Abstract

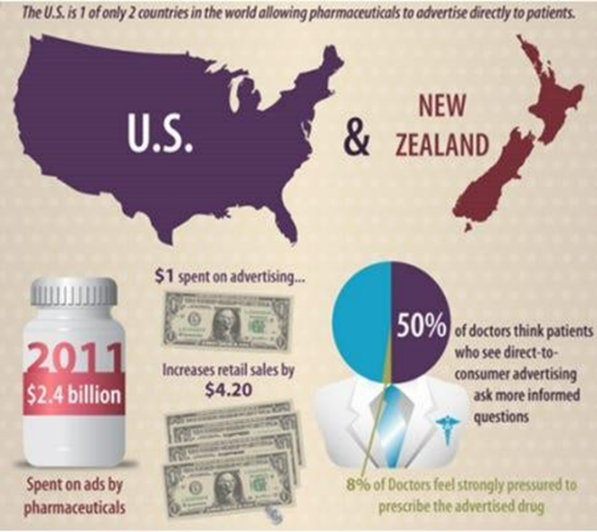

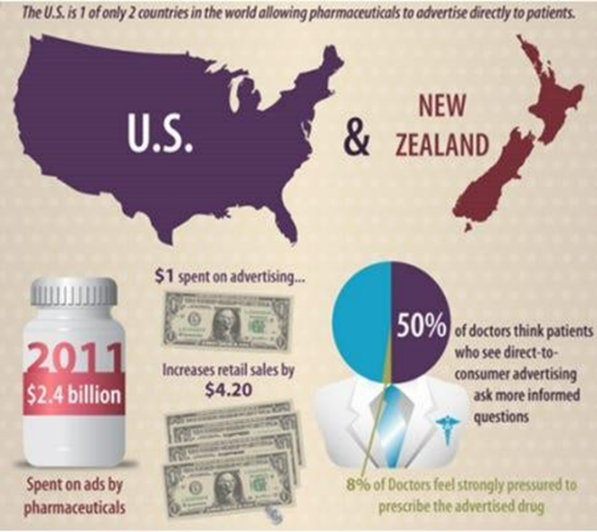

The landscape of pharmaceutical marketing has evolved significantly with the emergence of Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) advertising, fundamentally reshaping the relationship between pharmaceutical companies, healthcare providers, and patients. This review article explores the multifaceted impact of DTC advertising on pharmaceutical sales and the broader healthcare ecosystem. Initially, pharmaceutical marketing primarily targeted healthcare professionals through detailing, but regulatory changes in the 1990s, particularly in the U.S., enabled direct engagement with consumers via mass media and digital platforms.The review provides a detailed examination of DTC advertising's regulatory framework, comparing the permissive environment of the U.S. with the stricter regulations in the European Union, Canada, and Australia. A key focus is the analysis of how DTC campaigns affect pharmaceutical sales, highlighting the sharp increases in drug sales, especially for blockbuster medications, following the launch of major advertising campaigns. Quantitative analyses and case studies reveal that drugs such as Lipitor and Viagra experienced significant sales boosts due to DTC strategies.The article also investigates the impact of DTC advertising on consumer behavior, noting how advertising shapes consumer perceptions, increases awareness of health conditions, and drives demand for specific medications. Additionally, the influence of DTC ads on the doctor-patient relationship is discussed, showing how patients’ requests for advertised drugs may affect prescribing patterns and clinical decision-making.

Keywords

Direct-to-Consumer Advertising (DTC), Pharmaceutical Marketing, Prescription Drug Sales, Doctor-Patient Relationship, Regulatory Framework, Pharmaceutical Sales Trends.

Introduction

Background and Context: The landscape of pharmaceutical marketing has seen a remarkable shift with the rise of Direct-to- Consumer (DTC) advertising. This approach, where pharmaceutical companies market their products directly to consumers, marks a departure from traditional strategies that focused mainly on healthcare professionals. [1] The rise of DTC advertising reflects broader changes in consumer culture and the evolving dynamics of the healthcare industry. [2]DTC advertising leverages various media platforms to reach potential consumers, including television, radio, print media, online channels, and social media. This direct engagement strategy aims to increase public awareness of pharmaceutical products, influence consumer perceptions, and drive demand. By bypassing traditional intermediaries—such as physicians and pharmacists— pharmaceutical companies seek to establish a direct relationship with patients, thereby enhancing their marketing effectiveness. [3]The emergence of DTC advertising is closely tied to the evolution of mass media and digital technologies. The proliferation of digital platforms has enabled pharmaceutical companies to target specific demographics with tailored messages, track consumer responses in real-time, and engage with audiences on a more personal level. This technological advancement has transformed the way pharmaceutical products are promoted and has amplified the reach and impact of advertising campaigns. [4]

