC10527166.

- Anderson MJ, Parks PJ, Peterson ML. A mucosal model to study microbial biofilm development and anti-biofilm therapeutics. J Microbiol Methods. 2013 Feb 15;92(2):201-8. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.12.003. Epub 2012 Dec 14. PMID: 23246911; PMCID: PMC3570591.

- Newman SP. Drug delivery to the lungs: challenges and opportunities. Ther Deliv. 2017 Jul;8(8):647-661. doi: 10.4155/tde-2017-0037. PMID: 28730933.

- Murgia X, Loretz B, Hartwig O, Hittinger M, Lehr CM. The role of mucus on drug transport and its potential to affect therapeutic outcomes. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2018 Jan 15;124:82-97. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.10.009. Epub 2017 Oct 26. PMID: 29106910.

- Franks TJ, Colby TV, Travis WD, Tuder RM, Reynolds HY, Brody AR, Cardoso WV, Crystal RG, Drake CJ, Engelhardt J, Frid M, Herzog E, Mason R, Phan SH, Randell SH, Rose MC, Stevens T, Serge J, Sunday ME, Voynow JA, Weinstein BM, Whitsett J, Williams MC. Resident cellular components of the human lung: current knowledge and goals for research on cell phenotyping and function. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008 Sep 15;5(7):763-6. doi: 10.1513/pats.200803-025HR. PMID: 18757314

- Kim SM, Faix PH, Schnitzer JE. Overcoming key biological barriers to cancer drug delivery and efficacy. J Control Release. 2017 Dec 10;267:15-30. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.09.016. Epub 2017 Sep 14. PMID: 28917530; PMCID: PMC8756776.

- Verma S, Miles D, Gianni L, Krop IE, Welslau M, Baselga J, Pegram M, Oh DY, Diéras V, Guardino E, Fang L, Lu MW, Olsen S, Blackwell K; EMILIA Study Group. Trastuzumab emtansine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012 Nov 8;367(19):1783-91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209124. Epub 2012 Oct 1. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2013 Jun 20;368(25):2442. PMID: 23020162; PMCID: PMC5125250.

- Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, O'Callaghan CJ, Tu D, Tebbutt NC, Simes RJ, Chalchal H, Shapiro JD, Robitaille S, Price TJ, Shepherd L, Au HJ, Langer C, Moore MJ, Zalcberg JR. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008 Oct 23;359(17):1757-65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. PMID: 18946061.

- Schadendorf D, Hodi FS, Robert C, Weber JS, Margolin K, Hamid O, Patt D, Chen TT, Berman DM, Wolchok JD. Pooled Analysis of Long-Term Survival Data From Phase II and Phase III Trials of Ipilimumab in Unresectable or Metastatic Melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Jun 10;33(17):1889-94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2736. Epub 2015 Feb 9. PMID: 25667295; PMCID: PMC5089162

- Fehrenbacher L, Spira A, Ballinger M, Kowanetz M, Vansteenkiste J, Mazieres J, Park K, Smith D, Artal-Cortes A, Lewanski C, Braiteh F, Waterkamp D, He P, Zou W, Chen DS, Yi J, Sandler A, Rittmeyer A; POPLAR Study Group. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel for patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (POPLAR): a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016 Apr 30;387(10030):1837-46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00587-0. Epub 2016 Mar 10. PMID: 26970723.

- Le Tourneau C, Delord JP, Gonçalves A, Gavoille C, Dubot C, Isambert N, Campone M, Trédan O, Massiani MA, Mauborgne C, Armanet S, Servant N, Bièche I, Bernard V, Gentien D, Jezequel P, Attignon V, Boyault S, Vincent-Salomon A, Servois V, Sablin MP, Kamal M, Paoletti X; SHIVA investigators. Molecularly targeted therapy based on tumour molecular profiling versus conventional therapy for advanced cancer (SHIVA): a multicentre, open-label, proof-of-concept, randomised, controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015 Oct;16(13):1324-34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00188-6. Epub 2015 Sep 3. PMID: 26342236.

- Friedman AA, Letai A, Fisher DE, Flaherty KT. Precision medicine for cancer with next-generation functional diagnostics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015 Dec;15(12):747-56. doi: 10.1038/nrc4015. Epub 2015 Nov 5. PMID: 26536825; PMCID: PMC4970460.

- Arnedos M, Vicier C, Loi S, Lefebvre C, Michiels S, Bonnefoi H, Andre F. Precision medicine for metastatic breast cancer--limitations and solutions. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015 Dec;12(12):693-704. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.123. Epub 2015 Jul 21. PMID: 26196250.

