Abstract

Drug repurposing (DR) is a novel strategy to drug discovery that aims to uncover new applications for existing drugs. This technique is gaining popularity because to its cost-effectiveness and capacity to speed up the development process by employing molecules with proven pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. In recent years, pharmaceutical companies have increasingly turned to DR, particularly for complicated disorders such as Parkinson's disease (PD). However, DR has significant problems in PD, such as illness complexity, diagnostic difficulty, regulatory impediments, and patient variety. The multidimensional nature of PD, which includes hereditary, environmental, and biological components, makes it challenging to create effective treatments. Misdiagnosis of PD and atypical parkinsonism syndromes hinders treatment. Regulatory difficulties and the short patent life of repurposed pharmaceuticals diminish pharmaceutical companies' incentives to invest in DR. The need for additional study into the underlying causes of PD, combined with problems in clinical trials and access to neurological services, and stymies progress. To address these problems, governments, foundations, and the pharmaceutical sector must collaborate on novel development paths, regulatory incentives, and drug repurposing for Parkinson's disease and other neurodegenerative disorders.

Keywords

Drug repurposing, Complexity, Genetic factor, Parkinson disease, Regulatory hurdles

Introduction

The practice of finding new uses for currently available drugs is known as drug repurposing (DR), and it is thought to be an effective and economical strategy [1]. Other names for it include pharmaceutical redirection, drug rescue, drug recycling, repositioning, re-profiling, re-tasking, and therapeutic switching. The process of finding new pharmacological indications from old, existing, unsuccessful, investigative, previously marketed, FDA-approved, or pro-drugs is how it is defined [2]. It has been proposed that 75% of currently prescribed drugs may be used to treat different illnesses [1]. Using the medicines repositioning strategy in drug research and development programs, many pharmaceutical companies have been producing new treatments with the discovery of novel biological targets in recent years [2].Repurposing existing medications for the treatment of various medical conditions has become increasingly popular, as it allows the drug development process to be completed more quickly and cost-effectively. This is achieved by using de-risked compounds with established preclinical, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic profiles, enabling them to advance directly into phase III or IV clinical trials [3].Repurposing a drug means applying it to a new therapeutic use after approval from regulatory agencies such as the FDA, EMA, or MHRA. Many pharmaceutical companies are now actively pursuing drug repurposing to revive previously unsuccessful FDA-approved compounds for treating various diseases [4].

Challenges in drug repurposing for PD:

The process of developing disease-modifying treatments is typically time-consuming, costly, and extremely dangerous, taking an average of 13 to 15 years and an estimated 2.6 billion USD to bring a new chemical to market. Furthermore, the market success rate of medications during clinical trials is less than 10% [5]. Repurposed medications can stray from the original safety testing and development stage, but in order to prove their effectiveness, they must undergo extensive, high-risk, and costly clinical trials. Clinical trials may take a lengthy time due to the slow course of neurodegenerative illnesses. Furthermore, in addition to demonstrating drug penetration into the brain, medications are frequently examined for safety issues in geriatric populations that have comorbidities and receive treatment that may interact with the repurposed drug. DR may be problematic in neuropathological situations due to complicated molecular and cellular communication processes. The fact that medications respond to several targets while affecting a single target may increase the likelihood of a variety of undesirable responses. An all-inclusive review of the assets, as well as the absence of these undesirable effects, can help us understand pharmacological repositioning from a more multidimensional perspective [6]. Research on DR has a number of obstacles and constraints. Despite receiving hundreds of drug candidate submissions annually, the FDA approved an average of just 41 treatments between 2010 and 2018. The thorough evaluation required to guarantee the safety and efficacy of medication candidates is mostly to blame for this high attrition rate and sluggish approval procedure. A significant obstacle to DR investigations is the scarcity of new pharmaceuticals available for repurposing approval of new medications occurs on an annual basis. Furthermore, the decreased effectiveness of repurposed medications combined with patent and regulatory concerns makes pharmaceutical repurposing less successful [7].