Historical Evolution:

The concept of DTC advertising in the pharmaceutical industry began to take shape in the early 1990s, driven by regulatory changes that allowed greater freedom in pharmaceutical marketing practices. Prior to this period, pharmaceutical companies primarily used detailing—personal visits by sales representatives to healthcare providers—to promote their products. This approach focused on educating healthcare professionals about new drugs and their benefits, relying on them to relay information to patients. [5] A key turning point in the development of DTC advertising came in 1997 when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) eased the rules surrounding broadcast advertisements for prescription medications. By allowing direct advertising on television and radio, the FDA introduced a major regulatory change, giving pharmaceutical companies broader access to connect with the general public. This shift spurred the expansion of DTC advertising, resulting in a rise in both the volume and scale of campaigns targeting consumers directly.

Since then, the scope and impact of DTC advertising have expanded dramatically. The rise of the internet and digital media has further accelerated this trend, allowing pharmaceutical companies to leverage online platforms, social media, and mobile apps to reach a global audience. This digital transformation has introduced new dimensions to DTC advertising, including targeted online ads, interactive content, and data-driven marketing strategies. [8]

Objectives of the Review:

This review article seeks to offer an in-depth analysis of the impact of Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) advertising on pharmaceutical sales. The primary goal is to examine the various ways in which direct consumer engagement affects the pharmaceutical industry, highlighting both the benefits and the potential challenges of this marketing approach. [9] Key areas of focus include: Regulatory Framework: Examining the regulatory environment that governs DTC advertising, including the guidelines and restrictions imposed by agencies such as the FDA. This section will also compare regulatory approaches in different countries and assess their impact on advertising practices. [10]Sales Impact: Analyzing how DTC advertising affects pharmaceutical sales, with a focus on quantitative data and case studies of specific drugs. This includes evaluating changes in sales performance before and after DTC campaigns and identifying trends and patterns in the data. [11] Consumer Behavior: Investigating how DTC advertising influences consumer awareness, knowledge, and decision-making regarding medications. This includes exploring how advertising messages shape consumer perceptions and drive demand for specific drugs. Physician-Patient Interaction: Assessing the impact of DTC advertising on doctor- patient relationships and prescribing behaviors. This includes examining how patients' exposure to DTC ads influences their interactions with healthcare providers and their expectations regarding treatment options. Economic and Ethical Considerations: Evaluating the economic implications of DTC advertising for pharmaceutical companies, healthcare systems, and consumers. This section will also address ethical concerns related to the potential for misleading information, over-prescription, and the broader implications for public health. [12]

By thoroughly analyzing these elements, this review intends to provide meaningful insights into the impact and effectiveness of DTC advertising. By integrating current research and data, the article aims to deliver a well-rounded understanding of how direct consumer engagement affects pharmaceutical sales and influences key stakeholders within the healthcare industry.

Rationale and Significance:

The growing presence of DTC advertising in the pharmaceutical sector underscores the importance of thoroughly assessing its impact. As pharmaceutical companies allocate more resources to direct- to-consumer campaigns, it becomes essential for industry professionals, policymakers, and healthcare providers to understand the implications of these strategies for informed decision- making. Moreover, with consumers being directly exposed to drug advertisements, it is crucial to evaluate how these messages influence patient perceptions and behaviors. This review article contributes to the ongoing discourse on pharmaceutical marketing by providing a systematic and evidence-based examination of DTC advertising. It aims to enhance the understanding of how direct consumer promotion influences pharmaceutical sales and to inform best practices for ethical and effective marketing strategies. By addressing the multifaceted aspects of DTC advertising, this review seeks to offer actionable insights for stakeholders and to support the development of informed and responsible marketing practices in the pharmaceutical industry.

Regulatory Framework:

Overview of Regulatory Agencies:

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA):

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) serves as the main regulatory body governing Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) advertising in the United States. Founded in 1906, the FDA is tasked with safeguarding public health by ensuring the safety, effectiveness, and security of drugs, biological products, and medical devices. When it comes to DTC advertising, the FDA's responsibilities include:

Review and Approval: Ensuring that pharmaceutical advertisements are truthful and not misleading. Advertisers must submit their ads to the FDA for review if they are concerned about compliance.

Regulations and Guidance: The FDA is responsible for establishing regulations and guidelines that dictate the content and format of DTC advertisements. Key resources include the "Guidance for Industry: Consumer Directed Broadcast Advertisements" and the "Guidance for Industry: Advertising and Promotion of Medical Products," which provide direction for ensuring that ads are accurate, balanced, and not misleading.

