Abstract

The deposition of misfolded and neurotoxic forms of tau protein in particular regions of the cortex, basal ganglia, and midbrain causes progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), a neurodegenerative disease. It is among the most typical types of tauopathy. Concurrent neurodegenerative illnesses frequently occur alongside PSP, which manifests in a variety of phenotypic variants. PSP is always fatal, and there are currently no proven effective disease-modifying treatments for it. Numerous tau-targeting therapeutic approaches have been studied and shown to be ineffective, including vaccinations, monoclonal antibodies, and microtubule-stabilizing drugs. There is an urgent need to treat PSP and other tauopathies, and numerous clinical trials looking into tau-targeted therapies are currently under progress. To gather data for this study, preclinical and clinical research on PSP treatment was retrieved from the PubMed database. In order to find previous and ongoing clinical trials pertinent to the treatment of PSP, a search was also conducted on the ClinicalTrials.-gov website of the US National Library of Medicine. Our findings on these papers, which cover possible disease-modifying medication trials, modifiable risk factor management, and symptom treatments, are compiled in this narrative review.

Keywords

Steele–Richardson–Olszewski disease; antidepressants; shy dragger syndrome.

Introduction

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is an uncommon neurological disorder that affects movement, gait, balance, speech, swallowing, vision, eye movements, mood, behavior, and cognition. Steele, Richardson, and Olszewski described the syndrome in 1964 as an unusual constellation of supranuclear gaze palsy, progressive axial rigidity, pseudobulbar palsy, and mild dementia.[1]A subset of progressive neurodegenerative diseases that exhibit symptoms of Parkinson’s disease are known as atypical Parkinsonian syndromes. These neurodegenerative diseases are brought on by protein deposits in brain tissue, just like Parkinson’s disease. Although the exact cause of these protein deposits is unknown, senior age is thought to be a contributing factor.[2]The buildup of tau protein in various brain regions is linked to the phenotypic variability of PSP, a 4-repeat tauopathy. However, PSP may have clinical similarities to a wide range of other illnesses. There are no reliable in vivo investigations of PSP-mimicking disorders or uncommon PSP characteristics. An overview and differential diagnosis of various illnesses are provided in this study.[3]

![Progressive Supranuclear palsy . [18].png](https://www.ijpsjournal.com/uploads/createUrl/createUrl-20241128154051-4.png)

Fig 1: Progressive Supranuclear palsy . [18]

Background of PSP :-

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) was first identified as a clinicopathological syndrome in 1964 by Drs. Steele, Richardson, and Olszewski. They described a number of patients who had dementia, facial and cervical dystonia, ocular motor abnormalities, postural instability, and other symptoms. [4] PSP is classified as a neuropathological illness. The 1996 publication of clinical diagnostic criteria for PSP by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/Society for PSP has a high specificity but a low sensitivity for variant PSP syndromes that present differently from Richardson’s syndrome..[5]We know very little about falls, and there aren’t many good treatment choices, even though falls are a nearly ubiquitous clinical feature and a key component of the presentation and diagnostic criteria of progressive supranuclear palsy..[6]Nine MSA event cases and sixteen PSP incident cases were discovered during the study’s 15-year duration. PSP and MSA instances did not begin until the age of fifty. Between the ages of 50 and 99, the average yearly incidence rate (new cases per 100,000 person-years) for MSA was 3.0 and for PSP it was 5.3. The prevalence of PSP was continuously greater in men and rose sharply with age, from 1.7 at 50 to 59 to 14.7 at 80 to 99. [7]The Movement Disorders Society proposed clinical diagnostic criteria in 2017 to identify these discrete clinical subtypes as PSP-RS, PSP-P, PSP with corticobasal syndrome (PSP-CBS), PSP with progressive gait freezing (PSP-PGF), PSP with predominant ocular motor dysfunction (PSP-OM), PSP with predominant frontal presentation (PSP-F), PSP with predominant positural instability (PSP-PI), or PSP with predominant speech and language disorder (PSP-SL). [8]