The main challenges include:

- Complexity of Parkinson’s disease

- Challenges in Diagnosis of disease

- Regulatory hurdles

- Patient diversity

Complexity of PD:

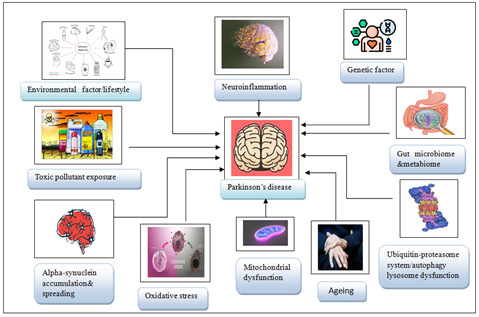

Since the earliest report of PD in Western medicine over two centuries ago, tremendous progress has been achieved in understanding, diagnosing, and treating the condition. Despite these advances and years of research in the subject of PD, our understanding of its biological foundation is still limited. Several ideas about the pathobiology of PD have emerged and evolved over time, with the general view being that the disease is complicated, with multiple elements many of which are still unknown contributing to disease manifestation and development. To present, the vast bulk of PD research has been undertaken with the idea that PD is a single disease. More research should focus on the study and identification of protective and compensatory mechanisms, counteracting the development of PD. The concept of PD as a single disease should The etiology of PD is unknown, although the disease has been associated with several factors such as genetics head trauma air pollution, exposure to pesticides, prior infections, or alterations in the gut microbiota. Nonetheless, research has provided convincing evidence of the involvement of oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impaired proteostasis in the pathogenesis of several neurodegenerative diseases, including PD. In addition, neuroinflammation is increasingly recognized as having a significant contribution in neurodegeneration and may become a therapeutic target in

Figure 1: Key Factors Contributing to Parkinson’s Disease Onset

Genetic factor:

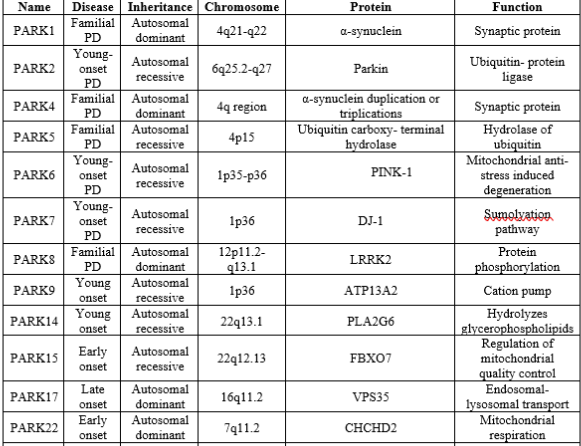

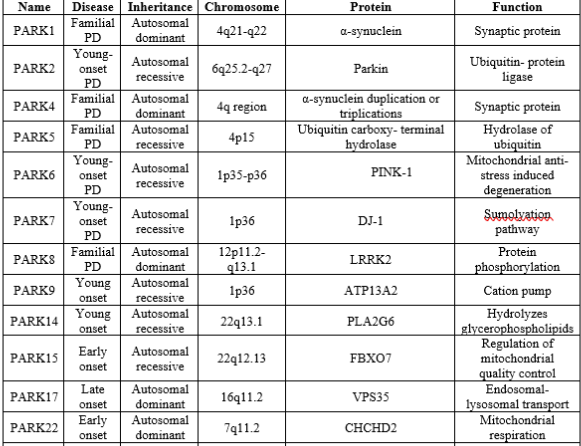

The first PD-associated gene, synuclein alpha (SNCA), was discovered in 1997. With the development of gene technologies and population studies, more than 20 genes have been discovered in monogenic forms of PD; these genes include SNCA, LRRK2, PARKIN, PINK1, and DJ-1. Some of these genes are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction given in table 1[9].

Table 1: List Of Parkinson’s Disease Causing Genes.

Challenges in Diagnosis of disease:

Diagnosing idiopathic PD can be a simple clinical exercise in cases with a classic history, characteristic asymmetric motor symptoms, no unusual findings, and the exclusion of other causes. However, in ordinary clinical practice, diagnostic misclassification is prevalent, with error rates ranging from 15% to 24% in different datasets. A recent meta-analysis indicated that the pooled diagnostic accuracy for the clinical diagnosis of PD was only 80.6?ross 11 clinicopathological studies. Despite the adoption of strong clinical diagnostic criteria, neurologists classified 10% of Parkinson's patients with alternative diseases. Misdiagnosis of non-Parkinson's tremor disorders, including essential tremor and various kinds of secondary parkinsonism, is a frequent occurrence in clinical practice. In the early stages, even movement disorder specialists frequently have difficulty telling PD apart from atypical parkinsonian illnesses. The term "atypical parkinsonism" describes a class of neurodegenerative disorders that have pronounced parkinsonian symptoms, but they differ from PD in terms of overall clinical presentation, underlying pathology, course, and prognosis. These syndromes include tauopathies like progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration, which are characterized by the deposition of four-repeat phosphorylated tau aggregates in neurons, and multiple system atrophy, which involves glial cytoplasmic inclusions of misfolded ?-synuclein in oligodendrocytes. At early stages of the disease, all three conditions can be very difficult to distinguish from PD, as well as from each other. Clinicopathological studies have revealed error rates in clinical diagnosis in 7–35% of cases. Clinical pointers that can inform the differential diagnosis between PD and these main types of atypical degenerative parkinsonism. These differentiating features can evolve over time and, particularly the parkinsonian variants of multiple system atrophy and progressive supranuclear palsy, can be notoriously difficult to distinguish from Parkinson’s disease in early disease stages-including asymmetry (which is particularly striking in corticobasal degeneration) and responsiveness to levodopa [9]. phosphorylated tau aggregates in neurons, and multiple system atrophy, which involves glial cytoplasmic inclusions of misfolded ?-synuclein in oligodendrocytes.and corticobasal degeneration, which are characterized by the deposition of four-repeat phosphorylated tau aggregates in neurons.

