Anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder/agoraphobia, social anxiety disorder, and others) are the most prevalent psychiatric disorders, and are associated with a high burden of illness. Anxiety disorders are often underrecognized and undertreated in primary care. Treatment is indicated when a patient shows marked distress or suffers from complications resulting from the disorder. The treatment recommendations given in this article are based on guidelines, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews of randomized controlled studies. Anxiety disorders should be treated with psychological therapy, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of both. Cognitive behavioral therapy can be regarded as the psychotherapy with the highest level of evidence. First-line drugs are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin- norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Benzodiazepines are not recommended for routine use. Other treatment options include pregabalin, tricyclic antidepressants, buspirone, moclobemide, and others. After remission, medications should be continued for 6 to 12 months. When developing a treatment plan, efficacy, adverse effects, interactions, costs, and the preference of the patient should be considered.

Drug treatment, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, psychotherapy, social anxiety disorder, treatment.

Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent psychiatric disorders and are associated with a high burden of illness. With a 12-month prevalence of 10.3%, specific (isolated) phobias are the most common anxiety disorders, although persons suffering from isolated phobias rarely seek treatment. Panic disorder with or without agoraphobia (PDA) is the next most common type with a prevalence of 6.0%, followed by social anxiety disorder (SAD, also called social phobia; 2.7%) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD; 2.2%). Evidence is lacking on whether these disorders have become more frequent in recent decades. Women are 1.5 to two times more likely than men to receive a diagnosis of anxiety disorder. The age of onset for anxiety disorders differs among the disorders. Separation anxiety disorder and specific phobia start during childhood, with a median age of onset of 7 years, followed by SAD (13 years), agoraphobia without panic attacks (20 years), and panic disorder (24 years). GAD may start even later in life. Anxiety disorders tend to run a chronic course, with symptoms fluctuating in severity between periods of relapse and remission in GAD and PDA and a more chronic course in SAD. After the age of 50, a marked decrease in the prevalence of anxiety disorders has been observed in epidemiological studies. GAD is the only anxiety disorder that is still common in people aged 50 years or more. The current conceptualization of the etiology of anxiety disorders includes an interaction of psychosocial factors, eg, childhood adversity, stress, or trauma, and a genetic vulnerability, which manifests in neurobiological and neuropsychological dysfunctions. The evidence for potential biomarkers for anxiety disorders in the fields of neuroimaging, genetics, neurochemistry, neurophysiology, and neurocognition has been summarized in two recent consensus papers. Despite comprehensive, high-quality neurobiological research in the field of anxiety disorders, these reviews indicate that specific biomarkers for anxiety disorders have yet to be identified. Thus, it is difficult to give recommendations for specific biomarkers (eg, genetic polymorphisms) that could help identify persons at risk for an anxiety disorder. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were formerly included in the anxiety disorders, but have now been placed in other chapters in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Therefore, OCD and PTSD are not discussed in this review.

Defination

Anxiety is an emotion characterized by feelings of tension, worried thoughts, and physical changes like increased blood pressure. People with anxiety disorders usually have recurring intrusive thoughts or concerns. They may avoid certain situations out of worry. They may also have physical symptoms such as sweating, trembling, dizziness, or a rapid heartbeat. Anxiety is not the same as fear, but they are often used interchangeably. Anxiety is considered a future-oriented, long-acting response broadly focused on a diffuse threat, whereas fear is an appropriate, present-oriented, and short-lived response to a clearly identifiable and specific threat.

CLASSIFICATION:

- Panic Disorder

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder

- Phobic Disorders

- Stress Disorders

- Obessive-Compulsive Disorder

Panic Disorder:

People with panic disorder have frequent and unexpected panic attacks. These attacks are characterized by a sudden wave of fear or discomfort or a sense of losing control even when there is no clear danger or trigger. Not everyone who experiences a panic attack will develop panic disorder.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder:

Generalized anxiety disorder is characterized by persistent, excessive, and unrealistic worry about everyday things. This worry could be multifocal such as finance, family, health, and the future. It is excessive, difficult to control, and is often accompanied by many non-specific psychological and physical symptoms.