Diagnosis of PSP

Patients with PSP are usually three years past the onset of their initial symptoms when they are diagnosed. One That marks the halfway point of the disease. There are several reasons for the delayed diagnosis, including misdiagnosis as depression and/or Parkinson’s disease, failure to recognize the importance of early symptoms, and delays in obtaining guidance from general practitioners. The phrase “atypical Parkinsonism” is one of the issues. Nothing about PSP is “atypical”; rather, it is typical of the condition and easily differentiated from Parkinson’s disease. PSP is the exact opposite of Parkinson’s disease in every way. For instance, the limb symptoms are symmetrical, free of tremor, and rigidity is noticeable in the trunk and neck and negligible in the periphery.[9] A small number of recent studies found likely characteristics that set PSP apart from Parkinson’s disease. Patients with PSP and early-stage Parkinson’s disease (PD) have diverse gait patterns, which suggests that their underlying pathophysiological processes are different. PSP patients had a prolonged gait cycle, decreased step and cycle length, and decreased cadence and velocity. Additionally, a small number of clinical manifestations differ from Parkinson disease [10,11]. PSP patients exhibit axial rigidity, which is only observed in the trunk and neck, symmetrical limb signals, no tremor, and reduced rigidity in the periphery. [12] To further narrow down the diagnosis, imaging examinations and laboratory tests can be utilized to rule out additional illnesses [13]

Epidemiology Of PSP :-

PSP incidence and prevalence. Over the past few decades, estimates of PSP prevalence have risen from 1.39/100,000 to 17.9/100,000. The variation in prevalence estimates is probably caused by variations in study population, methodology, diagnostic criteria, and diagnostic knowledge. After age 60, the incidence of PSP increases to 0.9–1.9/100,000, Geographical clusters have been found in PSP, which is intriguing since it suggests that environmental factors may play a role in PSP. Male preponderance was identified as a distinctive characteristic of PSP in previous research.8, 16, and 17 In other recent research, PSP was more common in males than in women. Moreover, in cases with clinical confirmation, sex variations in PSP were evident.We discovered a male preponderance in PSP when we examined the findings of twelve investigations from autopsy-confirmed PSP cases. The outcomes of pathological research may be impacted by selection bias, so such findings should be evaluated cautiously. No comparable preponderance was seen in other research. Some even claimed that women were more likely to get it. Thus, it is still unknown if men are more affected by PSP than women.[14]A surprising 75% of people in the French Caribbean island of Guadeloupe had atypical parkinsonism that is not responsive to levodopa; only 25% of them met the Brain Bank criteria for Parkinson’s disease.16 Oculomotor abnormalities, postural instability with falls, and a PSP-like syndrome were present in half of the individuals with atypical parkinsonism. But only a tiny percentage met the requirements for PSP, while the bulk deviated from traditional PSP due to the occurrence of hallucinations (unrelated to . [15]

•The most common first signs of PSP include:

- A loss of balance when walking or climbing stairs. This often involves falling, especially falling backward.

- Difficulty looking downward with your eyes.

- A wide-eyed staring expression.Other symptoms of PSP include:

• Difficulty swallowing.

- Stiff muscles that affect mobility (your ability to move).

- Difficulty speaking. Your speech might be quieter and slurred, making it hard to pronounce words.

- Mood changes, such as depression, apathy (loss of interest) and irritability.

- Personality changes.

- Changes in behavior, such as impulsivity and poor judgment.

- Dementia.

- Insomnia.

- REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD). Sensitivity to bright light (photophobia). [16]

![Symptoms of Progressive Suprqnuclear palsy. [17].png](https://www.ijpsjournal.com/uploads/createUrl/createUrl-20241128154051-3.png)

Fig 2 : Symptoms of Progressive Suprqnuclear palsy. [17]

Causes of PSP:

PSP happens when a protein called tau accumulates in specific brain regions, damaging the brain cells there.

The brain naturally contains tau, which is typically broken down before it reaches significant levels.

It isn’t adequately broken down in PSP patients, and it accumulates in brain cells in dangerous clumps.

Both the quantity and location of these aggregates of aberrant tau in the brain can differ across PSP patients.

This implies that a variety of symptoms may be present with the illness. [19]

Pathology :