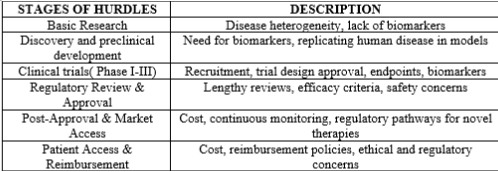

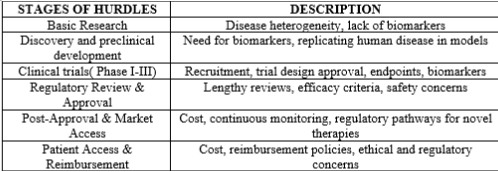

Regulatory hurdles:

FDA offers a period of 3 years exclusivity for a new use of a previously marketed drug for a new indication, this period is often too short to recoup investment and it does not prevent physicians from prescribing the existing drug “off-label” if dosages suitable for the new indication are already marketed or can safely be compounded from the marketed product. If generic versions are available, the challenges are even greater, since payers can promote a “generic switch” even if branded drugs have a new indication. Although such generic prescribing lowers costs for the patient and payer, it discourages companies from investing in clinical trials to prove drug efficacy because this approach limits pricing flexibility and the potential return from their risk investment. In addition, demonstrating the value of new treatments is of growing importance in the United States and globally. Payers, whether they are patients, private insurers, or governments want significant clinical benefit or an overall reduction in medical costs for the patient (i.e., “cost effectiveness”). This is required in some health systems. As an example, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) determines which drugs are covered under the National Health Service in England and it requires a mathematical calculation to determine the potential cost effectiveness and benefits to patients. If the threshold is not met, governmental reimbursement is not recommended. In the United States, private insurers factor total cost of care and value of the drug into their decision as to which drugs will be included in their plans for reimbursement. While the cost of the development path is lower with a repurposed drug, in the current pharmaceutical R&D context repurposing projects have very little chance to enter into the portfolios of established pharmaceutical companies. The price supported for a repurposed drug is no different than an entirely new drug and is ultimately based on its uniqueness/nonsubstitutability and its clinical and economic benefits. Thus, the value of repurposing from an industry perspective for currently marketed, branded, or generic drugs will often be marginal due to limited patent life. At the same time, most pharmaceutical companies are faced with more phase II clinical opportunities across a wide range of disease indications than their research and development (R&D) budgets can sustain. As a result, any new clinical stage R&D project inherently must displace another project that is in the portfolio, and repurposing projects with limited return on investment will likely be deprioritized. For approved drugs with potential benefit for neurodegenerative diseases, alternate development pathways are needed. Foundations and government may need to take the initiative either by advocating for policy changes to incentivize company investment or by directly funding repurposed drug development [10].

Table 2: Regulatory Hurdles In Parkinson’s Disease:

Patient diversity:

Epidemiological patterns are heavily dependent on the power of detection of disease, which is an interplay of diagnostic factors as well as the accuracy of determining the correct diagnosis in the general population. In the case of PD, the first and foremost factor in this is the availability of neurologists. For example On the African continent, there is a wide discrepancy in the number of neurologists and medical facilities between different countries. Some urban centers may have comprehensive neurological and auxiliary services available, consisting of neurologists, neurosurgeons, neurophysiologists, and related equipment such as electro-encephalography, electromyography, and nerve conduction studies. However, even in these centers, accessibility to such services by the general population is limited due to financial restrictions and barriers related to cultural perception of disease. Reviewing the situation in Africa as a whole, neurological services are either scarce or not available, as illustrated by a survey conducted in 2005 that included 11 countries that were entirely without neurological services. Currently, in most countries in Africa, there is still a dearth of neurologists, nurses, physiotherapists, and other allied professions due to limited training facilities for neurologists within Africa, as well as emigration of skilled personnel to more economically developed countries. Although, some research on the clinical and epidemiological aspect of PD has been conducted, genetics research of PD is limited in Africa, as a result of poor awareness and lack of facilities. The low number of scientific publications on PD mirrors the low density of neurological professionals. It also shows the problems with treatment strategies for PD in Africa. In this setting, after clinically diagnosing parkinsonism, drug treatment usually starts with a levodopa/carbidopa trial. Dopamine agonists are unavailable in the majority of African countries. Treatment can be called unsuccessful when about one gram of levodopa/carbidopa daily for a number of weeks does not elicit a significant treatment response. Practically however, the high cost of the treatment may necessitate patients to terminate this titration prematurely, or to reduce dosage frequency to once daily or very low dosages. There will be a proportion of patients who would have responded better had there been no financial limitations. Physiotherapy is also a useful treatment modality, but is best given in limited sessions due to long travel distances and low resources. Physiotherapy in lower income regions is aimed at education and low frequency follow up: patients and relatives may attend for a few days consecutively, perform home exercises and return a number of months later [11].

CONCLUSION:

Drug repurposing DR offers a cost-effective and faster approach to drug discovery, especially for complex diseases like PD. However, it faces significant obstacles, including the complexity of PD, diagnostic challenges, regulatory barriers, and limited incentives for pharmaceutical companies. Misdiagnosis and disparities in access to neurological care, especially in low-resource areas, further complicate the process. Addressing these issues through collaboration between governments, foundations, and the pharmaceutical industry is essential. With these efforts, DR can significantly improve treatments for PD and other neurodegenerative diseases, enhancing patient outcomes and scientific understanding.

REFERENCE

- Huang F, Zhang C, Liu Q, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Qin Y, et al. Identification of amitriptyline HCl, flavin adenine dinucleotide, azacitidine and calcitriol as repurposing drugs for influenza A H5N1 virus-induced lung injury. PLoS Pathog.2020;16(3):e1008341. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1008341.

- Mithun R, Shubham JK, Anil GJ. Drug Repurposing (DR): An Emerging Approach in Drug Discovery. Drug Repurposing. IntechOpen: Rijeka. 2020.

- Pushpakom S, Iorio F, Eyers PA, Escott KJ, Hopper S, Wells A, et al. Drug repurposing: progress, challenges and recommendations. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019 Jan;18(1):41–58. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2018.168.

- Parvathaneni V, Kulkarni NS, Muth A, Gupta V. Drug repurposing: a promising tool to accelerate the drug discovery process. Drug discovery today. 2019 Oct 1;24(10):2076-85.

- Agostini F, Masato A, Bubacco L, Bisaglia M. Metformin repurposing for Parkinson disease therapy: opportunities and challenges. International journal of molecular sciences. 2021 Dec 30;23(1):398.

- Kakoti BB, Bezbaruah R, Ahmed N. Therapeutic drug repositioning with special emphasis on neurodegenerative diseases: Threats and issues. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2022 Oct 3;13:1007315.

- Ng YL, Salim CK, Chu JJ. Drug repurposing for COVID-19: Approaches, challenges and promising candidates. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2021 Dec 1;228:107930.

- Jurcau A, Andronie-Cioara FL, Nistor-Cseppento DC, Pascalau N, Rus M, Vasca E, Jurcau MC. The involvement of neuroinflammation in the onset and progression of Parkinson’s disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023 Sep 26;24(19):14582.

- Tolosa E, Garrido A, Scholz SW, Poewe W. Challenges in the diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. The Lancet Neurology. 2021 May 1;20(5):385-97.

- Shineman DW, Alam J, Anderson M, Black SE, Carman AJ, Cummings JL, Dacks PA, Dudley JT, Frail DE, Green A, Lane RF. Overcoming obstacles to repurposing for neurodegenerative disease. Annals of clinical and translational neurology. 2014 Jul;1(7):512-8.

- Dekker MC, Coulibaly T, Bardien S, Ross OA, Carr J, Komolafe M. Parkinson's disease research on the African continent: obstacles and opportunities. Frontiers in neurology. 2020 Jun 19;11:531501.

Vani Chatter*

Vani Chatter*

10.5281/zenodo.13850856

10.5281/zenodo.13850856