Phobic Disorders:

A phobia is a type of anxiety disorder that causes an individual to experience extreme, irrational fear about a situation, living creature, place, or object. When a person has a phobia, they will often shape their lives to avoid what they consider to be dangerous. The imagined threat is greater than any actual threat posed by the cause of terror. Phobias are diagnosable mental disorders The person will experience intense distress when faced with the source of their phobia. This can prevent them from functioning normally and sometimes leads to attacks. In the United States, approximately 19 million people have phobias.

Stress Disorders: Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a disorder that develops in some people who have experienced a shocking, scary, or dangerous event. It is natural to feel afraid during and after a traumatic situation. Fear is a part of the body's “fight-or-flight” response, which helps us avoid or respond to potential danger.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a long-lasting disorder in which a person experiences uncontrollable and recurring thoughts (obsessions), engages in repetitive behaviors (compulsions), or both. People with OCD have time-consuming symptoms that can cause significant distress or interfere with daily life.

Substance-induced anxiety disorder is characterized by symptoms of intense anxiety or panic that are a direct result of misusing drugs, taking medications, being exposed to a toxic substance or withdrawal from drugs.

Other specified anxiety disorder and unspecified anxiety disorder are terms for anxiety or phobias that don't meet the exact criteria for any other anxiety disorders but are significant enough to be distressing and disruptive.

Selective mutism is a consistent failure of children to speak in certain situations, such as school, even when they can speak in other situations, such as at home with close family members. This can interfere with school, work and social functioning.

Separation anxiety disorder is a childhood disorder characterized by anxiety that's excessive for the child's developmental level and related to separation from parents or others who have parental roles.

Clinical Manifestations:

Common anxiety signs and symptoms include:

- Feeling nervous, restless or tense

- Having a sense of impending danger, panic or doom

- Having an increased heart rate

- Breathing rapidly (hyperventilation)

- Sweating

- Trembling

- Feeling weak or tired

- Trouble concentrating or thinking about anything other than the present worry

- Having trouble sleeping

- Experiencing gastrointestinal (GI) problems

- Having difficulty controlling worry

- Having the urge to avoid things that trigger anxiety

Principles Of Managing Anxiety Disorder:

Some of the management options for anxiety disorders include:

- learning about anxiety

- mindfulness

- relaxation techniques

- correct breathing techniques

- cognitive therapy

- behaviour therapy

- counselling

- dietary adjustments

- exercise

- learning to be assertive

- building self-esteem

- structured problem solving

- medication

- support groups

Learning about anxiety

The old adage ‘knowledge is power’ applies here – learning all about anxiety is central to recovery. For example, education includes examining the physiology of the ‘flight-or-fight’ response, which is the body’s way to deal with impending danger. For people with anxiety disorders, this response is inappropriately triggered by situations that are generally harmless. Education is an important way to promote control over symptoms.

Relaxation techniques

A person who feels anxious most of the time has trouble relaxing, but knowing how to release muscle tension can be a helpful strategy. Relaxation techniques include:

- progressive muscle relaxation

- abdominal breathing

- isometric relaxation exercises.

Cognitive therapy

Cognitive therapy focuses on changing patterns of thinking and beliefs that are associated with, and trigger, anxiety. For example, a person with a social phobia may make their anxiety worse by negative thoughts such as, ‘Everyone thinks I’m boring’. The basis of cognitive therapy is that beliefs trigger thoughts, which then trigger feelings and produce behaviours. For example, let’s say you believe (perhaps unconsciously) that you must be liked by everyone in order to feel worthwhile. If someone turns away from you in mid- conversation, you may think, ‘This person hates me’, which makes you feel anxious. Cognitive therapy strategies include rational ‘self-talk’, reality testing, attention training, cognitive challenging and cognitive restructuring. This includes monitoring your self-talk, challenging unhelpful fears and beliefs, and testing out the reality of negative thoughts.