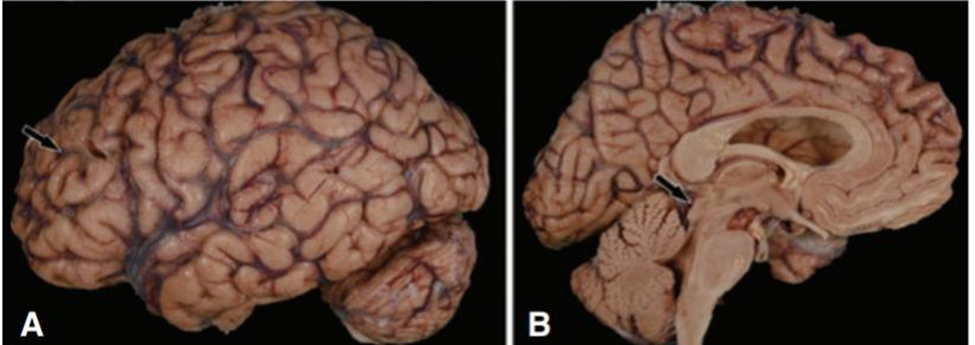

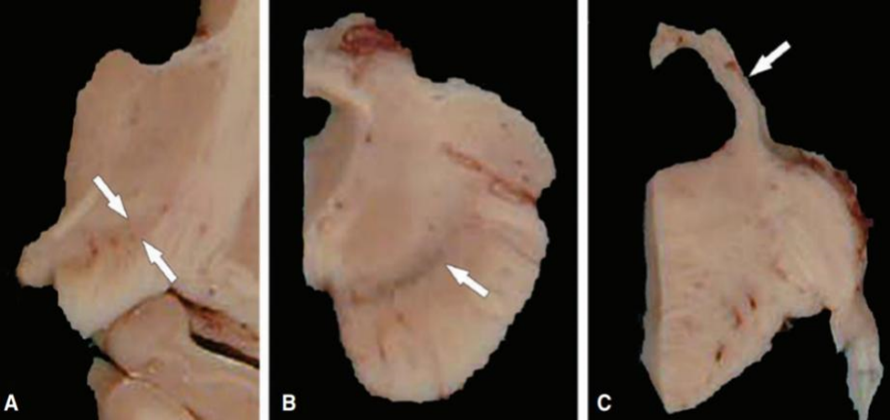

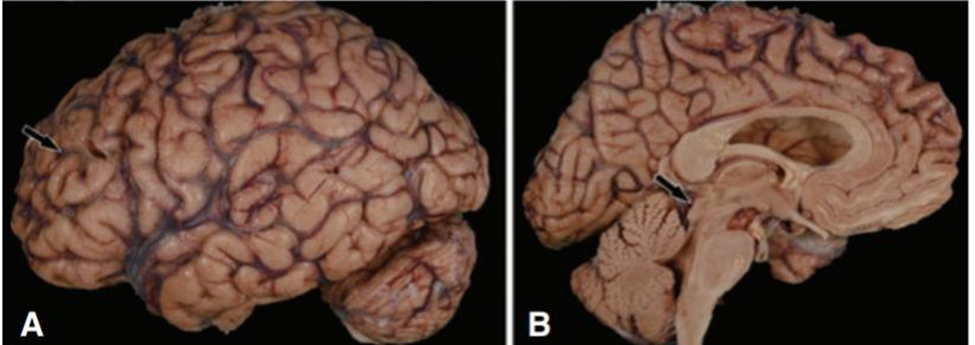

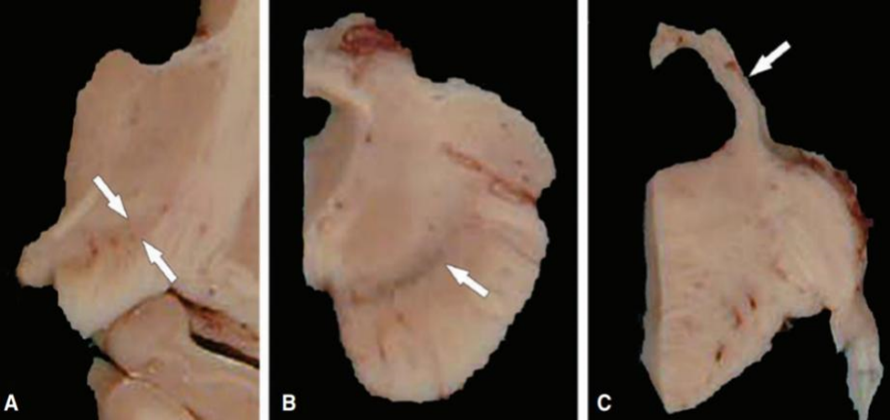

Macroscopic Pathology :. When the brain is grossly examined in PSP, unique characteristics are frequently found. The majority of cases exhibit modest frontal atrophy, which may affect the pre-central gyrus, but the total weight of the brain (1170 ± 150 g) may be within normal ranges. The midbrain exhibits atrophy, particularly in the tectum and, to a lesser degree, the pons. (Fig 3 )The Sylvius aqueduct and third vein may be dilated. The locus ceruleus is frequently better preserved, whereas the substantia nigra exhibits loss of pigmentation. The subthalamic nucleus is smaller than anticipated and could be discolored gray. The hilus of the cerebellar dentate nucleus and the superior cerebellar poduncle are often atrophic (90) and gray in color as a result of myelinated fiber loss. ( Fig :4)