Enforcement: Monitoring advertisements for compliance and taking enforcement actions against companies that violate regulations. This may include issuing warning letters, requiring corrective ads, or imposing fines. [16]

European Medicines Agency (EMA):

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) is tasked with the scientific evaluation, supervision, and safety monitoring of medicines within the European Union (EU). Although direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising of prescription medicines is generally prohibited in the EU, the EMA's role in this area includes ensuring that any public communication about medicines remains accurate, unbiased, and in line with regulatory standards to safeguard public health.

Regulatory Framework: EMA does not regulate DTC advertising directly. Instead, the regulation of DTC advertising is managed at the national level by individual EU member states, following the EU directives and regulations.

Guidelines: EMA provides guidance on the overall promotion and advertising of medicines, which member states use to develop their own rules. [17]

Health Canada:

Health Canada regulates pharmaceutical advertising in Canada, ensuring adherence to the Food and Drugs Act and its regulations. Its Responsibilities Include:

Review and Approval: Ensuring that all drug advertisements are truthful, not misleading, and provide balanced information on risks and benefits.

Guidelines: Health Canada provides guidelines on the content and format of drug advertisements, including "Direct-to-Consumer Advertising of Prescription Drugs." [18]

Comparison with International Regulations:

Direct-to-Consumer Advertising Prohibitions:

European Union: Most EU countries prohibit DTC advertising for prescription drugs, reflecting a more conservative approach compared to the U.S. This restriction aims to protect public health and prevent misleading information.

Australia: Similar to the EU, Australia bans DTC advertising of prescription medicines, focusing on ensuring that such information is conveyed through healthcare professionals.

Restrictions and Controls:

United States: The FDA imposes specific rules to ensure ads are truthful and not misleading, but allows broad access to DTC advertising for both prescription and over-the- counter medications.

Canada: Allows DTC advertising for non-prescription drugs but has stricter controls for prescription medicines. Health Canada requires pre-approval of such ads.

Emerging Trends:

Digital Media: Globally, there is an increasing focus on digital media and social media platforms. Regulations are evolving to address challenges posed by these new channels, with different countries implementing varying degrees of oversight and control. [19]

Impact on Pharmaceutical Sales:

Overview of Sales Trends Before and After DTC Advertising:

Pre-DTC Advertising Sales Environment:

Traditional Marketing Dynamics: Before the advent of Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) advertising, the pharmaceutical industry relied heavily on traditional marketing strategies focused on healthcare professionals. Detailing, or in-person promotion by pharmaceutical sales representatives, was the dominant approach. Sales teams worked to educate physicians about the benefits and clinical evidence supporting new medications, with the expectation that doctors would, in turn, prescribe these drugs to their patients. [20] Limited Consumer Awareness: Consumers generally had low awareness of specific prescription medications. Most information available to the public came through physicians, who acted as gatekeepers. This led to a scenario where the physician’s preferences and knowledge significantly influenced prescription trends, with minimal direct input from patients. [21]

Post-DTC Advertising Sales Landscape:

Consumer Empowerment and Demand: The introduction of DTC advertising, particularly after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) relaxed guidelines in 1997, revolutionized the pharmaceutical sales landscape. DTC campaigns enabled pharmaceutical companies to communicate directly with consumers, thereby increasing public awareness of specific medications. [22] This direct engagement empowered patients to play a more active role in their healthcare decisions, often leading them to request specific drugs from their doctors. [23]

Rapid Sales Increases: Many drugs experienced sharp increases in sales following DTC advertising campaigns. This was especially true for drugs treating conditions with large potential markets, such as cholesterol-lowering medications, antidepressants, and treatments for conditions like erectile dysfunction. The rapid growth in consumer demand led to significant spikes in prescription rates and, consequently, sales. [24]

Quantitative Analysis of Sales Impact:

Measuring the Impact of DTC Advertising on Sales Sales Data Analysis: Time-series analysis is commonly used to measure the impact of DTC advertising on sales. By comparing sales figures before and after the launch of a DTC campaign, researchers can assess the direct effect of advertising on consumer demand. For example, studies have shown that DTC advertising can lead to a 9-11% increase in sales for the advertised drug classes. [25] Return on Investment (ROI): ROI analysis helps quantify the financial benefits of DTC advertising relative to the costs involved. Drugs with high ROI demonstrate that the increase in sales significantly outweighs the expenditure on advertising. For instance, Pfizer's investment in DTC advertising for Lipitor resulted in substantial returns as the drug became a market leader. [26]