Behaviour therapy

A major component of behaviour therapy is exposure. Exposure therapy involves deliberately confronting your fears in order to desensitise yourself. Exposure allows you to train yourself to redefine the danger or fear aspect of the situation or trigger.

The steps of exposure therapy may include:

- Rank your fears in order, from most to least threatening.

- Choose to work first on one of your least threatening fears.

- Think about the feared situation. Imagine yourself experiencing the situation. Analyse your fears -– what are you afraid of?

- Work out a plan that includes a number of small steps – for example, gradually decrease the distance between yourself and the feared situation or object, or gradually increase the amount of time spent in the feared situation.

- Resist the urge to leave. Use relaxation, breathing techniques and coping statements to help manage your anxiety.

- Afterwards, appreciate that nothing bad happened.

- Repeat the exposure as often as you can to build confidence that you can cope.

- When you are ready, tackle another feared situation in the same step-by-step manner.

Dietary adjustments

The mineral magnesium helps muscle tissue to relax, and a magnesium deficiency can contribute to anxiety, depression and insomnia. Inadequate intake of vitamin B and calcium can also exacerbate anxiety symptoms. Nicotine, caffeine and stimulant drugs (such as those that contain caffeine) trigger your adrenal glands to release adrenaline, which is one of the main stress chemicals. These are best avoided. Other foods to avoid include salt and artificial additives, such as preservatives. Choose fresh, unprocessed foods whenever possible.

Exercise

The physical symptoms of anxiety are caused by the ‘flight-or-fight’ response, which floods the body with adrenaline and other stress chemicals. Exercise burns up stress chemicals and promotes relaxation. Physical activity is another helpful way to manage anxiety. Aim to do some physical activity at least three to four times every week, and vary your activities to avoid boredom.

Learning to be assertive

Being assertive means communicating your needs, wants, feelings, beliefs and opinions to others in a direct and honest manner without intentionally hurting anyone’s feelings. A person with an anxiety disorder may have trouble being assertive because they are afraid of conflict or believe they have no right to speak up. However, relating passively to others lowers self-confidence and reinforces anxiety. Learning to behave assertively is central to developing a stronger self-esteem.

Building self-esteem

People with anxiety disorder often have low self-esteem. Feeling worthless can make the anxiety worse in many ways. It can trigger a passive style of interacting with others and foster a fear of being judged harshly. Low self-esteem may also be related to the impact of the anxiety disorder on your life. These problems may include:

- Isolation

- feelings of shame and guilt

- depressed mood

- difficulties in functioning at school, work or in social situations.

The good news is you can take steps to learn about and improve your self-esteem. Community support organisations and counselling may help you to cope with these problems.

Structured problem solving

Some people with anxiety disorders are ‘worriers’, who fret about a problem rather than actively solve it. Learning how to break down a problem into its various components – and then decide on a course of action – is a valuable skill that can help manage generalised anxiety and depression. This is known as structured problem solving.

Medication

It is important that medications are seen as a short-term measure, rather than the solution to anxiety

Research studies have shown that psychological therapies, such as cognitive behaviour therapy, are much more effective than medications in managing anxiety disorders in the long term. Your doctor may prescribe a brief course of tranquillisers or antidepressants to help you deal with your symptoms while other treatment options are given a chance to take effect.

Support groups and education

Support groups allow people with anxiety to meet in comfort and safety, and give and receive support. They also provide the opportunity to learn more about anxiety and to develop social networks.

Etiology:

The etiology of anxiety may include stress, physical condition such as diabetes or other comorbidities such as depression, genetic, first-degree relatives with generalized anxiety disorder (25%), environmental factors, such as child abuse, and substance abuse. The anxiety disorders are so heterogeneous that the relative roles of these factors are likely to differ. Some anxiety disorders, like panic disorder, appear to have a stronger genetic basis than others (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 1998), although actual genes have not been identified. Other anxiety disorders are more rooted in stressful life events. It is not clear why females have higher rates than males of most anxiety disorders, although some theories have suggested a role for the gonadal steroids. Other research on women’s responses to stress also suggests that women experience a wider range of life events as stressful as compared with men who react to a more limited range of stressful events, specifically those affecting themselves or close family members. What the myriad of anxiety disorders have in common is a state of increased arousal or fear. Anxiety disorders often are conceptualized as an abnormal or exaggerated version of arousal. Much is known about arousal because of decades of study in animals and humans of the so-called “fight-or-flight response,” which also is referred to as the acute stress response. The acute stress response is critical to understanding the normal response to stressors and has galvanized research, but its limitations for understanding anxiety have come to the forefront in recent years (Barbee, 1998). In common parlance, the term “stress” refers either to the external stressor, which can be physical or psychosocial in nature, as well as to the internal response to the stressor. Yet researchers distinguish the two, calling the stressor the stimulus and the body’s reaction the stress response. This is an important distinction because in many anxiety states there is no immediate external stressor. The following paragraphs describe the biology of the acute stress response, as well as its limitations, in understanding human anxiety. Emerging views about the neurobiology of anxiety, attempt to integrate and understand psychosocial views of anxiety and behavior in relation to the structure and function of the central and peripheral nervous system. There are several major psychological theories of anxiety: psychoanalytic and psychodynamic theory, behavioral theories, and cognitive theories. Psychodynamic theories have focused on symptoms as an expression of underlying conflicts. Although there are no empirical studies to support these psychodynamic theories, they are amenable to scientific study and some therapists find them useful. For example, ritualistic compulsive behavior can be viewed as a result of a specific defense mechanism that serves to channel psychic energy away from conflicted or forbidden impulses. Phobic behaviors similarly have been viewed as a result of the defense mechanism of displacement. From the psychodynamic perspective, anxiety usually reflects more basic, unresolved conflicts in intimate relationships or expression of anger. More recent behavioral theories have emphasized the importance of two types of learning: classical conditioning and vicarious or observational learning. These theories have some empirical evidence to support them. In classical conditioning, a neutral stimulus acquires the ability to elicit a fear response after repeated pairings with a frightening (unconditioned) stimulus. In vicarious learning, fearful behavior is acquired by observing others’ reactions to fear-inducing stimuli. With general anxiety disorder, unpredictable positive and negative reinforcement is seen as leading to anxiety, especially because the person is unsure about whether avoidance behaviors are effective. Cognitive factors, especially the way people interpret or think about stressful events, play a critical role in the etiology of anxiety. A decisive factor is the individual’s perception, which can intensify or dampen the response. One of the most salient negative cognitions in anxiety is the sense of uncontrollability. It is typified by a state of helplessness due to a perceived inability to predict, control, or obtain desired results. Negative cognitions are frequently found in individuals with anxiety. Many modern psychological models of anxiety incorporate the role of individual vulnerability, which includes both genetic and acquired predispositions. There is evidence that women may ruminate more about distressing life events compared with men, suggesting that a cognitive risk factor may predispose them to higher rates of anxiety and depression.

Biological – Genetic influences. While genetics have been known to contribute to the presentation of anxiety symptoms, the interaction between genetics and stressful environmental influences appears to account for more anxiety disorders than genetics alone (Bienvenu, Davydow, & Kendler, 2011). The quest to identify specific genes that may predispose individuals to develop anxiety disorders has led researchers to the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR). Mutation of the 5-HTTLPR gene is related to a reduction in serotonin activity and an increase in anxiety-related personality traits (Munafo, Brown, & Hairiri, 2008).

Biological – Neurobiological structures. Researchers have identified several brain structures and pathways that are likely responsible for anxiety responses. Among those structures is the amygdala, the area of the brain that is responsible for storing memories related to emotional events (Gorman, Kent, Sullivan, & Coplan, 2000). When presented with a fearful situation, the amygdala initiates a reaction to ready the body for a response. First, the amygdala triggers the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis to prepare for immediate action— either to fight or flight. The second pathway is activated by the feared stimulus itself, by sending a sensory signal to the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, to determine if the threat is real or imagined. If it is determined that no threat is present, the amygdala sends a calming response to the HPA axis, thus reducing the level of fear. If a threat is present, the amygdala is activated, producing a fear response.