Microscopic Pathology: Microscopic observations include gliosis, neuronal loss, and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) that impact the brainstem, diencephalon, and basal ganglia. The subthalamic nucleus, the globus pallidus, and the substantia nigra are the nuclei most impacted. The pathological distribution is seen in Table 1. Although lesions are prevalent in the peri-Romalic region, the cerebral cortex is comparatively unaffected. Unless argyrophilic grain disease is present concurrently, which happens in around 20% of patients, the limbic lobe is maintained in PSP . Particularly in the ventral anterior and lateral thalamic nuclei, the striatum and thalamus frequently exhibit some degree of neuronal loss and gliosis. There is often a slight decrease of cells in the Meynert basal nucleus . [20]

Fig 3 : Gross appearance of the brain in progressive supranuclear palsy shows mild frontal atroph A)With widening of sulcal spaces (arrows); on medial views (B) the most consistent finding is atrophy of the midbrain with flattening of the tectal plate (arrow).[20]

Fig 4: Gross appearance of the sectioned brain reveals atrophy of the subthalamic nucleus (arrows) in the diencephalon at the level of the mammillotha-lamic tract (A), loss of pigment in the substantia nigra (arrow) in the midbrain (B), and atrophy of the superior cerebellar peduncle (arrow) in the rostral pons (C).[20]

![Stages of PSP [ 26].png](https://www.ijpsjournal.com/uploads/createUrl/createUrl-20241128154051-0.png)

Fig. 5: Stages of PSP [ 26]

- Early Stage :Early on, mobility and balance are the main symptoms, which may be modest. Occasional falls and mild visual and speech abnormalities are possible.

- Mid-Stage: Symptoms become increasingly severe and incapacitating as PSP progresses. As balance issues increase, walking becomes challenging and falls become more common. As anomalies in eye movement become more noticeable, eyesight is affected and the chance of accidents increases.

- Advanced stage: People with PSP need a lot of help with everyday tasks when they are in the advanced stage. Mobility deteriorates to the point where wheelchairs or other mobility aids are frequently required. Additionally, problems with speech and swallowing may get worse, necessitating particular assistance and interventions.

- End stage : People with PSP are usually immobile and reliant on caretakers for full care during the last stage. There may be significant cognitive deterioration and a severe lack of communication. Additional health decline may result from complications like pneumonia or other infections. [ 21]

Drug treatment in PSP :

Although PSP is currently incurable, therapy may be beneficial. Because every patient is unique, the following medications’ selection, timing, and dosages will differ from one individual to the next. With the exception of dopaminergic medication, the maxim should be “start low and go slow” because PSP makes people more susceptible to side effects, which can have serious repercussions in situations when their health is poor or their social standing is shaky. [22]

• Non-Disease-Modifying Treatmen

PSP is still a disease that kills people everywhere, even after decades of medication studies. Levodopa medication occasionally produced early advantages for patients with the PSP-P or PSP-RS phenotypic subgroups, particularly for those with bradykinesia and stiffness. Nevertheless, this advantage was frequently fleeting and had no bearing on the course of the illness as a whole.At the moment, the majority of treatments are symptomatic, and a number of non-disease-modifying therapies are undergoing clinical trials.

• Transcranial and Deep Brain Stimulation

Transcranial and deep brain stimulation’s effectiveness on PSP progression has been assessed in a number of clinical investigations. There has been no report of the findings of a 2014 clinical trial (NCT01174771) that assessed the safety and effectiveness of noninvasive cortical stimulation for the treatment of PSP and CBD. An additional clinical trial (NCT02734485) aimed to assess the effectiveness of deep transcranial magnetic stimulation across the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and left Broca area in facilitating the recovery of motor and cognitive function in PSP patients. This study’s most recent update was published in 2016, and no findings have been released since then. [23]Other therapies, such sirolimus, a mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor that triggers autophagy, failed after 48 weeks of therapy. According to a natural history study, low vitamin B12 levels (< 367>