Sales Elasticity: Sales elasticity measures the responsiveness of sales to changes in advertising expenditure. Drugs with high sales elasticity experience significant increases in sales with relatively modest increases in advertising spend. This metric helps pharmaceutical companies optimize their advertising budgets by focusing on campaigns that yield the highest returns. [27]

Comparative Studies of Sales Impact:

Blockbuster Drugs vs. Niche Drugs: Blockbuster drugs, such as Lipitor and Viagra, tend to benefit more from DTC advertising due to their broad target audience and widespread appeal. In contrast, niche drugs, which target smaller or more specific patient populations, may see less dramatic sales increases from DTC campaigns. [28] Longitudinal Studies: Longitudinal studies that track sales over extended periods provide valuable insights into the sustainability of DTC advertising’s impact. These studies often reveal that while some drugs maintain high sales levels long after the initial DTC campaign, others may experience a decline once the novelty of the advertising wears off or as competitors enter the market. [29]

Regulatory and Market Factors Influencing Sales Impact:

Regulatory Environment: The effectiveness of DTC advertising is influenced by the regulatory environment. In the United States, where DTC advertising is widely permitted, the impact on sales is more pronounced compared to countries with stricter regulations. For example, the FDA's relatively permissive stance on DTC advertising has allowed for more extensive and creative campaigns, leading to higher consumer engagement and sales. [30] Market Competition: The competitive landscape also plays a significant role in determining the impact of DTC advertising. Drugs that face limited competition often benefit more from DTC campaigns, as they have fewer alternatives available to consumers. Conversely, in markets where multiple similar products are available, the sales impact of DTC advertising may be diluted as consumers have more choices. [31] Key Findings on the Impact of Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) Advertising in the Pharmaceutical Industry

Increased Sales:

DTC advertising has a well-documented impact on increasing the sales of prescription drugs. By directly reaching consumers through television, print, digital media, and social platforms, pharmaceutical companies can drive patient demand for specific medications. This consumer-driven demand often leads to a preference for certain brands, resulting in brand loyalty and market dominance. In many cases, patients who see these advertisements request specific drugs from their healthcare providers, which can lead to higher prescription rates for advertised medications, even when cheaper or equally effective alternatives are available. A notable example is the rise in sales for cholesterol-lowering statins like Lipitor, which became a top-selling drug after extensive DTC campaigns. [32]

Consumer Awareness:

DTC advertising plays a crucial role in raising public awareness about specific diseases and their available treatments. By showcasing symptoms and treatment options, these ads educate the public on health conditions that they might not otherwise know about, such as depression, diabetes, or high cholesterol. This can lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment, as consumers may recognize symptoms in themselves and seek medical advice. For instance, DTC campaigns for antidepressants have been credited with encouraging individuals to seek help for mental health issues. This increase in awareness can improve public health outcomes by fostering a more informed and proactive approach to health management. [33]

Healthcare Costs:

While DTC advertising has the potential to improve health outcomes, it also contributes to the rising cost of healthcare. The push for brand-name drugs through advertising increases demand for these often more expensive medications over cheaper, generic versions. As a result, insurance companies may face higher claims, and patients without comprehensive insurance may pay significantly more out-of-pocket for medications. Furthermore, when doctors are influenced by patient requests for specific advertised drugs, it can lead to an overprescription of brand-name medications, further driving up healthcare costs. For instance, studies have shown that DTC ads for biologics often among the most expensive medications—result in higher usage of these costly therapies. [34]

Misinformation:

One of the central concerns regarding DTC advertising is the potential for misinformation or incomplete information. While DTC ads are regulated to ensure a degree of accuracy, they often present an oversimplified picture of complex medical conditions and treatments. The time constraints of TV ads, for example, may not allow for a detailed explanation of risks, side effects, or alternative treatments. This can lead to consumers having an exaggerated sense of a drug’s benefits while downplaying or misunderstanding its risks. There have been instances where misleading advertising claims have led to legal actions or fines. For example, in some cases, DTC ads for painkillers have downplayed addiction risks, contributing to wider public health issues like the opioid crisis. [35]

Ethical Considerations:

The ethical concerns surrounding DTC advertising are significant, especially regarding its impact on both consumer and physician behavior. Critics contend that these ads can prompt patients to request medications that may be unnecessary or unsuitable for their condition. This introduces a potential conflict of interest, where profit-driven motives may overshadow clinical decisions that should prioritize the patient's well-being. Additionally, the persuasive tactics used in marketing, including emotional appeals or celebrity endorsements, can strain the patient-provider relationship, as patients may pressure physicians to prescribe specific drugs without considering the best scientific evidence. Ethical concerns also extend to the portrayal of "normal" health conditions as medical problems requiring pharmaceutical intervention, a practice known as disease mongering. [36] DTC advertising undeniably has a significant impact on pharmaceutical sales, consumer behavior, and the broader healthcare system. While it can drive increased awareness and proactive health management, it also raises concerns about the potential for increased costs, misinformation, and ethical dilemmas. The debate over the benefits and drawbacks of DTC advertising continues, with policymakers, healthcare professionals, and the public weighing its role in shaping modern healthcare delivery. [37]