Specific to panic disorder is the implication of the locus coeruleus, the brain structure that serves as an “on-off” switch for norepinephrine neurotransmitters. It is believed that increased activation of the locus coeruleus results in panic-like symptoms; therefore, individuals with panic disorder may have a hyperactive locus coeruleus, leaving them more susceptible to experience more intense and frequent physiological arousal than the general public (Gorman, Kent, Sullivan, & Coplan, 2000). This theory is supported by studies in which individuals experienced increased panic symptoms following the injection of norepinephrine (Bourin, Malinge, & Guitton, 1995). Unfortunately, norepinephrine and the locus coeruleus fail to fully explain the development of panic disorder, as treatment would be much easier if only norepinephrine was implicated. Therefore, researchers argue that a more complex neuropathway is likely responsible for the development of panic disorder. More specifically, the corticostriatal-thalamocortical (CSTC)circuit, also known as the fear-specific circuit, is theorized as a major contributor to panic symptoms (Gutman, Gorman, & Hirsch, 2004). When an individual is presented with a frightening object or situation, the amygdala is activated, sending a fear response to the anterior cingulate cortex and the orbitofrontal cortex. Additional projection from the amygdala to the hypothalamus activates endocrinologic responses to fear, releasing adrenaline and cortisol to help prepare the body to fight or flight (Gutman, Gorman, & Hirsch, 2004). This complex pathway supports the theory that panic disorder is mediated by several neuroanatomical structures and their associated neurotransmitters.

Psychological

Psychological – Cognitive. The cognitive perspective on the development of anxiety related disorders centers around dysfunctional thought patterns. As seen in depression, maladaptive assumptions are routinely observed in individuals with anxiety-related disorders, as they often engage in interpreting events as dangerous or overreacting to potentially stressful events, which contributes to an overall heightened anxiety level. These negative appraisals, in combination with a biological predisposition to anxiety, likely contribute to the development of anxiety symptoms. Sensitivity to physiological arousal not only contributes to anxiety disorders in general, but also for panic disorder where individuals experience various physiological sensations and misinterpret them as catastrophic. One explanation for this theory is that individuals with panic disorder are more susceptible to more frequent and intensive physiological symptoms than the general public. Others argue that these individuals have had more trauma-related experiences in the past, and therefore, are quick to misevaluate their symptoms as a potential threat. This misevaluation of symptoms as impending disaster likely maintain symptoms as the cognitive misinterpretations to physiological arousal creates a negative feedback loop, leading to more physiological changes.

Social anxiety is also primarily explained by cognitive theorists. Individuals with social anxiety disorder tend to hold unattainable or extremely high social beliefs and expectations. Furthermore, they often engage in preconceived maladaptive assumptions that they will behave incompetently in social situations and that their behaviors will lead to terrible consequences. Because of these beliefs, they anticipate social disasters will occur and, therefore, avoid social encounters (or limit them to close friends/family members) in efforts to prevent the disaster (Moscovitch et al., 2013). Unfortunately, these cognitive appraisals are not only isolated to before and during the event. Individuals with social anxiety disorder will also evaluate the social event after it has taken place, often obsessively reviewing the details. This overestimation of social performance negatively reinforces future avoidance of social situations.

Psychological – Behavioral. The behavioral explanation for the development of anxiety disorders is mainly reserved for phobias—both specific and social phobia. More precisely, behavioral theorists focus on respondent conditioning – when two events that occur close together become strongly associated with one another, despite their lack of causal relationship (see Module 2 for an explanation of respondent conditioning). infamous Little Albert experiment is an example of how respondent conditioning can be used to induce fear through associations. In this study, Little Albert developed a fear of white rats by pairing a white rat with a loud sound. This experiment, although lacking ethical standards, was groundbreaking in the development of learned behaviors. Over time, researchers have been able to replicate these findings (in more ethically sound ways) to provide further evidence of the role of respondent conditioning in the development of phobias.