CONCLUSION

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), also known as Richardson’s syndrome, is a complex and debilitating neurodegenerative disorder. Despite significant advances in our understanding of the disease, PSP remains a challenging condition to diagnose and treat. This review has highlighted the current state of knowledge on PSP, including its clinical features, pathophysiology, genetics, and treatment options.While current treatments for PSP are largely symptomatic and offer limited benefit, ongoing research into the disease’s underlying biology and novel therapeutic targets offers hope for the development of more effective treatments in the future. Further studies are needed to elucidate the complex interplay between tau pathology, neuroinflammation, and neurodegeneration in PSP, and to translate this knowledge into innovative and effective therapeutic strategies. Ultimately, a comprehensive understanding of PSP will require continued advances in basic, translational, and clinical research. By fostering collaboration and knowledge-sharing among researchers, clinicians, and patients, we can accelerate progress towards improved diagnosis, treatment, and care for individuals affected by this devastating disease.

REFERENCES

- Steele Jc, Richardson Jc, Olszewski J. Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. A Heterogeneous Degeneration Involving The Brain Stem, Basal Ganglia And Cerebellum With Vertical Gaze And Pseudobulbar Palsy, Nuchal Dystonia And Dementia. Arch Neurol. 1964 Apr;10:333-59

- Golbe Li, Davis Ph, Schoenberg Bs, Duvoisin Rc. Prevalence And Natural History Of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy.Neurology 1988;38(7):1031–4. Doi:10.1212/Wnl.38.7.103.

- Rösler, T. W., Tayaranian Marvian, A., Brendel, M., Nykänen, N. P., Höllerhage,M., Schwarz, S. C., Et Al. (2019). Four-Repeat Tauopathies. Prog. Neurobiol.180:101644. Doi: 10.1016/J.Pneurobio.2019.101644

- David G Coughlin, Md Mstr1, Irene Litvan, Md Msc1,* Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: Advances In Diagnosis And Management. 2020 April ; 73: 105–116. Doi:10.1016/J.Parkreldis.2020.04.014.

- Gesine Respondek Md , Maria Stamelou Md, Carolin Kurz Md,Keith A. Josephs Md, Mst, Msc, Clinical Diagnosis Of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: The Movement Disorder Society Criteria. First Published: 03 May 2017 Https://Doi.Org/10.1002/Mds.26987 Citations: 1,465

- Fraser S. Brown Bmedsci(Hons), Mb, Cb, James B. Rowe Md, Phd,Luca Passamonti Md, Timothy Rittman Bmbs, Bmedsci(Hons), Pgcertmeded, Mrcp, Phd.Falls In Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. First Published: 06 December 2019 Https://Doi.Org/10.1002/Mdc3.12879 .Citations: 21

- James H. Bower, Md, Demetrius M. Maraganore, Md, Shannon K. Mcdonnell, Ms, Walter A. Rocca, Md, Mph. Incidence Of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy And Multiple System Atrophy In Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976 To 1990.November 1997 Issuse Https://Doi.Org/10.1212/Wnl.49.5.128

- Kovacs Gg, Lukic Mj, Irwin Dj, Arzberger T, Respondek G, Lee Eb, Coughlin D, Giese A, Grossman M, Kurz C, Mcmillan Ct, Gelpi E, Compta Y, Van Swieten Jc, Laat Ld, Troakes C, Al-Sarraj S, Robinson Jl, Roeber S, Xie Sx, Lee Vm, Trojanowski Jq, Höglinger Gu. Distribution Patterns Of Tau Pathology In Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. Acta Neuropathol. 2020 Aug;140(2):99-119. Doi: 10.1007/S00401-020-02158-2. Epub 2020 May 7. Pmid: 32383020; Pmcid: Pmc7360645.

- Coyle-Gilchrist Its, Dick Km, Patterson K, Et Al. Prevalence, Characteristics, And Survival Of Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration Syndromes. Neurology 2016;86:1736–43.

- Amboni M, Ricciardi C, Picillo M, De Santis C, Ricciardelli G, Abate F, Barone P. Gait Analysis May Distinguish Progressive Supranuclear Palsy And Parkinson Disease Since The Earliest Stages. Scientific Reports. 2021;11(1), 1-9.

- Raccagni C, Nonnekes J, Bloem Br,Peball M, Boehme C, Seppi K, Wenning Gk. Gait And Postural Disorders In Parkinsonism: A Clinical Approach. Journal Of Neurology. 2020;267(11):3169–3176. Avaialble:Https://Doi.Org/10.1007/S00415-019-09382-1

- Rowe Jb, Holland N, Rittman T. Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: Diagnosis And Management. Practical Neurology. 2021;21(5):376-383.