- Larson SM, Carrasquillo JA, Cheung NK, Press OW. Radioimmunotherapy of human tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015 Jun;15(6):347-60. doi: 10.1038/nrc3925. Erratum in: Nat Rev Cancer. 2015 Aug;15(8):509. PMID: 25998714; PMCID: PMC4798425.

- Holohan C, Van Schaeybroeck S, Longley DB, Johnston PG. Cancer drug resistance: an evolving paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013 Oct;13(10):714-26. doi: 10.1038/nrc3599. PMID: 24060863.

- Hawkins JE Jr. Comparative otopathology: aging, noise, and ototoxic drugs. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 1973;20:125-41. doi: 10.1159/000393093. PMID: 4710505.

- Sakagami M, Sano M, Matsunaga T. Ultrastructural study of the effect of acute hypertension on the stria vascularis and spiral ligament. Acta Otolaryngol. 1984 Jan-Feb;97(1-2):53-61. doi: 10.3109/00016488409130964. PMID: 6196934.

- Sun W, Wang W. Advances in research on labyrinth membranous barriers. J Otol. 2015 Sep;10(3):99-104. doi: 10.1016/j.joto.2015.11.003. Epub 2015 Dec 1. PMID: 29937790; PMCID: PMC6002577.

- Ribatti D. The discovery of the blood-thymus barrier. Immunol Lett. 2015 Dec;168(2):325-8. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2015.10.014. Epub 2015 Oct 29. PMID: 26522647.

- Mikaelsson MA, Constância M, Dent CL, Wilkinson LS, Humby T. Placental programming of anxiety in adulthood revealed by Igf2-null models. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2311. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3311. PMID: 23921428.

- Genbacev O, Zhou Y, Ludlow JW, Fisher SJ. Regulation of human placental development by oxygen tension. Science. 1997 Sep 12;277(5332):1669-72. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1669. PMID: 9287221.

- Wood CE, Keller-Wood M. The critical importance of the fetal hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. F1000Res. 2016 Jan 28;5:F1000 Faculty Rev-115. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7224.1. PMID: 26918188; PMCID: PMC4755437.

- Condon JC, Jeyasuria P, Faust JM, Mendelson CR. Surfactant protein secreted by the maturing mouse fetal lung acts as a hormone that signals the initiation of parturition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Apr 6;101(14):4978-83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401124101. Epub 2004 Mar 25. PMID: 15044702; PMCID: PMC387359.

- Gao L, Rabbitt EH, Condon JC, Renthal NE, Johnston JM, Mitsche MA, Chambon P, Xu J, O'Malley BW, Mendelson CR. Steroid receptor coactivators 1 and 2 mediate fetal-to-maternal signaling that initiates parturition. J Clin Invest. 2015 Jul 1;125(7):2808-24. doi: 10.1172/JCI78544. Epub 2015 Jun 22. PMID: 26098214; PMCID: PMC4563678.

- Alsat E, Guibourdenche J, Couturier A, Evain-Brion D. Physiological role of human placental growth hormone. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998 May 25;140(1-2):121-7. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00040-9. PMID: 972217

- Thomson AJ, Telfer JF, Young A, Campbell S, Stewart CJ, Cameron IT, Greer IA, Norman JE. Leukocytes infiltrate the myometrium during human parturition: further evidence that labour is an inflammatory process. Hum Reprod. 1999 Jan;14(1):229-36. PMID: 10374126.

- Dudley DJ, Edwin SS, Mitchell MD. Macrophage inflammatory protein-I alpha regulates prostaglandin E2 and interleukin-6 production by human gestational tissues in vitro. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 1996 Jan-Feb;3(1):12-6. doi: 10.1016/1071-5576(95)00042-9. PMID: 8796800.

- Mesiano S, Chan EC, Fitter JT, Kwek K, Yeo G, Smith R. Progesterone withdrawal and estrogen activation in human parturition are coordinated by progesterone receptor A expression in the myometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002 Jun;87(6):2924-30. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.6.8609. PMID: 12050275.

- Merlino AA, Welsh TN, Tan H, Yi LJ, Cannon V, Mercer BM, Mesiano S. Nuclear progesterone receptors in the human pregnancy myometrium: evidence that parturition involves functional progesterone withdrawal mediated by increased expression of progesterone receptor-A. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007 May;92(5):1927-33. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0077. Epub 2007 Mar 6. PMID: 17341556.