Psychological – Modeling is another behavioral explanation of the development of specific and social phobias. In modeling, an individual acquires a fear though observation and imitation (Bandura & Rosenthal, 1966). For example, when a young child observes their parent display irrational fear of an animal, the child may then begin to display similar behavior. Similarly, seeing another individual being ridiculed in a social setting may increase the chances of developing social anxiety, as the individual may become fearful that they would experience a similar situation in the future. It is speculated that the maintenance of these phobias is due to the avoidance of the feared item or social setting, thus preventing the individual from learning that the object or situation is not something that should be feared. While modeling and respondent conditioning largely explain the development of phobias, there is some speculation that the accumulation of many these learned fears will develop into generalized anxiety disorder. Through stimulus generalization, or the tendency for the conditioned stimulus to evoke similar responses to other stimuli, a fear of one stimulus (such as the dog) may become generalized to other items (such as all animals). As these fears begin to grow, a more generalized anxiety will present, as opposed to a specific phobia.

Sociocultural

Seeing how prominent the biological and psychological constructs are in explaining the development of anxiety-related disorders, we also need to review the social constructs that contribute and maintain anxiety disorders. While characteristics such as living in poverty, experiencing significant daily stressors, and increased exposure to traumatic events are all identified as significant contributors to anxiety disorders, additional sociocultural influences such as gender and discrimination have also received considerable attention, mainly due to the epidemiological nature of the disorder. Gender has largely been researched within anxiety disorders due to the consistent discrepancy in the diagnosis rate between men and women. As previously discussed, women are routinely diagnosed with anxiety disorders more often than men, a trend that is observed throughout the entire lifespan. One potential explanation for this discrepancy is the influence of social pressures on women. Women are more susceptible to experience traumatic experiences throughout their life, which may contribute to anxious appraisals of future events. Furthermore, women are more likely to use emotion-focused coping, which is less effective in reducing distress than problem- focused coping (McLean & Anderson, 2009). These factors may increase levels of stress hormones within women that leave them susceptible to develop symptoms of anxiety. Therefore, it appears a combination of genetic, environmental, and social factors may explain why women tend to be diagnosed more often with anxiety-related disorders.

Risk Factors:

These factors may increase your risk of developing an anxiety disorder:

-

- Trauma. Children who endured abuse or trauma or witnessed traumatic events are at higher risk of developing an anxiety disorder at some point in life. Adults who experience a traumatic event also can develop anxiety disorders.

- Stress due to an illness. Having a health condition or serious illness can cause significant worry about issues such as your treatment and your future.

- Stress buildup. A big event or a buildup of smaller stressful life situations may trigger excessive anxiety — for example, a death in the family, work stress or ongoing worry about finances.

- Personality. People with certain personality types are more prone to anxiety disorders than others are.

- Other mental health disorders. People with other mental health disorders, such as depression, often also have an anxiety disorder.

- Having blood relatives with an anxiety disorder. Anxiety disorders can run in families.

- Drugs or alcohol. Drug or alcohol use or misuse or withdrawal can cause or worsen anxiety.

Complications

Having an anxiety disorder does more than make you worry. It can also lead to, or worsen, other mental and physical conditions, such as:

- Depression (which often occurs with an anxiety disorder) or other mental health disorders

- Substance misuse

- Trouble sleeping (insomnia)

- Digestive or bowel problems

- Headaches and chronic pain

- Social isolation

- Problems functioning at school or work

- Poor quality of life

Management:

PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMET

Treatment (Medication)

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

The widely studied SSRIs, and to a growing degree, the SNRIs (and for obsessive–compulsive disorder [OCD] the mixed noradrenergic and serotonergic reuptake inhibitor tricyclic clomipramine), are considered the first-line pharmacological treatments for anxiety disorders