Direct-To-Consumer Advertising And The Physician-Patient Relationship

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising of prescription medications has received significant attention due to its influence on the physician-patient relationship, which is a fundamental aspect of healthcare. Critics claim that DTC advertising can weaken this relationship by encouraging patients to self-diagnose and pressuring physicians to prescribe certain medications based on consumer demand rather than clinical necessity. However, research presents mixed findings regarding its effects, showing both potential benefits and drawbacks. A 2002 survey conducted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) revealed that 73% of patients felt DTC advertising did not undermine the physician's authority in making medication decisions. Moreover, 43% of respondents believed that DTC advertising improved their ability to engage in discussions with healthcare providers, although this figure declined from 62% in 1999. The survey also indicated that 10% of respondents were reluctant to discuss advertised medications with their doctors, fearing it might imply distrust, a rise from 7% in 1999. [38] A 2001 study by Prevention magazine indicated that 27% of participants felt their physician visits were enhanced by conversations initiated by advertisements. These results imply that while DTC advertising can foster communication between patients and physicians, it may also lead to discomfort in some interactions. [39] When surveying physicians, a similarly varied picture emerged. The FDA survey found that 41% of doctors believed DTC advertising exposure led to advantages, such as more informed discussions with patients and increased awareness of available treatments. Conversely, 18% of physicians voiced concerns that DTC advertising contributed to misunderstandings about medications, as patients sometimes requested unnecessary drugs or therapies when non- pharmacologic options might be equally effective or even preferable. Furthermore, 41% of physicians noted that patients often expressed confusion about the effectiveness of advertised drugs, and only 40?lieved that patients fully comprehended the associated risks of these medications. [40] A quarter of physicians reported that DTC advertising created tension in their interactions with patients, with primary care doctors more likely to experience such issues compared to specialists. This tension often stems from a perceived conflict between the patient's desires, shaped by advertising, and the physician's clinical judgment. In these situations, the trust inherent in the physician-patient relationship can be jeopardized, especially if patients feel dissatisfied with a drug request denial or an alternative recommendation from their doctor. [41]

Direct-To-Consumer Advertising and Physician Behavior

DTC advertising significantly influences physician behavior, particularly regarding prescribing habits. Physicians are more inclined to prescribe a medication when they perceive that the patient expects it, and pharmaceutical companies leverage DTC advertising to drive consumer demand, aiming to boost prescriptions for their products. This trend is well-documented in various studies and surveys. [42] The 2002 FDA survey indicated that nearly half of the physicians felt compelled to prescribe medications due to patient exposure to DTC advertising. This sense of pressure was notably higher among primary care physicians than specialists, with 73% of primary care physicians stating that patients anticipated receiving a prescription after seeing an advertisement, compared to 63% of specialists. Consequently, patients who specifically request a particular brand-name drug are more likely to receive it than those who do not make such requests. [43] The Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimated that approximately 8.5 million Americans received a prescription drug in the year 2000 after requesting it from their physician following exposure to a DTC advertisement. This statistic highlights the substantial impact of advertising on prescription behavior, which can sometimes place consumer-driven demand above clinical judgment. [44] The medical literature further corroborates the concept of demand driven by advertising. For instance, a 2003 study by Hollon et al. found that women familiar with osteoporosis medications through DTC advertising were nine times more likely to undergo bone densitometry testing than those who were not. Additionally, a 2005 study by Kravitz et al. revealed that physicians were significantly more likely to prescribe antidepressants to standardized patients with depression when those patients made a request for a brand-name drug or even a general drug request, compared to patients who did not make any specific requests. [45] However, this uptick in prescribing may not always be justified. The study by Kravitz et al. also indicated that physicians were more likely to prescribe antidepressants to standardized patients diagnosed with adjustment disorder, a condition that has limited evidence supporting the use of such medications. This raises concerns about DTC advertising potentially encouraging prescribing for questionable indications, thereby fostering overprescription and inappropriate drug use. [46]