- Smith R. Parturition. N Engl J Med. 2007 Jan 18;356(3):271-83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra061360. PMID: 17229954.

- Challis JR, Bloomfield FH, Bocking AD, Casciani V, Chisaka H, Connor K, Dong X, Gluckman P, Harding JE, Johnstone J, Li W, Lye S, Okamura K, Premyslova M. Fetal signals and parturition. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2005 Dec;31(6):492-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2005.00342.x. PMID: 16343248.

- Thornton DJ, Rousseau K, McGuckin MA. Structure and function of the polymeric in airway mucus.Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:459-86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100702. PMID: 17850213.

- Lässer C, Jang SC, Lötvall J. Subpopulations of extracellular vesicles and their therapeutic potential. Mol Aspects Med. 2018 Apr;60:1-14. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2018.02.002. Epub 2018 Feb 16. PMID: 29432782.

- Tang S, Zheng J. Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles: Structural Effects. Adv Healthc Mater. 2018 Jul;7(13):e1701503. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201701503. Pub 2018 May 29. PMID: 29808627.

- Chithrani BD, Ghazani AA, Chan WC. Determining the size and shape dependence of gold nanoparticle uptake into mammalian cells. Nano Letts. 2006 Apr;6(4):662-8. doi: 10.1021/nl052396o. PMID: 16608261.

- Wu L, Shan W, Zhang Z, Huang Y. Engineering nanomaterials to overcome the mucosal barrier by modulating surface properties. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2018 Jan 15;124:150-163. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.10.001. Epub 2017 Oct 5. PMID: 28989056.

- Walsh LA, Allen JL, Desai TA. Nanotopography applications in drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2015;12(12):1823-7. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2015.1103734. Epub 2015 Oct 29. PMID: 26512871; PMCID: PMC4839586.

- Ahadian S, Finbloom JA, Mofidfar M, Diltemiz SE, Nasrollahi F, Davoodi E, Hosseini V, Mylonaki I, Sangabathuni S, Montazerian H, Fetah K, Nasiri R, Dokmeci MR, Stevens MM, Desai TA, Khademhosseini A. Micro and nanoscale technologies in oral drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020;157:37-62. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.07.012. Epub 2020 Jul 22. PMID: 32707147; PMCID: PMC7374157.

- Medina-Sánchez M, Xu H, Schmidt OG, Micro- and nano-motors: The new generation of drug carriers, Ther. Deliv. 9 (2018) 303–316, 10.4155/tde-2017-0113. [PubMed: 29540126]

- González-Mariscal L, Nava P, Hernández S. Critical role of tight junctions in drug delivery across epithelial and endothelial cell layers. J Membr Biol. 2005 Sep;207(2):55-68. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0807-y. PMID: 16477528.

- Bisht R, Mandal A, Jaiswal JK, Rupenthal ID. Nanocarrier mediated retinal drug delivery: overcoming ocular barriers to treat posterior eye diseases. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2018 Mar;10(2). doi: 10.1002/wnan.1473. Epub 2017 Apr 20. PMID: 28425224.

- Witten J, Ribbeck K. The particle in the spider's web: transport through biological hydrogels. Nanoscale. 2017 Jun 22;9(24):8080-8095. doi: 10.1039/c6nr09736g. PMID: 28580973; PMCID: PMC5841163.

- Witten J, Samad T, Ribbeck K. Selective permeability of mucus barriers. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2018 Aug;52:124-133. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2018.03.010. Epub 2018 Apr 16. PMID: 29674157; PMCID: PMC7132988.

- Sridharan R, Cameron AR, Kelly DJ, Kearney CJ, O’Brien FJ, Biomaterial based modulation of macrophage polarization: A review and suggested design principles, Mater. Today. 18 (2015) 313–325, doi10.1016/j.mattod.2015.01.019.

- Gustafson HH, Holt-Casper D, Grainger DW, Ghandehari H. Nanoparticle Uptake: The Phagocyte Problem. Nano Today. 2015 Aug;10(4):487-510. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2015.06.006. Epub 2015 Sep 5. PMID: 26640510; PMCID: PMC4666556.

Shruti Tugnotia*

Shruti Tugnotia*

Dr. Neeraj Bhandari

Dr. Neeraj Bhandari

Aman Sharma

Aman Sharma

Ajay Kumar

Ajay Kumar

10.5281/zenodo.14709639

10.5281/zenodo.14709639