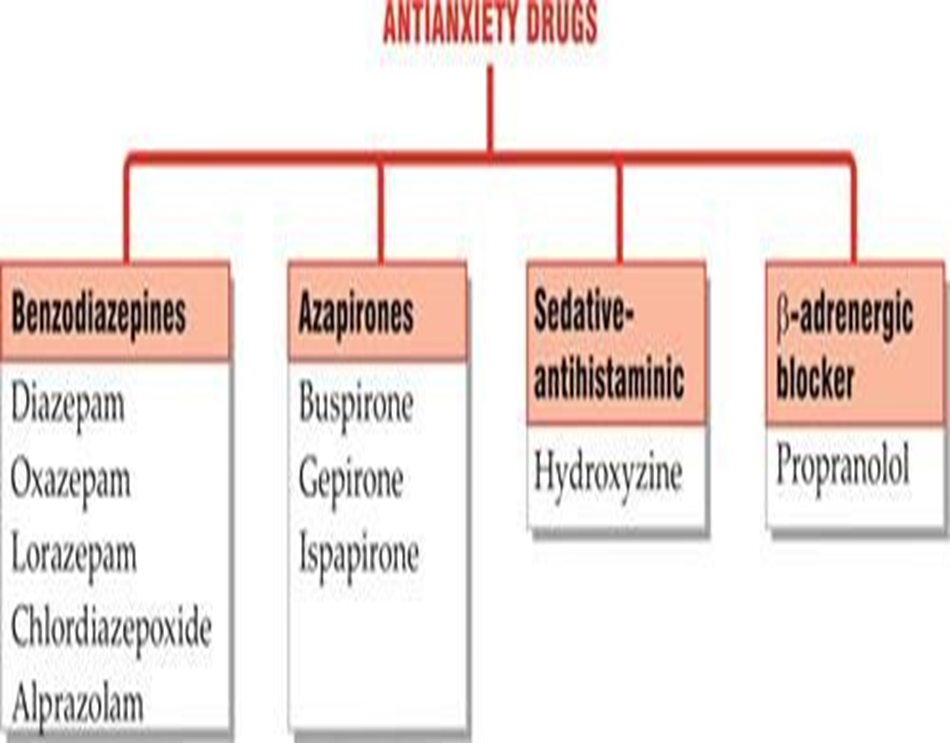

- Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines bind to a specific receptor site on the gamma-aminobutyric acid–A receptor (GABA–A) complex and facilitate GABA inhibitory effects by acting on a chloride ion channel. They were initially considered first-line treatments for anxiety because of their tolerability and equal efficacy to TCAs, but became second-line options when it became clear that SSRIs were both more tolerable and efficacious. Currently, benzodiazepines are primarily used for individuals who have had suboptimal responses to antidepressants

- Alpha–delta calcium channel anticonvulsants

The alpha–delta calcium channel class of anticonvulsants, including both gabapentin and the newer agent pregabalin, widely reduce neuronal excitability and resemble the benzodiazepines in their ability to alter the balance between inhibitory and excitatory neuronal activity. Also similar to benzodiazepines, these drugs have a rapid onset of action and are superior to placebo in GAD and SAD.

Beta blockers and azapirones

Beta blockers and azapirones have even fewer uses. Beta blockers have been prescribed as single- dose agents for performance-related anxiety (e.g., musician at a critical audition; because they can reduce the peripheral physical symptoms (e.g., palpitations and hands trembling) of anxiety within 30–60 min; however, they do not affect the cognitive and emotional symptoms of anxiety.

Azapirones bind to the 5-HT1A receptor and are thought to alter control of the firing rate of serotonin neurons. They typically take 2–4 weeks to take effect, are generally well tolerated, and lack the dependence issues of the benzodiazepines. However, GAD is the only anxiety disorder in which the azapirones have consistently demonstrated efficacy. Because GAD often includes a depression component, antidepressant medications are the more logical treatment choice.

Non-Pharmacological Management

- Sleep Hygiene

- Meditation

- Exercise

- Good Nutrition

Drug Used In Anxiety Disorder:

Vivek Shelar *

Vivek Shelar *

Dr Ajay Kale

Dr Ajay Kale

10.5281/zenodo.13292882

10.5281/zenodo.13292882