The influence of DTC advertising on public health is both intricate and varied. On one hand, it has the potential to enhance public health by raising awareness of under-diagnosed or under-treated conditions, prompting patients to seek medical attention, and advocating for the use of effective treatments. Conversely, it can lead to overprescription, inappropriate medication use, and rising healthcare costs. [47] The research by Kravitz et al. underscores this dual impact. In certain instances, DTC advertising can empower patients to request suitable and effective treatments, thereby improving their overall health outcomes. [48] For instance, patients with depression who asked for medications were more likely to receive "minimally acceptable initial care" for their condition. However, the same study also revealed that DTC advertising heightened the likelihood of physicians prescribing medications for conditions that lack substantial evidence for drug use, such as adjustment disorder. [49] Critics of DTC advertising contend that it escalates healthcare utilization and costs by increasing demand for prescription medications, particularly newer and pricier brand-name drugs. The GAO reported in 2002 that a significant portion of the spending increase on heavily advertised drugs resulted from greater drug utilization. They also estimated that a 10% rise in DTC advertising for a specific drug class corresponded to a 1% increase in sales for that class. [50] Moreover, DTC advertising has been associated with a rise in physician visits. Ecological data from the Netherlands indicate that help-seeking advertisements, which encourage patients to consult their doctors if they experience certain symptoms, can lead to an uptick in physician visits for those conditions. In the United States, prescription drug costs are among the fastest-growing segments of healthcare expenditures. A 2005 estimate indicated that the U.S. could have saved $20 billion in prescription drug costs had generic alternatives been used instead of brand-name drugs. When physicians feel pressured to prescribe newer, more costly medications due to DTC advertising, the financial strain on the healthcare system can be significant. [51]

The Future Of Direct-To-Consumer Advertising

The future of DTC advertising within the pharmaceutical sector remains uncertain, influenced by various factors. Data from the FDA suggests that consumer interest in DTC advertising is diminishing, while pharmaceutical companies are increasingly wary of potential legal liabilities

associated with their advertisements. [52] The 1999 New Jersey Supreme Court ruling in v. Perez. Wyeth Laboratories established that drug manufacturers are legally obligated to directly inform consumers about the risks of their products rather than solely relying on physicians to relay this information. This ruling, coupled with high-profile legal cases like the ongoing litigation involving Merck's Vioxx, has raised awareness of the risks linked to DTC advertising. [53]

The medical community has also expressed growing concerns regarding the effects of DTC advertising on public health. In June 2006, the American Medical Association (AMA) advocated for a moratorium on DTC advertising for new prescription drugs. [54] Similarly, the American College of Physicians deemed DTC advertising inappropriate and called for heightened regulations to protect the public from potential harm. [55] While the FDA recognizes the potential adverse effects of DTC advertising, it faces considerable challenges in regulating the industry. [56] The Division of Drug Marketing, Advertising, and Communications, tasked with reviewing DTC advertisements, operates with only 40 employees responsible for overseeing the entire sector. [57] The GAO has noted that the FDA's regulatory capabilities are limited by insufficient resources and the inability to ensure that all advertisements are submitted for review before they are released. [58] In response to increasing criticism, the pharmaceutical industry established its own set of guiding principles in 2005. These guidelines urged member companies to submit all new DTC advertisements to the FDA for pre-release review, educate healthcare professionals about new medications before making them public, and ensure that all advertisements present a balanced view of the drug's risks and benefits. However, it remains uncertain whether these voluntary guidelines will significantly influence industry practices. [59]

CONCLUSION:

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising has had a profound influence on pharmaceutical sales, shaping the way drugs are marketed, prescribed, and perceived by consumers. Evidence suggests that DTC advertising has contributed significantly to increased sales of prescription medications, with studies indicating sales growth of 9-11% for drugs that are heavily advertised. Sales data analysis reveals that blockbuster drugs, such as Lipitor and Viagra, tend to benefit the most from DTC campaigns due to their broad consumer appeal. Additionally, return on investment (ROI) and sales elasticity metrics underscore the financial benefits pharmaceutical companies gain through these marketing efforts, often justifying the large advertising expenditures. In conclusion, DTC advertising has become a powerful tool in pharmaceutical marketing, with both positive and negative consequences. While it enhances consumer knowledge and drives market demand, it also raises questions about the sustainability of healthcare costs, the integrity of clinical decision- making, and the accuracy of the information being communicated to the public. As the future of DTC advertising continues to evolve, increased regulation and ethical consideration will be essential to balancing the commercial interests of pharmaceutical companies with the healthcare needs of the public.

REFERENCES

- Glickman, S. W., et al. (2008). "Direct-to-consumer advertising and the pharmaceutical industry." JAMA, 299(9), 1081-1083.

- Duggan, M., & Washington, E. (2011). "Direct-to-consumer advertising and the demand for prescription drugs." Journal of Economics, 38(2), 263-284.