- Williams Dr, Lees Aj. Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: Clinicopathological Concepts And Diagnostic Challenges. The Lancet Neurology, 2009;8(3):270-279

- Hee Kyung Park,1,2 Sindana D. Ilango,3,4 Irene Litvan5. Review Articles, Environmental Risk Factors For Progressive Supranuclear Palsy.Https://Doi.Org/10.14802/Jmd.20173

- L. Donker Kaat, W.Z. Chiu, A.J.W. Boon And J.C. Van Swieten Current Alzheimer Res. 2011 May 1;8(3):295-302.Recent Advances In Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: A Review

- Https://Search.App?Link=Https://my.Clevelandclinic.Org/health/diseases/6096-Progressive-Supranuclear-Palsy&Utm_Campaign=Aga&Utm_Source=Agsadl1,sh/x/gs/m2/

- Https://Images.App.Goo.Gl/Wqe9yneum5tgoiwk

- James B Rowe,1,2 Negin Holland,1,3 Timothy Rittman1,3 .Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: Diagnosis And Management.Rowe Jb, Et Al. Pract Neurol 2021;21:376–383. Doi:10.1136/Practneurol-2020-002794

- Https://Search.App?Link=Https://www.Nhs.Uk/conditions/progressive-Supranuclear-Palsy-Psp/#:~:text=psp occurs when brain cells,harmful clumps in brain cells.&Utm_Campaign=Aga&Utm_Source=Agsadl1,sh/x/gs/m2/4

- Dickson Dw, Rademakers R, Hutton Ml. Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: Pathology And Genetics. Brain Pathol. 2007 Jan;17(1):74-82. Doi: 10.1111/J.1750-3639.2007.00054.X. Pmid: 17493041; Pmcid: Pmc8095545.

- About Dr. Entekhab Alam, Md (Hom.), Ph.D(S) Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (Psp): Symptoms, Stages, And Treatment.About.

- James B Rowe1,2, Negin Holland1,3, Timothy Rittman1,3,Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: Diagnosis And Management. Https://Doi.Org/10.1136/Practneurol-2020-002794

- Elise E. Dunning . Boris Decourt . Nasser H. Zawia . Holly A. Shill .Marwan N. Sabbaghpharmacotherapies For The Treatment Of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: A Narrative Review. Neurol Ther (2024) 13:975–1013 .Https://Doi.Org/10.1007/S40120-024-00614-9

- Watanabe H, Shima S, Mizutani Y, Ueda A, Ito M. Multiple System Atrophy: Advances In Diagnosis And Therapy. J Mov Disord. 2023 Jan;16(1):13-21. Doi: 10.14802/Jmd.22082. Epub 2022 Dec 20. Pmid: 36537066; Pmcid: Pmc9978260.

- Brent Bluett,Alexander Y. Pantelyat3†Irene Litvanirene Litvan4farwa Alifarwa Ali5diana Apetauerovadiana Apetauerova6danny Begadanny Bega7lisa Bloomlisa Bloom8james Bowerjames Bower5adam L. Boxeradam L. Boxer9marian L. Dalemarian L. Dale10rohit Dhallrohit Dhall11antoine Duquetteantoine Duquette12hubert H. Fernandezhubert H. Fernandez13jori E. Fleisherjori E. Fleisher14murray Grossmanmurray Grossman15michael Howellmichael Howell16diana R. Kerwindiana R. Kerwin. Best Practices In The Clinical Management Of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy And Corticobasal Syndrome: A Consensus Statement Of The Curepsp Centers Of Care . Published: 01 July 2021 Doi: 10.3389/Fneur.2021.694872

- Fig5:Https://Images.App.Goo.Gl/Dsvav3tt2mfkglnh7

Jaysing Patil * 1

Jaysing Patil * 1

Chopade Babasaheb 2

Chopade Babasaheb 2

![Progressive Supranuclear palsy . [18].png](https://www.ijpsjournal.com/uploads/createUrl/createUrl-20241128154051-4.png)

![Symptoms of Progressive Suprqnuclear palsy. [17].png](https://www.ijpsjournal.com/uploads/createUrl/createUrl-20241128154051-3.png)

![Stages of PSP [ 26].png](https://www.ijpsjournal.com/uploads/createUrl/createUrl-20241128154051-0.png)

10.5281/zenodo.14234935

10.5281/zenodo.14234935