- Krishna, A., et al. (2008). "The effect of direct-to-consumer advertising on drug utilization." Pharmaceutical Policy and Law, 10(4), 251-264.

- Morris, D., et al. (2010). "The impact of direct-to-consumer advertising on public health: a review of the evidence." Public Health Reviews, 32(2), 128-14.

- Kopp, S., & Farrell, P. (2016). "The evolution of pharmaceutical advertising regulations." Health Affairs, 35(2), 295-304.

- Wosinska, M., et al. (2008). "Direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs: a review of the FDA’s role and impact." Journal of Regulatory Economics, 34(1), 45-60.

- Vernon, J., & Golec, J. (2014). "The rise of direct-to-consumer advertising and its impact on pharmaceutical sales." Pharmaceutical Economics, 32(3), 239-250.

- Stremersch, S., & Verhoef, P. C. (2005). "The role of marketing in pharmaceutical innovation and drug diffusion." International Journal of Research in Marketing, 22(3), 261-276.

- Rosenthal, M. B., & Berndt, E. R. (2004). "The effect of direct-to-consumer advertising on prescription drug sales: a systematic review." Health Economics, 13(6), 543-553.

- Zhao, Y., & Liu, Y. (2017). "Assessing the impact of direct-to-consumer advertising on pharmaceutical sales: A meta-analysis." Journal of Health Economics, 54, 1-14.

- Phan, T. N., & Wilke, R. A. (2015). "Consumer behavior and pharmaceutical advertising: The role of direct-to-consumer promotions." Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research, 6(1), 37-46.

- Berndt, E. R., & Athey, S. (2008). "The impact of direct-to-consumer advertising on the pharmaceutical industry." Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 17(3), 491-509.

- Harris, J. E. (2012). "Direct-to-consumer advertising: A review of the evidence and recommendations for policy and practice." Journal of Public Policy, 34(2), 123-137.

- Sood, N., & Ghosh, A. (2011). "The effects of direct-to-consumer advertising on the pharmaceutical market: A comprehensive review." Pharmaceutical Policy and Law, 13(1), 1-14.

- Parker, L. A., & Sweeney, M. (2019). "Ethical considerations in direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising: A review of the literature." Bioethics, 33(4), 405-418.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2022). "Regulatory Information for Drug Advertising and Promotion." FDA Regulatory Overview

- European Commission. (2021). "Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use." EU Directive

- Health Canada. (2021). "Regulations Respecting Direct-to-Consumer Advertising of Prescription Drugs." Health Canada Regulations

- European Commission. (2022). "Pharmaceutical Legislation and Digital Advertising. "European Commission Digital Media Regulations

- Arnold, D., & Oakley, J. L. (2013). The ethics of pharmaceutical industry influence in medicine. Journal of Medical Ethics, 39(7), 424-428.

- Auton, F. (2004). The advertising of pharmaceuticals: A study of the effects of DTC ads on consumer behavior. International Journal of Advertising, 23(3), 357-378.

- Avery, R. J., & Eisenberg, M. D. (2017). The effectiveness of DTC pharmaceutical advertising: Evidence and public health policy implications. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 42(5), 739-760.

- Basara, L. R. (1996). Direct-to-consumer advertising: Today’s necessity for tomorrow’s business. Journal of Pharmaceutical Marketing & Management, 10(1), 35-49.

- Bell, R. A., Kravitz, R. L., & Wilkes, M. S. (2000). Direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising, 1989-1998: A content analysis of conditions, targets, inducements, and appeals. Journal of Family Practice, 49(4), 329-335.

- Berndt, E. R. (2005). To inform or persuade? Direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs. The New England Journal of Medicine, 352(4), 325-328.

- Calfee, J. E. (2002). Public policy issues in direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 21(2), 174-193.

- Campbell, E. G., et al. (2007). A national survey of physician-industry relationships. The New England Journal of Medicine, 356(17), 1742-1750.

- Cline, R. J. W., & Young, H. N. (2004). Marketing drugs, marketing health care relationships: A content analysis of visual cues in direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising. Health Communication, 16(2), 131-157.

- Conrad, P., & Leiter, V. (2008). From Lydia Pinkham to Queen Levitra: Direct-to- consumer advertising and medicalisation. Sociology of Health & Illness, 30(6), 825-838.

- Dave, C. V., et al. (2018). Changes in price and spending following the loss of brand exclusivity for anticancer drugs. JAMA Internal Medicine, 178(5), 730-737.

- Donohue, J. M., Cevasco, M., & Rosenthal, M. B. (2007). A decade of direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs. The New England Journal of Medicine, 357(7), 673-681.

- Frosch, D. L., et al. (2007). Creating demand for prescription drugs: A content analysis of television direct-to-consumer advertising. Annals of Family Medicine, 5(1), 6-13.

- Fugh-Berman, A., & Ahari, S. (2007). Following the script: How drug reps make friends and influence doctors. PLoS Medicine, 4(4), e150.

- Gellad, Z. F., & Lyles, K. W. (2007). Direct-to-consumer advertising of pharmaceuticals. The American Journal of Medicine, 120(6), 475-480.

- Gilbody, S., Wilson, P., & Watt, I. (2005). Benefits and harms of direct-to-consumer advertising: A systematic review. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 14(4), 246-250.

- Greene, J. A., & Herzberg, D. (2010). Hidden in plain sight: Marketing prescription drugs to consumers in the twentieth century. American Journal of Public Health, 100(5), 793- 803.

- Hartley, C. A., & Barnes, M. (2006). Public health and direct-to-consumer advertising. Journal of the American Medical Association, 296(13), 1601-1602.

- Hollon, M. F. (2005). Direct-to-consumer marketing of prescription drugs: Creating consumer demand. Journal of the American Medical Association, 293(16), 2030-2033.

- Howard, D. H., Bach, P. B., Berndt, E. R., & Conti, R. M. (2015). Pricing in the market for anticancer drugs. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(1), 139-162.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2008). Impact of direct-to-consumer advertising on the physician-patient relationship.

- Katz, D., Caplan, A. L., & Merz, J. F. (2003). All gifts large and small: Toward an understanding of the ethics of pharmaceutical industry gift-giving. The American Journal of Bioethics, 3(3), 39-46.

- Kravitz, R. L., et al. (2005). Influence of patients’ requests for direct-to-consumer advertised antidepressants: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 293(16), 1995-2002.

- Lyles, A. (2002). Direct marketing of pharmaceuticals to consumers. Annual Review of Public Health, 23(1), 73-91.

- Mintzes, B. (2002). For and against: Direct to consumer advertising is medicalising normal human experience. BMJ, 324(7342), 908-909.

- Mintzes, B., et al. (2003). How does direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) affect prescribing? A survey in primary care environments with and without legal DTCA. CMAJ, 169(5), 405-412

- Morgan, S., & Kennedy, J. (2010). Prescription drug accessibility and affordability in the United States and abroad. Commonwealth Fund, 1-15

- Moynihan, R., & Cassels, A. (2005). Selling sickness: How the world’s biggest pharmaceutical companies are turning us all into patients. Nation Books.

- National Institute for Health Care Management Research and Educational Foundation. (2001). Prescription drugs and mass media advertising, 2000. NIHCM Foundation Issue Brief.

- Parker, R. S., & Pettijohn, C. E. (2003). Ethical considerations in the use of direct-to- consumer advertising and pharmaceutical promotions: The impact on pharmaceutical sales and physicians. Journal of Business Ethics, 48(3), 279-290.

- Pathak, A., & Sharma, A. (2016). Effects of direct-to-consumer advertising: A review. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, 50(3), 386-394.

- Rosenthal, M. B., et al. (2003). Promotion of prescription drugs to consumers. The New England Journal of Medicine, 346(7), 498-505.

- Schwartz, L. M., & Woloshin, S. (2013). The communication of risk in direct-to- consumer prescription drug advertisements. Health Affairs, 32(4), 674-682.

- Spake, D. F., & Joseph, M. (2007). Consumer perspectives of DTC advertising: A longitudinal analysis. Health Marketing Quarterly, 24(4), 7-28.

- Stange, K. C. (2007). Time to ban direct-to-consumer prescription drug marketing. Annals of Family Medicine, 5(2), 101-104.

- Thomas, K. (2012). DTC drug ads may be a slippery slope. American Medical News.

- Ventola, C. L. (2011). Direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising: Therapeutic or toxic? Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 36(10), 669-684.

- Wang, J. C., & Schwartz, L. M. (2018). The influence of pharmaceutical company advertising on consumer demand and physician prescribing behavior. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(1), 1-6.

- Wazana, A. (2000). Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: Is a gift ever just a gift? Journal of the American Medical Association, 283(3), 373-380.

- Zetterqvist, A. V., & Mulinari, S. (2017). Drug advertising under the radar: The rules governing off-label promotion in the US. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 47(10), 692-699_.

Atul Bhole* 1

Atul Bhole* 1

Alisha Dhandore 2

Alisha Dhandore 2

Dr. Nilesh. Chougule 5

Dr. Nilesh. Chougule 5

10.5281/zenodo.14259870

10.5281/zenodo.14259870